Karol Broniatowski - Gouache paintings

Mediathek Sorted

Trauma and Fate

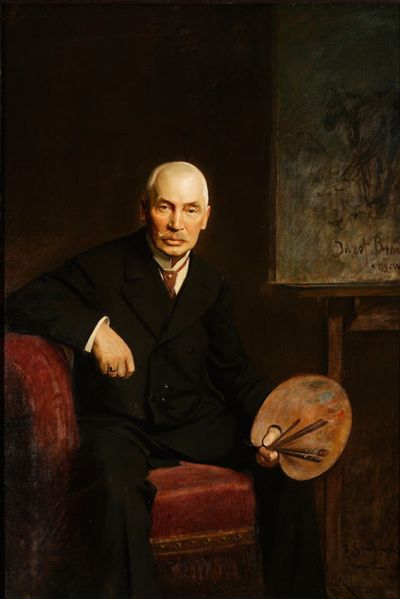

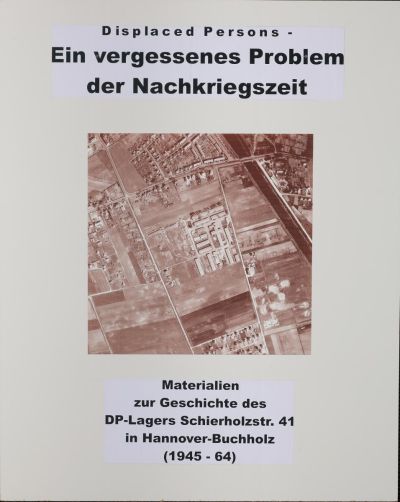

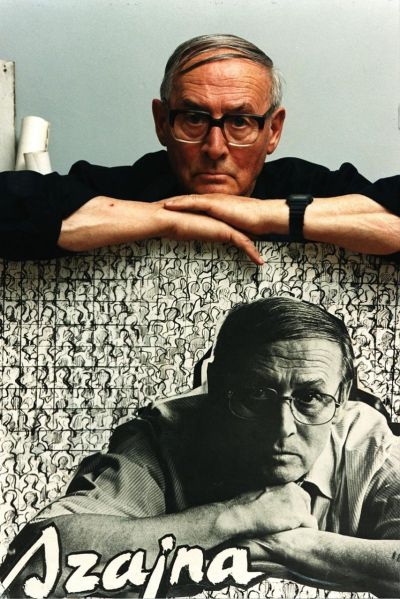

Karol Broniatowski presented his graduation exhibition in 1970. It consisted of dozens of life-size human figures caught in motion running across the ground and “levitating“ in space. They were made from newspapers and hardened with transparent resin that allowed the viewers to see fragments of the illustrations, texts and headlines. Both the material and the technique of revealing the hardened scraps of information beneath the layer of polyester remind us of the late sculptural work of Alina Szapocznikow (1926-1973), who was one generation older: more precisely her series Memories and Tumours (Pamiątki i tumory), and her comprehensive panneaus, Alina’s Burial (Pogrzeb Aliny), which were the sick artist’s final farewell from the world, and the first and only time in her work that she referred directly to her memories of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. She completed the works in Paris after her last visit to Poland, where she witnessed the anti-Semitic agitation that flared up after the somewhat harmless student demonstrations in March 1968. In the same period (1969-1972) Broniatowski was creating his “running” figures that were exhibited in 1972 in the Polish pavilion at the Venice Biennale under the title Threat (Zagrożenie). Their appearance and shape differ from Szapocznikow’s works, but all the same their terrifying message was a play on the Memento of the outstanding post-war sculptor.

The second feature that allows us to compare Broniatowski’s work with Szapocznikow’s practice was the focusing of attention on the category of fleshiness, a concept which is expressed by separate words in many different European languages. This is not about body but flesh; not le corpus but la chair, not Körper but Fleisch, something that emphasises the biological side of life. This aspect appeared in the artist’s practice only after many years of measuring himself against the conceptual dimension of sculptural creation, when he tackled the shape of works like Big Man. This work consisted of piles of newspapers cut into the desired format and consisting of 93 sections. It was impossible to show it in full and it had something to do with Joseph Beuys’ social sculptures. After he moved to Berlin Broniatowski decided to replace the material with bronze, thereby altering the fleshiness of his art. The straight cut pile of newspapers and the concepts of “amount”, “opportuneness” and “innumerability” it contained, suddenly changed into a heaving, but substantially homogenous form that also remained concrete even when it only revealed a small fragment of the figure on show; a figure that appeared to be only somewhat less infused with eroticism than the parts of the body emphasised by Szapocznikow.

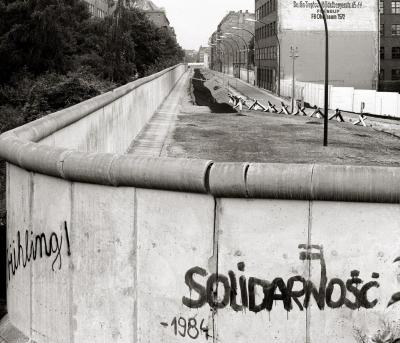

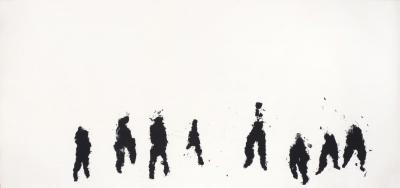

In this way the several elements contained in Big Man were transformed into a group of 93 “Small Pacers”[1] cast in bronze, whose expression was a direct link to the resin figures made during the first period of Broniatowski’s career. But now the sculptural expression had taken on other properties. His thoughts on the various possibilities of interpreting the concept of “figure” in sculpture led him to experimenting with a subsequent concept, that of “silhouette”. It was all about filling out the three-dimensional material of something that was perceived from afar as being a flat form: hence it was about giving it a certain fleshiness and therefore more weight. That said the small silhouettes gives the impression of being frozen in an incomplete gesture as sometimes happens in dreams where we seem to be flying although our feet are stuck fast to the ground. This was no longer a conceptually social sculpture but a grappling with a persecuted community.

