Olga Boznańska

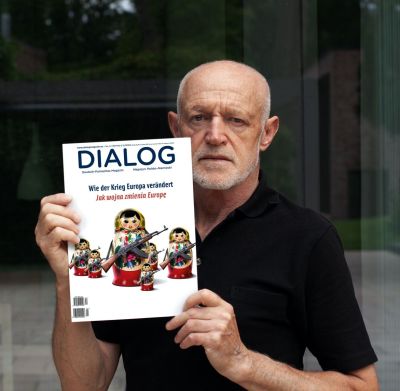

Mediathek Sorted

Olga Boznańska – Kraków, Munich, Paris

Olga Helena Karolina h. Nowina Boznańska was born in Kraków on 15. April 1865. Her mother Eugénie Mondant (1832-1892), was a teacher who came from the French Département of Ardèche; and her father, Adam Gustaw h. Nowina Boznański (1836-1906) was a railway engineer who had trained in Vienna. The family lived in a broad, but not very expensive house that her father had built in the ul. Wolska 21 in 1870, and in which the painter kept a studio for the rest of her life.[1] Her sister Iza was born in 1868. At the age of six Olga received her first drawing lessons from her mother. In 1878 and 1881 the family visited the World Exhibitions in Paris and Vienna. Starting in 1883 Olga received drawing lessons in her parents’ house, from the painters Józef Wojciech Siedlecki (1841-1915) and Kazimierz Pochwalski (1855-1940). She spent her summer holidays in Zakopane. In the following year she began her art studies at the College of Women’s Courses/Wyższe Kursy dla Kobiet , set up and headed by the social activist, Adrian Baraniecki (1828-1891), because women were not allowed to study at the traditional Kraków School of Fine Arts/Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych. She was hugely impressed by the courses in art history given by the academic, Marian Sokołowski (1839-1911) and the literary critic, art critic and historian, Konstanty Maria Górski (1862-1909). Her painting and drawing teachers were the figure and genre painter, Hipolit Lipiński (1846-1884), and the genre and portrait painter, Antoni Piotrowski (1853-1924), both of whom were representatives of the school of realist, colourful and intricate history painters. As a rule students drew portraits from heads made of plaster-of-Paris, and only occasionally from living models. 40 years later Boznańska condemned all her training as an utter waste of time.[2]

In October 1885 (or 1886) Boznańska moved to Munich to continue her art studies because all her life she felt that Kraków was so sad and fearsome.[3] At the time the capital of the kingdom of Bavaria had been the favourite place of refuge for Polish art students for the past two decades. Above all, after the January uprising in 1863, a huge number of painting students who had taken part in the uprising, went into exile in Munich. One of these was Józef Brandt (1841-1915), who began his studies at the Royal Academy of Pictorial Arts in 1863 and opened his own studio in Munich three years later: this soon attracted so many other Polish students that it became the centre of the Munich “Polish colony”.[4] Thanks to its lively art and gallery scene, the two Pinakotheks, the high quality of the professors teaching at the Academy and the tolerant attitudes of its inhabitants, the Bavarian capital was a highly attractive place for foreign students. Even Jan Matejko (1838-1893), who was derided as a dry conservative director at the Kraków School of Art, had studied in Munich in 1858. Above all in the 60s and 70s a number of Polish painters who soon became well-known and indeed famous, had trained in Munich at the Art Academy and at private painting schools: these included Maksymilian and Aleksander Gierymski, Władysław Czachórski, Adam Chmielowski, Józef Chełmoński, Jan Chełmiński, Wojciech Kossak, Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski and Julian Fałat.

[1] The current adress of the unchanged house is ul. Piłsudskiego 21, cf. http://krakow-przewodnik.com.pl/uliczkami-i-placami/ulica-pilsudskiego/, Dom no. 21. Boznańska’s studio in the attic can still be recognised.

[2] Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha: Great, Truly Great Artist. The Krakw of Olga Boznańska, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Krakòw 2014, page 26

[3] ibid. page 28

[4] “Die Polenkolonie: Brandt, Gierymski, Chelminski, Kowalski, Kozakiewicz“, in: Adolf Rosenberg: Die Münchner Malerschule in ihrer Entwicklung seit 1871, Leipzig 1887, page 47

When Boznańska arrived in Munich, not only Brandt had set up his own studio, but also Wierusz-Kowalski (1849-1915), who had arrived in Munich by Dresden and Prague in 1874. Boznańska was carrying letters of recommendation to him and these were clearly helpful during her first weeks in the city.[5] Boznańska’s father had also had previous contacts with Brandt.[6] A huge number of Polish students continued to enrol in the Munich Art Academy. Stanisław Dębicki began his studies there and at the private school run by Paul Nauen in 1884/85. From 1885 onwards the students at the Academy comprised people like Zdzisław Piotr Jasiński, Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz and Feliks Cichocki Nałęcz; from 1886 Wincenty Trojanowski; from 1887 Stanisław Batowski-Kaczor; and from 1888 Stanisław Fabijański and Władysław Karol Szerner.[7] Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski participated in all the important Munich exhibitions. Brandt was made an honorary Professor at the Academy in 1878, and Wierusz-Kowalski in 1890. Both were honoured with the highest Bavarian orders. Like Brandt, a huge number of young Poles studied under the battle and equestrian painter, Franz Adam and the history painter, Carl Theodor von Piloty, both of whom died in 1886. Other Poles were students of the Hungarian history painter, Sandór (Alexander) Wagner (1838-1919): one of these was Czachórski (1850-1911), who set up his own studio in 1879, was also an honorary Professor and remained in Munich for the rest of his life. In 1886 the Hungarian genre painter, Simon Hollósy set up a private painting school, whose summer courses in open-air painting in Hungary attracted the interest of a large number of Polish painting students.

