Maczków. A Polish enclave in North Germany

Mediathek Sorted

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Maczków. Polnische Enklave in Norddeutschland - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

Paradies auf Zeit - wie aus Haren Maczków wurde

Poles in Emsland

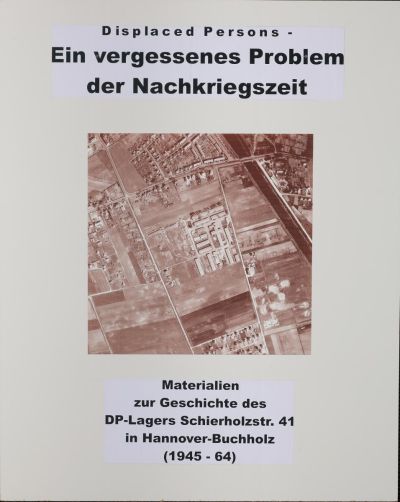

The north-western part of Germany, known as the Emsland, was captured by Stanisław Maczek's First Tank Division, and after the war ended the region was allotted to the British occupation zone. Since the area was under Polish administration for a while, it was also known as the "Polish Occupation Zone in Germany". It extended over 6,500 square kilometres to include the districts of Aschendorf, Meppen and Lingen as well as the counties of Bentheim, Bensbrück and Cloppenburg with all their villages.

Thousands of Poles, most of whom were liberated from concentration camps and POW camps, were living in the area occupied by General Maczek and his troops. Another large group consisted of former forced labourers. The Poles soon referred to these people as "dipisi", a nickname derived from the abbreviation of the English term "Displaced Persons" (DPs), the term used by aid organisations and the occupying powers in Germany. The first definition of the term in November 1944 was that of:

"... civilians who are outside their state for reasons of war; those who want to return or find a new home but are unable to do so without outside help" (Lembeck, p. 38).

In mid-May 1945, General Henry Crerar, commander of the Second Canadian Corps (at whose side the First Polish Tank Division had fought, suggested to the commander-in-chief of the British occupying forces, Gen. Bernard Montgomery, the idea of setting up a Polish enclave in a part of the Emsland. Montgomery accepted this proposal and the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchil, gave the order to establish an occupation corps of Polish soldiers.

According to estimates by the Polish historian Jan Rydel, around 40,000 DPs and prisoners of war from various nations were present in Emsland in August 1945. That said, after the Russian prisoners of war and the interned Italian soldiers had returned home the majority of these were Polish. In November 1945, the proportion of foreigners in Lower Saxony, to which the Emsland belonged, is said to have been around 6%.

The conglomeration of thousands of people, who were often in a wretched state of health and had great material needs, caused many problems. To make room for the newcomers, the houses belonging to the Germans were vacated. In Emsland, these measures were initiated on 19. May 1945, when the mayor of Haren, Hermann Wichers, received the order to evacuate his town.

The evacuation of the town of Haren

Around 3,500 inhabitants were expected to leave the town by May 28th1945. They were told that they were not allowed to return under any circumstances. Special permits were to be issued for transit purposes. The German evacuees were distributed among 30 neighbouring communities. Only the mayor and his family and the nuns who were part of the Polish health care system in the St. Francis Church were allowed to stay in the town. The mayor remained responsible for maintaining the German administration and for the affairs of the citizens of Haren who had been sent to the neighbouring localities. He issued permits and provided them with the basic necessities. The chronicle of the town announced that a "black day" had arrived for Haren. Later it was referred to as the "Polish period". But things looked completely different from the point of view of those who found a a temporary home here after years of war, oppression and homelessness.

In 1988 General Maczekrecalled:"The British administration in the occupied area was surprised by the masses of Poles arriving from the concentration camps, internment camps and forced labour camps. It evacuated the town of Haren, known to them from the battles fought here by my division, and handed it over to me to dispose of as I thought best. For some years afterwards a purely Polish town with a Polish population and Polish administrative authorities was established in western Germany. (...) Thousands of Polish men and women settled in the town and used it as temporary refuge before scattering all over the world."