[1] Kleine Schreitende, 1985

In this respect another work gives us a much stronger statement. The feeling of terror that is linked with the consciousness of the irreversibility of fate is expressed in the memorial he created at Grunewald station.[2] It resulted from an unexpected approach to his sculptural work based on his desire to create a “figure” and simultaneously to endow it with a suggestion of non-fleshiness. Given these preconditions the artist succeeded in creating a reverse perspective of time by grasping human shapes in the manner of a negative photo. The 20 metre long wall of hollow silhouettes literally disappear into thin air, lose their weight and fleshiness like people who become their own shadows as soon as they find themselves on the ramp.

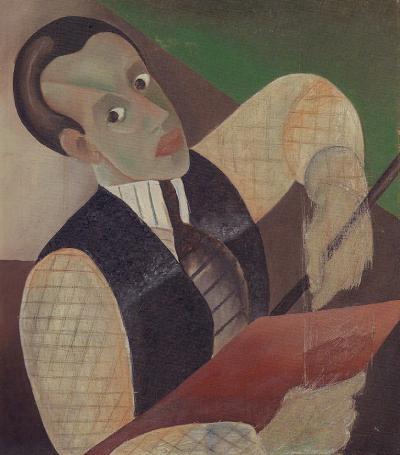

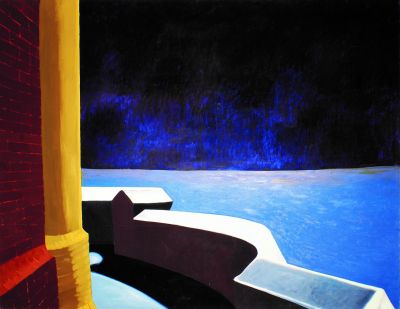

Drawings and sketches were part of the work on the memorial: at sometime or other they were liberated from their helpful function and changed into an ordered series. Almost all of them portray human silhouettes drawn with Indian ink on huge cardboard boxes, which are reminiscent of the hollowed out negative figures in the wall of the memorial and remind us in the conventional sense rather of positive photographic prints. For this reason we perceive them in the categories of the dialectic of spirit and fleshiness, memory and oblivion, life and death. In the course of time however, the material began to thicken and take on juiciness and colours. Alongside the clearly eschatological threads there also emerges a reflection on the past, about art and culture, what remains of people. The series of gouache paintings is a clear link to ancient classical culture; the centaur, a symbol of vitality and potency resulting from the unification of human and animal features, i.e. from purely biological characteristics. Portraits of animals in Palaeolithic rock paintings in the caves of Western Europe have a similar expression. In Broniatowski’s works the subtle links with the earliest period of creative activities are expressed not only in the mythological figure of the centaur but also in his use of a rusty red reminiscent of the natural pigments that were used in Altamira, Lascaux and Gragas. The “rudimentary“, fuzzy outlines of the silhouettes painted in red look like excerpts of living bodies reminiscent not only of the hand-painted portraits in Altamira and Gargas but also of the ultramarine blue silhouettes in the pictures of Yves Klein, which are type of modern Vera Icon, a portrait of real registered fleshiness caught in motion on the canvas. This is nothing other than an attempt to capture an accidental momentum, to pin down a fleeting “flesh” situation that is simultaneously subject to change. The consciousness of impermanence also arises when we are faced with the female coquetry indicating the category of vanitas, that can be found in European art over the past thousand years.

The drawings and gouache paintings are therefore a natural and inalienable complement to Karol Broniatowski’s sculptural work. Only thanks to them can we see his creative path – from his debut to the present day – as a logical, unbroken whole. It is not simply based on reflections on form and the way in which figures function in art, but is above all a grappling with the crumbly nature of human flesh resulting from the war trauma his generation inherited from their parents.

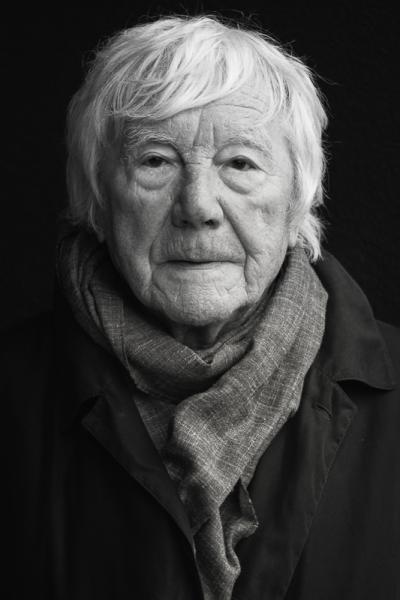

Anda Rottenberg, November 2017

[2] „Mahnmal für die deportierten Juden Berlins am Bahnhof Grunewald“, 1991.