That said, Boznańska neither showed much interest in themes like hunters, Cossacks and Polish horsemen,[8] nor in cavalry attacks, horses and coaches fleeing in snowstorms, “People returning from the Market” or in “Travelling Polish peasants”, all themes that had made Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski well-known, and which were sought after by gallery owners and collectors. Presumably it was precisely the history and genre paintings, i.e. themes from Polish history and popular culture, from which she had fled Kraków. But women were also banned from studying at the Royal Academy of Arts in Munich. Hence Boznańska initially studied at the private studio of Carl Kricheldorf (1863-1934), who was well-known for his portraits of women in peasant and middle-class interiors, and as a painter of portraits and children. She paid regular visits to the Alte Pinakothek in order to study paintings by old masters like the “Lamentation of Christ“ (1634) by Anthonis van Dyck and his portrait of the battle painter, Pieter Snayers (ca. 1627/32), of which she made copies. Her own works from this time, the “Girl in a Hat with Feathers” (1887, Ill. 1) and the “Monk with Wine" (1887, Ill. 2), demonstrate the influence of Flemish painting. This can be seen in the portrait of the girl, which reveals a strong contrast between her bright complexion and black clothes: in that of the Monk, because it is a typical motif, painted in brown and yellow tones, the so-called “gallery tone”. However, both works also show that Boznańska was already far superior to Kricheldorf. In March 1887 she therefore began looking for a new teacher. On a visit, Brandt advised her not to bother about looking for a new professor because she was already a self-confident artist.[9] She exhibited her copy of Van Dyck’s “Lamentation” – it can be seen today in the Polish Library in Paris/Bibliothèque Polonaise de Paris – and the “Monk” in the local exhibition of the Munich Artists’ Cooperative (Künstlergenossenschaft). One year earlier, in 1886 she had already exhibited two other, now unknown, paintings "Camaldolit” and “Old Woman” in Kraków in the annual exhibition of the Society of the Friends of the Fine Arts/Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych (TPSP). She also spent her summer holidays in Poland.

[5] Eliza Ptaszyńska: Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski, on this web portal, page 3

[6] Piotr Kopszak: In Munich, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 37

[7] Lists of Polish students at the Munich Academy drawn up by Halina Stępień/Maria Liczbińska: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim w latach 1828-1914. Materiały źródłowe, Warschau 1994, page 15 ff. Biographies of Polish artists can also be found in the Encyclopedia Polonica on this web portal.

[8] Hans-Peter Bühler: Jäger, Kosaken und polnische Reiter. Josef von Brandt, Alfred von Wierusz-Kowalski und der Münchner Polenkreis, Hildesheim 1993

[9] Piotr Kopszak: In Munich, in: Exhibition cat.. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 38

When she was looking for a new teacher, Boznańska originally thought of the Norwegian portrait painter, Carl Frithjof Smith (1859-1917) and of Paul Nauen (1859-1932), who also worked on portraits and painted pictures of children. Both had studied at the Munich Academy of Arts but neither was accepting students at the time. In the end she decided in favour of the figure, portrait and still-life painter, Wilhelm Dürr (the Younger, 1857-1900), who, since the 1883 Munich Art Exhibition, had been influenced by French open-air painting and by the German naturalists Fritz von Uhde and Max Liebermann. But she only studied under him for a few months. Her choice makes it clear that she was interested in portraits, pictures of children, still-lifes and interiors, themes to which she would dedicate herself almost exclusively for the rest of her life. As she later wrote, she worked industriously from dawn to dusk and scarcely went out.[10] But she did not live a retired life. Her best friend was the painter from Königsberg, Hedwig Weiß (1860-1923), who had also studied under Dürr and Uhde and with whom she shared a studio. Her circle of friends also included the painter from Łódź, Samuel Hirszenberg (1865-1908), who studied in Kraków in 1880 and from 1883 to 1887 under Wagner at the Munich Academy; the graphic artist, painter and sculptor, Ignacy Łopieński (1865-1944), who began his studies under Wagner in 1888; and finally the Warsaw painter and sculptor, Wacław Szymanowski (1859-1930), who moved from Paris to Munich in 1880 to study under Ludwig von Löfftz before opening a painting school in 1891 with another of Wagner’s students, Stanisław Grocholski (1858-1932) in the Munich suburb of Pasing. Boznańska opened her own studio in Theresienstraße in 1889. At some time or other she became engaged to the architect, Józef Czajkowski (1872-1947), who attended art schools in Munich, Paris, Vienna and Kraków between 1892 and 1895.