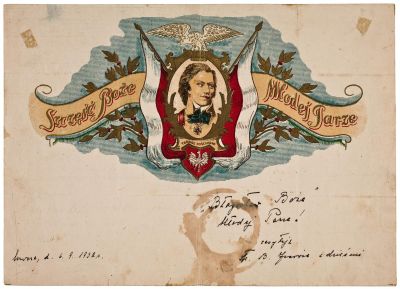

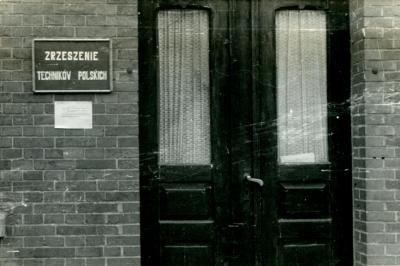

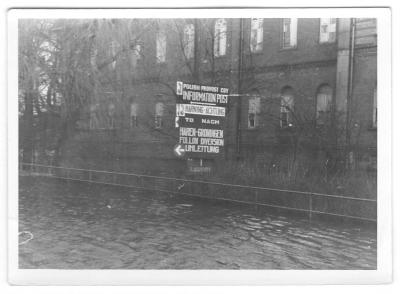

Haren becomes Maczków

Initially the Polonised town of Haren was christened Lwów (now Lviv), but only a few weeks later, on 24thJune 1945, it was renamed Maczków, as the British considered the earlier name too provocative in view of their ally, the USSR. During this period, heightened tensions and direct confrontations among the Allies were still avoided. Whatever the case, the new designationn named in honour of the commander of the First Division did not cause any controversy. The town was given its new name in the presence of General Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski, who happened to be on a visit at the time. The streets and squares were also renamed: Armii Krajowej, Legionów, Jagiellońska, Lwowska and Łyczakowska. Nor did the reference to the lost Polish eastern territories trigger any protest.

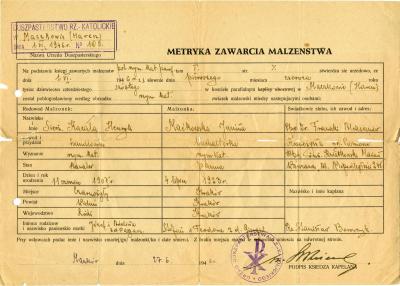

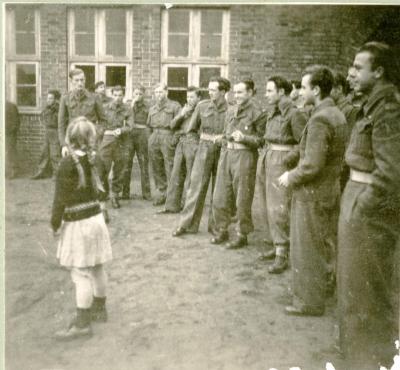

Approximately 5,000 Poles were living in Maczków in June 1945. Most of these were young people who had been freed from the concentration camps and prison camps. They also included people who had participated in the Warsaw Uprising, including over 1,700 young women from Stalag VI C in Oberlangen. All of them wanted to start a more or less normal life after their wartime years in captivity, forced labour and homelessness. But the young also insisted on their own rights: some of them got married and had children. Indeed, between 1945 and 1948, 289 marriages took place in Maczków, and 497 births and 101 funerals were registered in Maczków.

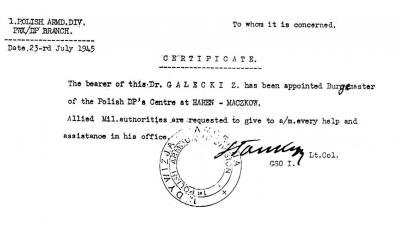

The Polish Administration

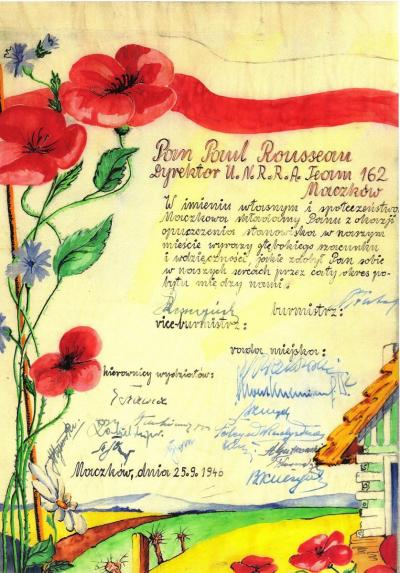

The establishment of an administrative structure was of fundamental importance for the organisation of life in the Polish community. As a result, a mayor and a twelve-member town council were elected. The first incumbent was Zygmunt Gałecki. His successor was Mieczysław Futa. In addition, the town was given a new official seal with a fresh coat of arms showing the standard of the First Armoured Division: a poppy, a steel helmet and a hussar's wing.