Under the influence of Dürr and presumably also encouraged by Weiß, who in turn was encouraged by Uhde, Boznańska’s use of colours suddenly became bright and colourful. During these years Uhde was painting children’s scenes where the sunlight fell indoors through the window, illuminating faces and bodies alike, as in the religious scene, “Suffer the Little Children to Come unto Me“ (1884, Museum of Pictorial Arts, Leipzig) and the “Prayer at the Table” (1885, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin), all the way to the “Nursery” (1889, Hamburg Kunsthalle), that was flooded in light. In 1888 Boznańska painted her “Portrait of a Young Woman with a Red Parasol” (1888, Ill. 3) whose main motif is in the background, alongside her subject with her pink complexion and blue eyes, a Bavarian hat and a sweet smelling white Japanese paper umbrella. This was probably based on a somewhat larger pastel work made in the same year by the Polish artist Anna Bilińska (1857-1893), who was living in Paris at the time, and entitled “Woman in a Kimono with a Japanese Parasol”, whose motifs often corresponded with those of Boznańska.[11] Works by Bilińska were shown in Kraków between 1883 and 1895, in Munich in 1890 and 1892, and at the International Art Exhibition in Berlin in 1891, where Boznańska also exhibited. There is no proof that the two artists knew each other. Nonetheless, during this time Boznańska had a particular weakness for Japonism, the copying of motifs and composition principles from Japanese coloured woodcuts. In 1889 she painted the portrait of a “Japanese Woman” (Ill. 6) and in 1892 another portrait of a woman carrying a Japanese parasol (Ill. 15).

[10] ibid.

[11] Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat.. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, pages 86-89, ill. 39

Starting in 1860 Japanese coloured woodcuts began to arrive in French ports along with china and tea, from where they reached merchants dealing in Asian goods and antiquities in Paris. They triggered off a fashion for Japan that lasted for decades. One of the first European painters to discover coloured woodcuts in 1862 in the port of Le Havre, was the American, James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), who lived in Paris and London, and who, in the following years painted several portraits of women in Japanese costumes or with corresponding utensils.[12] One of these was a portrait of a young woman standing by the fireside in a sweet smelling white dress and holding a Japanese fan: “Symphony in White, No. 2: Little White Girl” (1864, Tate Britain, London). Very early on, contemporaries recognised a close connection between Boznańska’s paintings and those of Whistler.[13] In 1888 a large selection of his paintings was shown at the III International Exhibition of Art in Munich, where Boznańska was also present with a “Study”.[14] That said, Whistler’s “Little White Girl” was first shown there in 1892, once more alongside paintings by Boznańska.[15] In today’s eyes her “Young Woman with a Red Parasol” seems modern and, if we did not know of the circumstances, we might date it as around 1900, primarily because of her summary treatment of the white dress, which is far removed from Whistler’s finely detailed paintings. But we can also recognise another influence: Boznańska’s somewhat coarse portrait of a “Young Woman” in a characteristic black hat is reminiscent of the well-known pictures of women made by the Munich painter, Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), the sole artist whom Boznańska was later to acknowledge as an important role model.[16] Here we can think of Leibl’s “Head of a Peasant Girl“ (1879, Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister, Dresden), his famous “Three Women in Church“ (1882, Hamburg Kunsthalle) or his ”Girl with a Carnation” (1880/81, Belvedere, Vienna).

The following pictures from her years in Munich proved that Boznańska was grappling with a variety of contemporary and historical directions in art, although this was not always entirely clear. The portrait of a young woman with bare shoulders, also known as the “Gypsy Woman” (1888, Ill. 4), presumably a studio model, is reminiscent of Edouard Manet’s enticing “Bohémien” (1861/62, Louvre Abu Dhabi) with a scarf tied around his head, which originally belonged to a picture of a pair of gypsies, entitled “Les Gitans”. Presumably Boznańska painted her picture during her summer holidays in Kraków, where it was shown in the following year in an exhibition staged by the TPSP, and which later arrived in the National Museum in the city as a gift from the daughter of the architect and deputy mayor of Kraków, Józef Sare (1850-1929).

[12] Klaus Berger: Japonismus in der westlichen Malerei 1860-1920, Munich 1980, page 19, 36-53 etc.

[13] Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat.. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 74

[14] Illustrated catalogue of the III international Art Exhibition (Munich Jubilee Exhibition) in the Königl. Glaspalaste in Munich 1888, Munich 1888, Whistler no. 2452-2465, Boznańska no. 704; online: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0000/bsb00002401/images/index.html?seite=00001&l=de

[15] Illustrated catalogue of the VI International Art Exhibition 1892 in the Kgl. Glaspalaste, 1. June - end October, Munich 1892, Whistler no. 1950-1950b, Boznańska no. 244-245; online: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0000/bsb00002406/images/index.html?seite=00001&l=de

[16] Piotr Kopszak: In Munich, in: Exhibition cat.. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 44

Boznańska’s “Florists” (1889, Ill. 5), one of the artist’s earliest pictures of children and one of her rare genre motifs, was also shown at the same TPSP exhibition: it repeats Manet’s concept in his “Intérieur à Arcachon” (1871, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown), with the table at the window, the urban landscape behind, and an identical view of the wall and part of a window above. But the very many contemporary pictures of women sewing at a window, including those by Uhde (1883, Kunsthalle Karlsruhe) and the Finn, Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905) – by whom an eponymous motif could be seen at the International Exhibition of Art in Munich in 1888[17] – might also have served as models for Boznańska’s “Japanese Woman” completed in the same year (1889, Ill. 6) and oriented on Whistler’s “Little White Girl” with her white dress and similar characteristics. Even more comprehensively she copied Whistler’s painting “From a Walk” (1889, Ill. 7) in so-called “ symphonies of colour”, a narrowly reduced but richly variegated colour scale ranging from black to white and grey tones seen in his “Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1” (1872, Musée d'Orsay, Paris), for the portrait of a mother. Boznańska seems to have taken her daisy blossoms from Whistler’s “Harmony in Grey and Green“, the portrait of “Miss Cicely Alexander“ (1872/74, Tate London); and the umbrellas on her lap from Manet’s “In the Winter Garden” (“Dans la Serre”, 1879, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin). In the same year Boznańska’s work was presented in Aleksander Krywult’s art salon in Warsaw. The critics’ reaction was lukewarm.