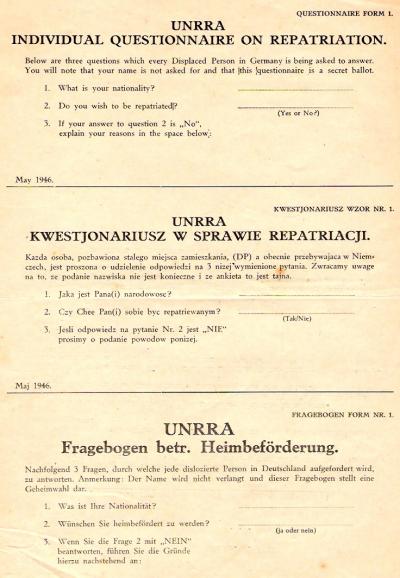

One of the main tasks of the city administration was the allocation of food, goods and accommodation. A police force and fire brigade were reestablished and canteens were also set up. This was necessary in view of the many people who had been left on their own and the problems with resources. Food supplies were initially in the hands of the military authorities and were later transferred to aid organisations like UNRRA (the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency) and IRO (the International Refugee Organisation).

Culture

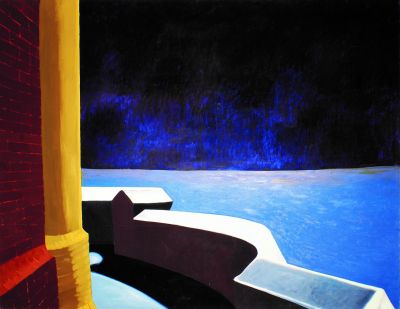

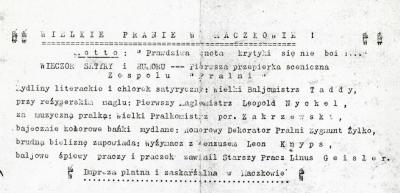

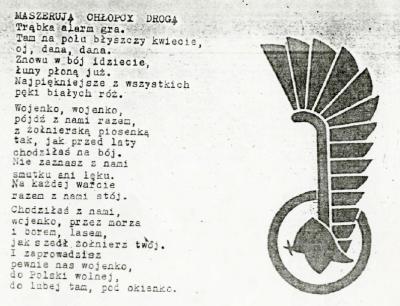

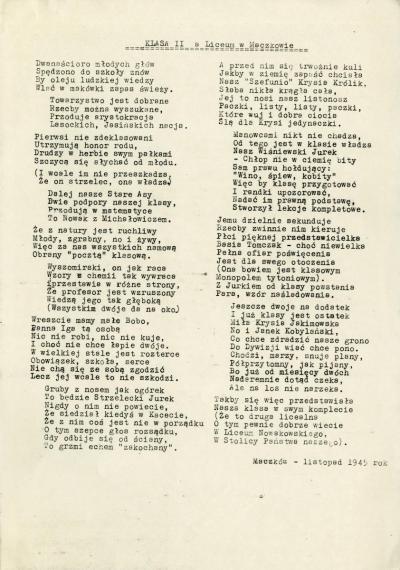

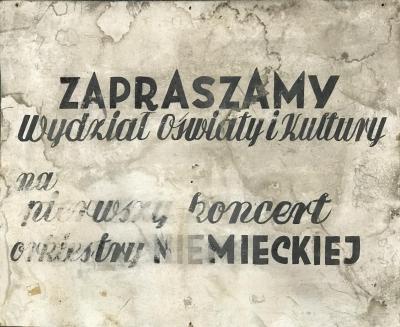

Maczków had a flourishing cultural life. There was the Wojciech-Bogusławski Folk Theatre (Teatr Ludowy im. Wojciecha Bogusławskiego) and the puppet theatre, “Kukiełki Maczkowskie“ (the Maczkow Marionettes). In January 1946 both companies staged four plays. The satirical show "Big Laundry", which focused on everyday life in the now Polish town, proved very popular. The residents enjoyed these shows and the theatre with its 300 seats was always sold out.