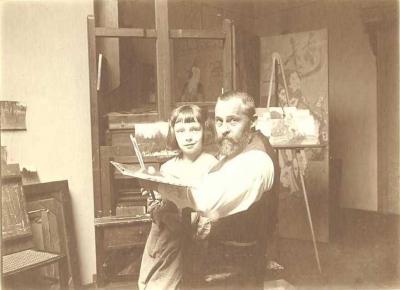

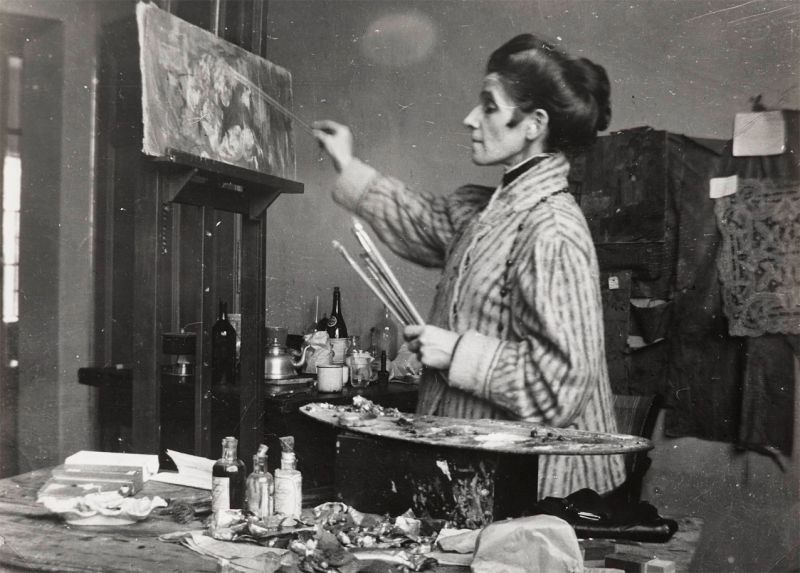

Between 1890 and 1892 Boznańska mostly painted portraits of women and children in Munich and Kraków. The large-scale, representative portrait of Zofia Federowicz (1890, Ill. 8), the daughter of a Kraków town councillor and wife of the merchant and politician, Jan Kanty Ferderowicz (1858-1924), reveals her as a gifted artist who did not shy away from unusual poses and backgrounds and was able to skilfully drape her in a white dress in the composition. The studio wall, on which paintings, reproductions and possibly Japanese coloured woodcuts could be seen, has also been compared to the composition in Manet’s Portrait of Emile Zola (1868, Musée d'Orsay, Paris).[18] The walls in Boznańska’s studio, here presumably in Kraków, but also in Theresienstraße in Munich and, from 1894 onwards in Georgenstraße in the Munich suburb of Schwabing, were indeed covered in loosely hung drawings, reproductions, photos and maps, as is shown in a photo taken at some time between 1892 and 1894.[19] On the painting, as in the same studio photo, a reproduction of one of Diego Velázquez’s portraits of infantas can be seen, probably the “Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Pink Dress” (1653/54, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Boznańska might have seen the series of infantas in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna during a family trip to the World Exhibition in 1881. Two of her young friends from her time at the Baraniecki School in Kraków, Irena Serda (‑Zbigniewiczowa, 1863-1954) and Joanna Seiffman (‑Getterowa), who studied in Munich between 1895 and 1898, also wrote, as did Czajkowski, of Boznańska’s extraordinary interest in Velázquez, that would also later occur to Polish critics writing about her portraits.[20]

[17] Illustrated catalogue of the III International Art Exhibition (Munich Jubilee Exhibition) in the Königl. Glaspalaste in Munich 1888, Munich 1888, no. 920; online: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0000/bsb00002401/images/index.html?seite=00001&l=de

[18] Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 170; Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska (1865-1940), Warsaw 2015, page 111

[19] Olga Boznańska in her studio in Munich, 1892/94, National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Inv. no. MNK VIII-a-rkps-1064/6, pictured in the exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 312

[20] Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 63-74

However, we see the painter searching for a final form in pictures resembling genre motifs. For the “Breton Woman“ (1890, Ill. 9), where an urban landscape can once more be seen through an open window, pictures with corresponding themes from the School of Pont-Aven – those of Émile Bernard, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh – scarcely come into question as role models. Instead her open-air paintings are closer to those of Uhde and Bilińska. The huge format painting, “In the Orangery” (1890, Ill. 10) and the large portrait of a “Girl with a Vegetable Basket” (1891, Ill. 12) show pensive young women, painted against a colourful open-air background, whose objects, a basket of flowers and vegetables, are nothing more than props. Another wall-filling picture, “Good Friday” (1890, Ill. 11), that shows a kneeling nun praying before the cross in the Chapel of the Blessed Salome in the Kraków Franciscan Church/Kościół Franciszkanów.[21] The two salon-format pictures completed in Kraków, “In the Orangery” and “Good Friday” could be seen in the same year in the TPSP. It is almost as if Boznańska wanted to present all her accomplishments to the general public: genre, flowers and open-air paintings, interior, sophisticated perspectives, the various effects of light, not forgetting her large format works.