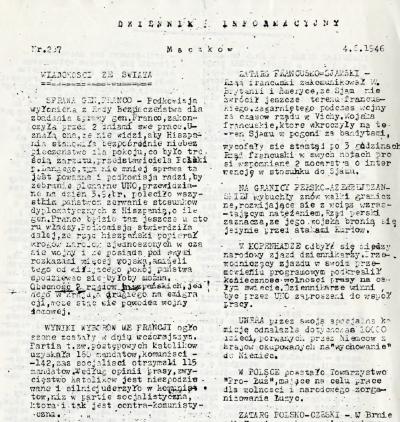

Likewise, press publications issued by the DPs and the Polish Division were read very carefully. In Maczków. These included the newspaper "Biuletyn" (The Bulletin), the "Dziennik Żołnierza 1. Dywizji Pancernej" (The Soldier's Day Gazette of the First Tank Division) and "Defilada. Tygodnik Polskich Sił Zbrojnych w Niemczech" (The Parade. The Weekly Journal of the Polish Armed Forces in Germany). The latter two publications had a total circulation of 90,000 until the Division was transferred to Great Britain in May 1947. The Warsaw magazine "Repatriant" (The Homecomer) was also published in the town, but it was not well received in Maczków, because its propaganda calling for a return to Poland was too blatant and information about living conditions in Poland was too sketchy and uncertain.

The town also had a cinema, a library with a reading room and some cultural rooms. The dance halls, where people could amuse themselves three times a week to the sounds of a specially created orchestra, enjoyed great popularity.