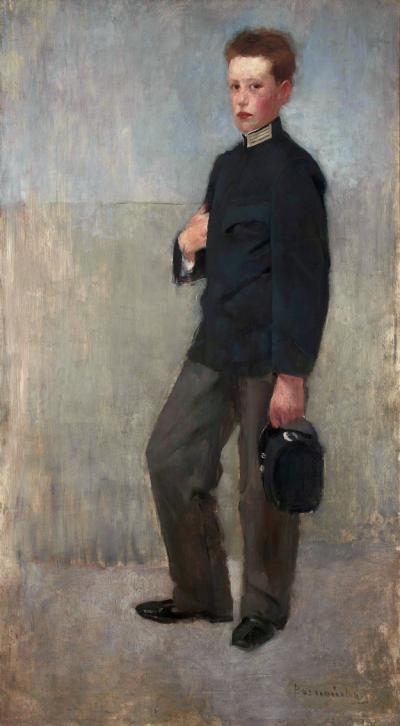

In the same year she returned to making portraits. Her “Portrait of a Boy in School Uniform” (ca. 1890, Ill. 13) reveals her once more as a portrait painter at the height of her powers. Her concentration on a rich palette of grey tones with the red complexion as a lively contrast, once more documents her closeness to Whistler. A clearly defined figure before a background, which is really only one colour, is however reminiscent of Manet’s “Flute Player” (“Le fifre”, 1866, Musée d'Orsay), or the portrait in similar colours of a 16-year old boy, Léon in the “Breakfast in the Studio” (“Le déjeuner dans l'atelier”, 1868, Neue Pinakothek, Munich), or the grey and blue coloured soldiers in front of a grey wall in the “Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico” (1868/69, Kunsthalle Mannheim). Her portraits of ladies, whose faces and hands stand out prominently against the blackness of the dresses, their hats and hairdos, are once more orientated on a picture by Whistler, the “Arrangement in Black: The Lady in the Yellow Buskin” (ca. 1883, Philadelphia Museum of Art): these are the portrait of Boznańska’s mother (ca. 1890, National Museum of Stettin/Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie), the portrait of a woman on horseback (1891, National Museum of Kielce/Muzeum Narodowe w Kielcach), and the unidentified “Portrait of a Woman” (1891, Ill. 14). This is not only unusual for the vivid wallpaper in the background. The excellent presentation of the hands holding a rose twig as if by accident, would arouse much comment two years later at the 1893, Greater Berlin Art Exhibition, where the picture was shown along with “In the Orangery” (Ill. 10).[22]

[21] Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 169

[22] Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 174; catalogue of the Greater Berliner Art Exhibition 1893, p. 19, no. 167: picture no. 169 Im Treibhause, online: http://www.digishelf.de

A much more private character can be seen in the “Portrait of a Woman with a Japanese Parasol” (1892, Ill. 15), which shows an unknown woman in a red dress sitting on a low windowsill. Once again an urban landscape is visible through the window. Japanese parasols can also be made out on wall decorations in the painter’s studio pictures (1890, private collection; Lublin Museum/Muzeum Lubelskie).[23] She is holding one herself on a photograph showing her in a painter’s overall in a front of a table with brushes and tubes of paint, which was taken in 1893 in Kraków (Ill. 16). The red woman might also have been painted in the window of her studio, be it in Kraków or in Theresienstraße studio in Munich, at one of Boznańska’ women friends, or at the home of her fiancé Józef Czajkowski, who began his studies at the Munich Academy in 1892 under the history and genre painter, Johann Caspar Herterich (1843-1905). Around this time Boznańska painted him in a black suit against a coloured background in the style of an open-air painting (National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie).[24] It is presumably Czajkowski, who can be seen in the studio portrait made somewhat later, sitting on a green sofa on the right hand edge of the picture (Ill. 17).

Boznańska’s mother died in Krakòw in November 1892. She then travelled to Paris with her father and sister in order to visit her mother’s relatives. There she also met her cousin, a highly-regarded graphic artist by the name of Daniel Mordant (1853-1914), with whom she henceforth stayed in close contact. Czajkowski went to Paris in 1896 in order to study at the Académie Julian under Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902) and Whistler. In 1900 he returned to live in Kraków. On a brief visit to Paris he broke off his engagement to Boznańska because the two were still living far away from each other. He later worked as an architect, interior designer and professor at the Academy of Arts in Kraków, Wilna and Warsaw.[25]

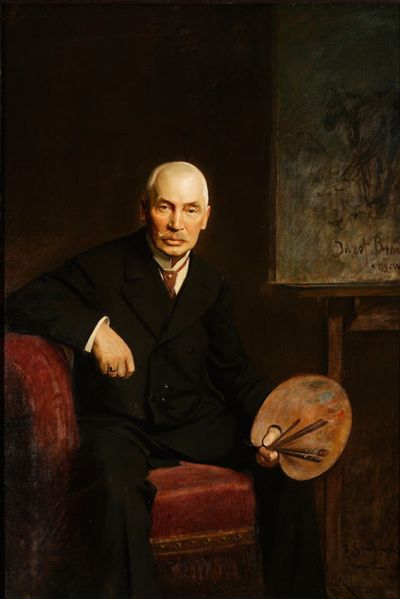

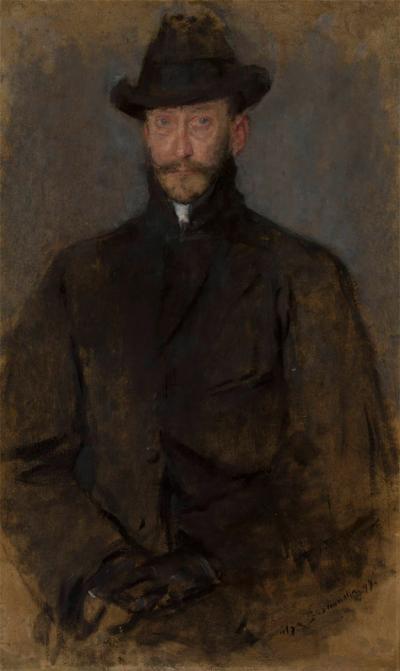

In 1893 Boznańska contacted Paul Nauen, in whose private school she really wanted to study. Hedwig Weiß and another friend, Helena Kossobudzka, who lived in Munich from 1893 to 1900, showed Nauen one of Boznańska’s self-portraits in mourning clothes, which she had completed after the death of her mother. Nauen asked her if he could paint a portrait of her and she consented. True he destroyed the freshly painted portrait before its completion because he thought it did not do justice to the subject. That said, she returned the favour by making a portrait of Nauen (1893, Ill. 18) in a three-quarter length jacket sitting on a flowery sofa next to a small table with a Japanese tea cup in her studio in Theresienstraße. She later said that it had rained that morning and Nauen had arrived at the door with his collar turned up. “That was exactly what I wanted to paint”[26] That same year she was awarded a gold medal for her portrait of Samuel Hirszenberg’s brother shown at an exhibition staged by the Munich Artists’Cooperative. She participated in exhibitions in Prague and in the Berlin Kunsthandlung Amsler & Ruthardt, and travelled to Paris once more to visit her relatives. Her portrait of Paul Nauen was to make her famous all over Europe. In 1894 it earned her a silver medal at the Universal Exhibition of Polish Art in Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv, and a gold medal at the III International Exhibition of Art in Exhibition of Art in Vienna, which was presented to her by Archduke Karl Ludwig, the brother of the Austrian Emperor.[27] The painting was awarded second prize at the 1895 Zachęta exhibition in Warsaw 1895, and in the following year it was purchased by the National Museum in Kraków, the first of her pictures to be bought for a national collection. Her success paved the way for her as a portrait painter in Munich and in Poland.

[23] Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 113, 115; Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska (1865-1940), Warsaw 2015, page 176 f.

[24] Illustration in the exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 175

[25] For Józef Czajkowski, compare the biography in the Encyclopedia Polonica on this web portal and the article by Janusz Antos on culture.pl, http://culture.pl/en/artist/jozef-czajkowski

[26] Marcin Samlicki: Olga Boznańska, in: Sztuki Piękne, 1925/26, no. 3, pages 106-107, quoted from: Piotr Kopszak: In Munich, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 42 f.

[27] ibid. page 43. Compare: Sammlungen und Ausstellungen, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, Neue Folge 5, 1894, Heft 28, 14.6.1894, column 449; online: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de

The whereabouts of a large number of portraits have remained unknown until the present day, either because they are still owned by members of the family or were lost during the Second World War. Others can be found in private collections or were bequeathed to museums. These include the portrait of the dentist, Doktor Woszycki (ca.1896/1899, National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie), her portrait of the painter and stage designer Franciszek Siedlecki (1867-1934), who began his studies in Munich under Franz von Stuck in 1889 and was one of Boznańska’s friends (1896, Krzysztof Musiał collection), her portraits of the philosopher and writer, Michał Henryk Dziewicki (1851-1928) and his sister, the English teacher, Gertruda Dziewicka (both 1897, Princes Czartoryski Foundation/Fundacja Książąt Czartoryskich), also acquaintances of the painter; a further portrait of Czajkowski (1894) and one of Boznańska’s friend, Irena Serda (1896, both National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie). All the subjects in the paintings were portrayed in the manner of Paul Nauen, seated in different poses and with a variety of different colour choices.[28]