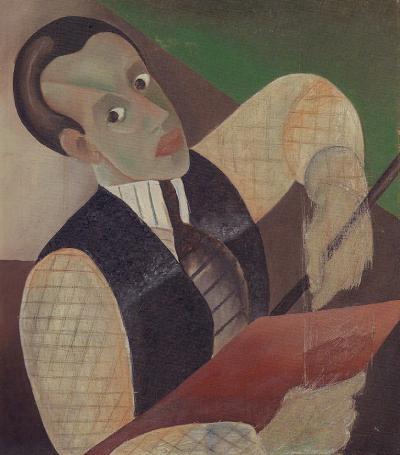

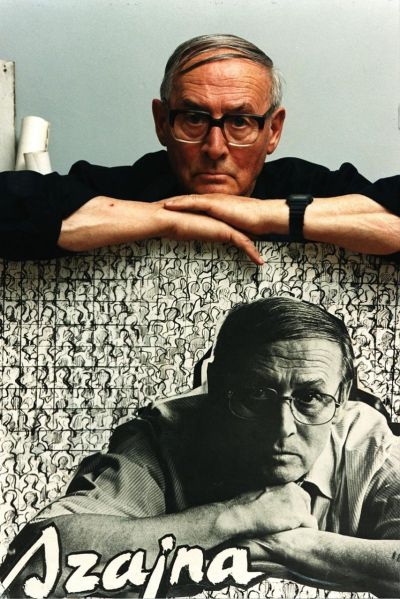

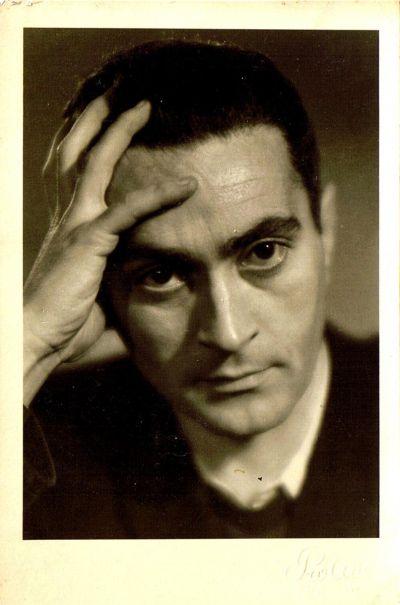

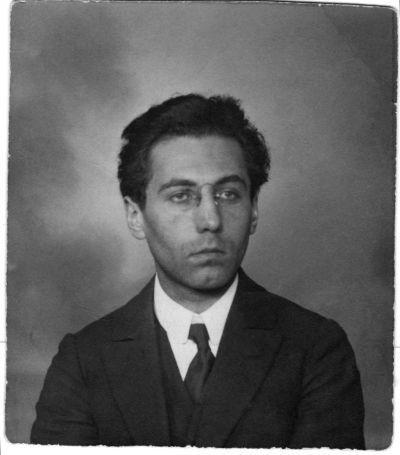

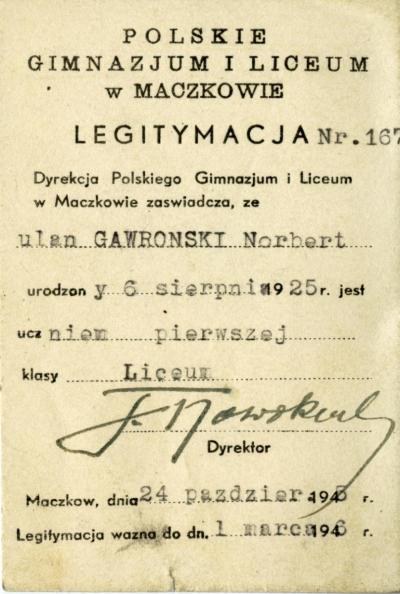

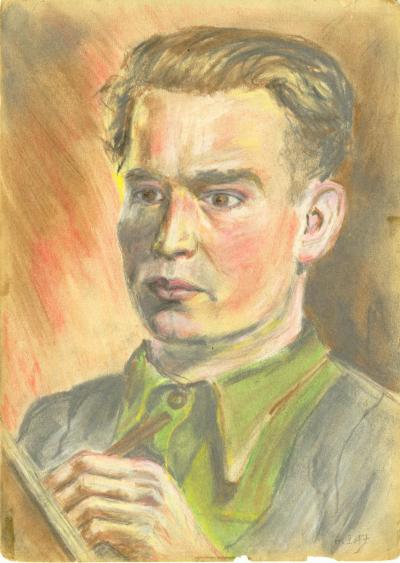

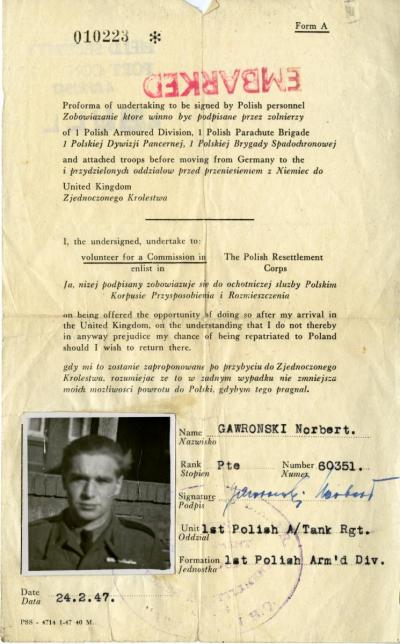

Maczków was also regularly visited by performers mediated by the Polish department of the YMCA and the I. Tank Division. There was a wide variety of repertoire, from musicals to ballet evenings to cabaret. The citizens of the town also had the opportunity to listen to recitations by the poet Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński. A well-known director, León Schiller supported the construction of the theatre. There was even a circus in the town. Maczków was also the home of young artists who gained great fame after returning to Poland or emigrating to other countries. These included people like Józef Szajna, a leading representative of Polish art and theatre, and the famous architect Norbert Gawroński, who later worked in Amsterdam.

The school system

After the end of the war many people wished to complete their schooling or continue their education. Many of them even came into contact with a school for the first time. The general view was that education would help people find better paid work. But the necessary measures received insufficient and precarious support from the British occupying forces, UNRRA and the First Tank Division.