The artist also continued to paint self-portraits, some relaxed in everyday clothing (1893, Ill. 19), others critical and in black robes (1896, Ill. 20) or self-confident in her painting overalls (ca.1897, Ill. 21). The paintings were a sort of self-questioning. They were made at regular intervals and in quite a large number, in oil or pastel, on cardboard, canvas or paper in different formats, some sketchy, others representative. They may also have been a way for her to try out different forms of self-portrayal. Boznańska showed them in public and sold them too. For example, in 1906 she exhibited the ca. 1897 large format pastel (Ill. 21) along with other works at the League of Polish Artists “Sztuka”/Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich “Sztuka” in Kraków. It was purchased by the then director, Feliks Kopera (1871-1952), for the Kraków National Museum, but landed in the hands of the collector and art critic, Feliks Jasieński (1861-1929) in exchange for another work. Jasieński, who became well-known for his huge collection of Japanese art, occasionally helped Boznańska to sell her work. In the end he donated the painting once more to the National Museum.[29]

Boznańska also continued with her series of children’s pictures. The paintings, “Girl with Sunflowers” (1891, Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej, Zielona Góra) and “Girl with a White Handkerchief” (1890/93, private ownership) were followed in 1893 by a study of a seated woman holding her daughter in her arms (Ill. 22).[30] The type of girl with golden hair and striking dark eyes – it also featured in the following year in the “Girl with Chrysanthemums” (Ill. 23) – is generally linked to Velázquez’s portraits of infantas, not because of their exact physiognomy but more for their self-confident gaze and independent personality. Also in 1894 she completed the “Portrait of a Woman in a White Blouse” (Ill. 24), possibly a study for pictures on motherhood. Boznańska’s “Girl” pictures had an influence on Józef Pankiewicz (1866-1940), who was painting in Warsaw at the time, and whose “Portrait of a Girl in a Red Dress (Józefa Oderfeld)” (1897, National Museum in Kielce/Muzeum Narodowe w Kielcach) shows a similar type of girl and was also orientated on Velázquez and Whistler.[31]

[28] Illustrations in the exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, no. III.14-21

[29] ibid. page 121

[30] The picture “Study on a Woman with a Girl“ (ill. 22) was originally on the back of the self-portrait in a black robe (ill. 20). It was separated in 1933 on conservation grounds.

[31] Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 73

In 1896 the “Girl with Chrysanthemums” was shown at the International Exhibition of Art in Berlin and at the Vienna Summer Salon. One of the pictures painted in that year, the “Girl in the Garden” (Ill. 25) is exceptionally interesting as a study in colour. In 1898 she completed the painting “Two Children on the Stairs” (Ill. 26): it was exhibited in the year Boznańska moved to Paris, in her exhibition in the Paris Galerie Georges Thomas under the title “Two Red Girls”. In 1904, in the TPSP exhibition in Krakòw, it was bought by the estate owner, Edward Aleksander Raczyński (1847-1926) for his gallery of paintings in the family residence in Rogalin. Boznańska’s “Girl” pictures have an affinity with symbolist paintings, but this is not a complete explanation. The statuesque pose and fixed gaze, a white handkerchief and the white chrysanthemums might point to Franz von Stuck’s picture of youthful “Innocentia” (1889, Manoukian collection, Paris), where the subject is holding a white lily as a sign of her innocence. Stuck’s painting was shown at the 1889 annual exhibition of the Munich Artists’ Cooperative where it immediately found a buyer. In symbolist paintings, the fixed gaze, golden hair, white veil, red clothes and blouses, and hats that resemble haloes, are all symbols for women caught between innocent childhood and blossoming eroticism. Like the emotion before motherhood, huge numbers of this sort of portrait were also painted in this style by artists such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giovanni Segantini and Edvard Munch.

The extraordinary success enjoyed by Boznańska with her portrait of Paul Nauen was made clear in her continually rising number of exhibitions and journeys in the following years. In 1894 she took part in the International Art Exhibition presented by the Munich Secession, with a portrait painting and pastel portraits of two Russians, a “Miss Komonovska” and a “Mr Sviatlovsky”, of whom no more is known.[32] At the Greater Berlin Exhibition of Art she exhibited a painting entitled “Mother and Child” along with a study.[33] In the fourth exhibition of the Londoner Society of Portrait Painters in the New Gallery in Regent Street she received an honourable mention for a portrait of the German-English opera singer, Marie Brema (1856-1925).[34] As well as moving to a new studio in Georgenstraße in Munich (Ill. 27), she paid another visit to her relatives in Paris before embarking on a trip through Europe, with visits to Vienna, Berlin, Weimar, Valencia, Avignon, Geneva, Rapperswil and Milan.

[32] 1894. Verein Bildender Künstler Münchens e.V. Secession: Official catalogue of the International Art Exhibition of the Association of Pictorial Artists in Munich (A.V.) "Secession", page 13, no. 41; pages 33, 323, 324; online: http://digital.bib-bvb.de

[33] Greater Berlin Art Exhibition 1894. Catalogue, page 11, no. 197, 198; online: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de