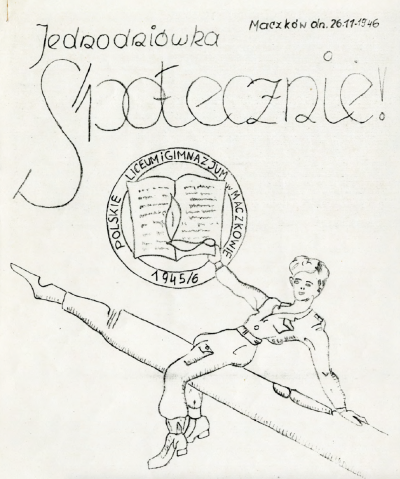

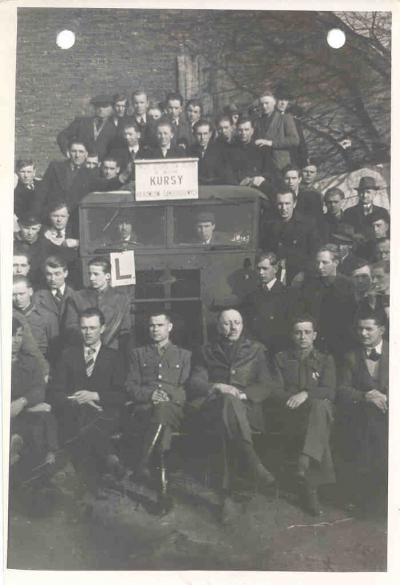

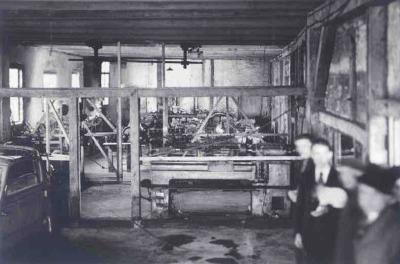

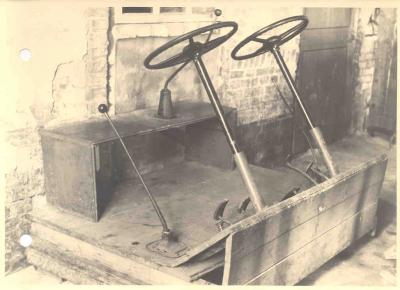

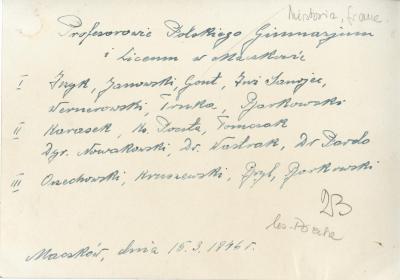

In this spirit, kindergartens, two primary schools, a secondary school, a lyceum, the vocational school "Polskie Gimnazjum Mechaniczne" (The Polish High School for Mechanics) and an adult education centre were quickly established in Maczków. Tadeusz Nowakowski was appointed headmaster of the secondary school and the lyceum. The teaching staff included another man called Tadeusz Nowakowski, who later became well-known in exile as the author of the novel "Obóz wszystkich świętych“, which was published in Paris in 1957 and dealt with Maczków. The German edition of the novel was published in Cologne in 1960 under the title "Polonaise Allerheiligen". The first parts of the manuscript were set down by Nowakowski in a class register he had found at the school in Maczków.

There were 350 children in the primary school in Maczków and 268 in the secondary school and lyceum. The syllabus included the humanities and natural sciences. Alongside Polish, history, geography, chemistry, mathematics and religion were also taught. Attendance at the secondary school and the lyceum ended with the Abitur (A-levels).

The educational standards in Maczków were so high that the secondary school and lyceum also attracted students from outside. Since the high school had boarding facilities for girls and boys, applicants came from all over Germany. A-level qualifications from Maczków were regarded as the entrance ticket to universities in Germany and other European countries. That said, It was no easy matter to transform into an eager student after the many tragic experiences during the war.

"We wanted to learn and make up for the years lost in the war”, recalled Józef Szajna (Maczków, 1947), a respected artist and former prisoner of the Auschwitz concentration camp. I wasn't a good student. “It took me four hours to finish what others did in 40 minutes. Complexes arose within me and my self-confidence suffered. It was as if my long stay in a concentration camp had erased my concentration and discipline (...). The school building still exists. Our teachers were former prisoners of war from the officers' camps. Most of them came from the Murnau Oflag and had been teachers before the war. The demands were high and the level of the students very different. Even though the church was very large and we attended Holy Mass every Sunday, we could not count on God's help. The soldiers who had grown up during the war, the partisans and the female participants in the Warsaw Uprising faced the exams with fear (...)"(quoted in Lembeck, p. 102).

The adult education centre aroused great interest among the DPs. A total of 150 people attended the courses in history, geography, technology and other subjects. Foreign languages were very much in demand, especially English, as a command of English could be useful when emigrating. English was taught by two teachers whose courses were attended by 200 DPs.

As time went by, the Emsland became a centre of Polish education in Germany. Maczków was the headquarters of the Third School District, whose supervisory authority was headed by Szczepan Zimmerer. He determined the curricula together with the regional school authorities.

Following the return of DPs to their homes and emigration to other Western countries pupil numbers decreased and the schools were gradually closed. School operations were finally discontinued at the turn of 1949.

Religious life

Religious life soon developed as a result of the work of Polish clergymen. Maczków was home to the largest Roman Catholic parish in the DP community, and four Polish Catholic priests worked here (the other parishes usually had only one priest). Their duties consisted of two of the clergy celebrating Holy Mass and divine services, giving the Holy Sacraments during religious instruction in the schools attended by the DPs and leading the Sunday School. The fourth provided welfare and pastoral care for the people who were often severely afflicted by their fate.

Work

A major problem for DPs was the lack of employment, especially as they were not allowed to work for German companies. As a result the only places of work were in the DP camps or with the Allied forces, but there were not too many opportunites available here either. Most working people therefore found something to keep themselves busy in the camps, where they did a variety of tasks ranging from administrative duties to garbage collection. Only 10 to 15% of the people in the Emsland were employed in Allied facilities.

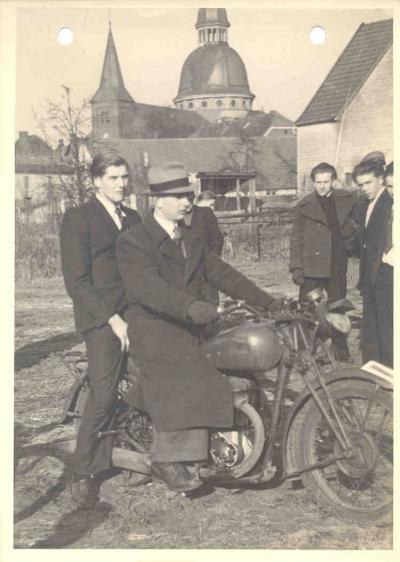

In this respect, training and further training courses, supported by the occupation authorities and the social authorities, was an alternative form of employment for the DPs, although this was primarily vocational. In Maczków there were seven craft businesses and workshops, including a tailor, a toy manufacturer and a watchmaker. There was a great demand for employment in the car repair shop, where it was also possible to obtain a driving licence. DPs benefited from a small payment for all the products manufactured in these enterprises.

The activities outside the home, including participation in training courses, allowed people to regenerate psychologically and prepare themselves for an independent life when they left the town. Statistics show that not many citizens in Maczków were able to find work. According to data collected in March 1947, the town had 4,443 inhabitants, of whom 2,876 were capable of work. However, of these only 896 people took up employment, while the remaining 1 980 were jobless, a rate of 68.8%.

Job policies changed in 1947, when the occupation authorities decided to integrate the DPs into the German economy in order to reduce the running costs of their stay and relinquish responsibility for their plight. However, the DPs were very reluctant to accept this new concept, as their earnings were to be paid in DM with no possibility of exchanging it for foreign currency. In addition, they were not allowed to purchase valuables and, in the event of their return home, to export money. Some of the people opposing these regulations were employed for two years by units of the British Army of the Rhine.

Health services

By April 1945 the occupation authorities had already handed over the 100-bed Haren hospital to the Poles. Five Polish doctors and seven nurses were employed here, while German nuns also worked as nurses.

At that time there were many severely afflicted people in the town. Years of imprisonment in camps, which combined extreme suffering with hard work, had left their mark on their health. Many were exhausted and needed rapid medical help or outpatient treatment. Many others suffered from trauma. Numerous deaths occurred in the first weeks of freedom.

In order to prevent the outbreak of an epidemic, special attention was paid to compliance with hygiene regulations (there was a mass use of DDT powder). Compulsory vaccinations were also introduced to combat typhoid, measles and diphtheria. Despite rumours to the contrary, there were no reports of the spread of venereal diseases among DPs. From September 1945 to February 1946, 980 patients were treated in the hospital in Maczków. Only 16 were diagnosed with venereal disease (from a total population of 4,800).

The call to return home

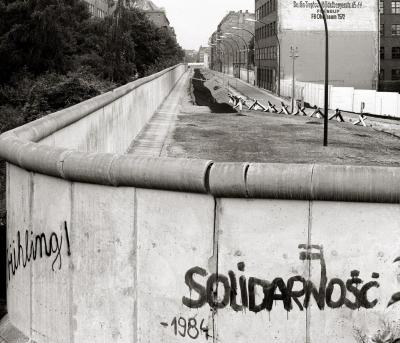

After the war the new government in Poland did everything in its power to bring back its compatriots in exile. Their agitation took the form of political indoctrination aimed at dividing the Polish communities that had formed in the West. The political situation in Poland, the shifting of the borders and the associated loss of homes caused great suspicion amongst many Poles. Hence they initially hesitated to follow such appeals and later completely refused to return to their home country.

After Great Britain recognized the Warsaw government in summer 1945 the Western Allies put increasing pressure on the Polish refugees to return home, as their large numbers were becoming politically and economically problematic. On the one hand, people knew what they could expect to find in their devastated homeland, and longed to be reunited with their families. On the other hand, there was a broad rejeciton of the Communist government and the policies pursued by the former prime minister in exile, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, who was now deputy Prime Minister in Warsaw. Nevertheless, the Poles had to submit to the new policy with respect to occupied Germany. In the following years, many Polish residents in Maczków took the opportunity to emigrate to other countries.

The return of the German inhabitants

The withdrawal of Polish soldiers from Haren began in autumn 1946, and in September 1947 the British occupying power returned the town to the Germans. On September 6th1947, 163 of 514 houses were returned to their German owners. In the following months more and more Poles left the city. The last Polish family left Maczków in August 1948 and the town was renamed Haren on 10thSeptember 1948.

After returning to their houses, the Germans complained about damage and missing furnishings. The losses were estimated at about 8,000,000 DM, compensation for which was paid by by the Federal Republic of Germany, founded in 1949.

Some of the Poles who had lived in Haren remained in Germany. Others decided to emigrate to other countries, mostly Australia, Canada, Palestine or Israel and the USA.

Memories

After the citizens of Haren had recovered their town back from the hands of the Poles, it was hard for them to simply forget this chapter in their history. From a German point of view, as they recalled not without malice, the Polish regime had been an alien occupation. This was reflected in verses like "It sounds like a legend that the plague is now over" or "God protect our Haren from new hordes of Poles" (Reiss, p. 33-34).

Only a few inhabitants of Haren were able and willing to think more deeply about what had happened. The Nazi era was quickly repressed. The concentration camps, the prison camps and their inmates, and the exploitation of hundreds of foreign forced labourers in the town were either forgotten or repressed from their memories. Reservations about dealing with the events was nourished by the fact that no significant acts of war had taken place in the Emsland and that the tragedies of the conquered and occupied countries were hardly an issue. For most citizens of Haren, the war had taken place somewhere else "next door".

Many citizens therefore perceived the arrival of the DPs after the Second World War and the forced evacuation from their homes as the actual beginning of the war. Negative prejudices against DPs and similar groups of people, reinforced by accusations of theft, rape and robbery, stem from this period. Academic research in the 1990s has failed to confirm the persistence of such prejudices. But it does show how easy it was to spread false information and believe rumours immediately after 1945.

Finally, traces of Poland were gradually erased from the town. Polish signs were removed, the old street names returned and inscriptions painted over. There was not even a memorial plaque to inform people about the Polish episode in the history of the town. This situation did not change until the 1990s when former Polish inhabitants visited their town on the Ems. Dialogue with the Germans initially proved difficult, but over time this obstacle was also overcome.

Today the people of Haren no longer doubt that the Poles did not come voluntarily to the Emsland as victims of war, but were forced to do so by historical circumstances. For some years now the townspeople have had the opportunity to meet up with contemporary witnesses. Here the local grammar school has played an important role because its students decided to research this era in their town's history. The history of the Polish enclave also found its way into the media. Documentary films were shot and articles appeared in the national press throughout Germany. The Consulate of the Republic of Poland in Hamburg and the municipal administration have now taken over responsibility for the care of Polish graves. A documentation centre for this Polish episode in the history of Haren after the war is soon to be established.

One might almost think that the history of Maczków has become an integral part of Haren's post-war history. The planned centre can certainly become an important cultural institution for initiating research projects to keep alive the memory of the fate of Poles in this part of Germany.

Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, May 2018

Excerpts from literature consulted by the author:

Jan Rydel, “Polska okupacja" w północno-zachodnich Niemczech 1945-1948. Nieznany rozdział stosunków polsko-niemieckich, Kraków 2000 (German edition: Die polnische Besatzung im Emsland 1945-1948, Osnabrück 2002);

Andreas Lembeck, Befreit, aber nicht in Freiheit. Displaced Persons im Emsland 1945-1950, Bremen 1997);

Anne Reis, “Als Haren Maczków hieß“, [in:] Joanna Rzepa (ed.), Frühjahrsschule 2010: Spurensuche. Polnische Kriegsgefangene und Kriegsmigranten in Nordwestdeutschland, Chemnitz, 2014, p. 33-34 (url: http://www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/15662/Rzepa_Spurensuche.pdf);

Articles in www.porta-polonica.de:

http://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/jozef-szajna-maczkow

http://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/jozef-szajna-portrait-von-stefan-sekowski

http://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/tadeusz-nowakowski#body-place