[34] Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 312

In 1895 she took over the direction of a painting school owned by the landscape and genre artist, Theodor Hummel (1864-1939), for a short time. In the same year she travelled with her sister, Iza, to Switzerland. In 1895, 1896 and 1898 she showed portrait paintings at the International Exhibition of Art presented by the Munich Secession, and also at the Greater Berlin Exhibition of Art in 1895, 1897 and 1898. In 1896 she turned down an offer by Julian Fałat (1853-1929), who had been appointed director of the School of Fine Arts/Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych in Kraków in the previous year, to become head of the proposed department for women. In 1896 and 1897 some of her portraits of children were shown at art shows presented by the Société nationale des beaux-arts in exhibition buildings in the Paris Champs-de-Mars.[35] In 1897 she travelled to Paris with Irena Serda. That year she contributed to a periodical edited by the younger generation of the Polish artist’s community, entitled “Jednodniówka”; these included Czajkowski, Władysław Wankie, Stanisław Radziejowski and Feliks Wygrzywalski. The forty-page periodical only appeared once. It followed the modern artistic design used in the Munich periodical “Jugend“ (English: Youth) that had been founded in the previous year, and contained a loose succession of reproductions of paintings, drawings and vignettes by older and younger Polish painters, one of which was a portrait of a lady by Boznańska, as well as prose, poetry, dramatics sketches and pieces by Polish writers and composers.[36] In 1898 Boznańska had two children’s pictures, “Lad“ and “Girl with Child“, in the exhibition presented by the Berlin Society of Women Artists and Female Friends in the Royal Academy in Unter den Linden.[37] In Kraków she was made a member of the League of Polish Artists “Sztuka”/Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich “Sztuka”, that had been founded in the previous year. In Paris she showed 24 works in a joint exhibition with her cousin Daniel Mordant, presented by the art dealer, Georges Thomas (1842-1915) in his gallery on the Avenue Trudaine.[38] In October 1898 she left Munich for Paris where she moved into an apartment in the Rue Campagne Première No. 17 in the artists’ quarter Montparnasse, not far from the Jardin du Luxembourg.

No one knows exactly why she moved to Paris. She would later say that she followed her sister Iza, who wanted to continue her studies there after a stay in Switzerland.[39] It may indeed have been the case that her family ties and the fact that Paris was considered the capital of European art were the reason for the move. Whereas realism and naturalism were being replaced by symbolism and Jugendstil in Munich in the 90s, Paris was still the city of the Impressionists. Even Whistler had had a studio there since 1892, also in Montparnasse, a few streets away from Boznańska’s future address. She had been orientated towards Paris since 1895 when Mordant had helped her find a place to live in February that year, the closing date for entries to the most important exhibition salons,[40] including that of the Société nationale des beaux-arts on the Champ-de-Mars, where she participated for the first time in the following year. The 1898 exhibition presented by Georges Thomas, which mostly showed young, unknown artists, was not only her first exhibition in Paris but her first success. Here she exhibited portraits, pictures of children, still-lifes, flowers, “Italians“ and a “Breton Woman”, whereas Mordant exhibited graphic reproductions, dry point etchings in the manner of Rembrandt, Rubens, Tiepolo, Delacroix and modern masters like Meissonier, Besnard and Carrière.[41]

[35] Exposition nationale des beaux-arts. Exposés au Champs-de-Mars. Catalogue illustré des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture et gravure, Paris 1896, page VIII, no. 192; Paris, 1897, page VIII, no. 169; online: https://archive.org

[36] Reprint of the publication: Jednodniówka - Eintagszeitung. Neuausgabe, edited by Zbigniew Fałtynowicz / Eliza Ptaszyńska, Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach, Suwałki 2008, also catalogue of the exhibition “Signatur - anders geschrieben. Anwesenheit polnischer Künstler im Lichte von Archivalien”, Polnisches Kulturzentrum, Munich 2008; Digital version of the historic periodical “Jednodniówka“: https://polona.pl/item/373549/8/

[37] XVI Art Exhibition of the Association of Artists and Friends of Art, Berlin 1898, no. 31, 32; online: http://www.digishelf.de

[38] Article on Boznańska’s portrait of the art dealer Georges Thomas, 1899, privately owned, online: http://catalogue.gazette-drouot.com/ref/lot-ventes-aux-encheres.jsp?id=4002557

[39] Marcin Samlicki: Olga Boznańska, Sztuki Piękne 1925/26, year 2, no. 3, page 106

[40] Ewa Bobrowska: Paris of Her Dreams, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 55

[41] Catalogue. Expositions des œuvres de Mlle Olga Boznanska (peinture) et de M. Daniel Mordant (gravure), Galerie G. Thomas, 17, avenue Trudaine, Paris [1898]

Through Thomas she got to know the influential politician and art collector, Olivier Sainsère (1852-1923) who was already a Prefect and State Chancellor, and who became Pablo Picasso’s first patron and collector in 1901. She and Iza were often guests at his house. In 1899 she painted the portraits of the married couple Sainsère, and eleven years later that of the family of their daughter and son-in-law, the doctor and later Nobel prize-winner, Charles Richet (1850-1935), one part of which are in private ownership in France and another part is known through photographs. Around this time Boznańska began to focus her painting style on the complexion of her subjects, in an impressionist manner made up of small coloured marks, with a rough outline of the figure against a background of (mostly) brownish paperboard where the colours could flow. Her impressionist tendencies could be observed at an earlier period, as in the “Study of a Woman with a Girl” (1893, Ill. 22), but now it became a constant characteristic in her paintings. In 1899 she used this style when completing her portrait of the painter, Anna Saryusz-Zaleska (Ill. 28), a school friend from her time in Kraków, and of the painter, Antoni Kamieński (1860/61-1933, Ill. 29), who lived in Warsaw but was often a guest in Paris during these years; a representative portrait of the gallery owner, Georges Thomas (private ownership)[42] and the portrait of an unknown woman in a blue blouse (Ill. 30). Sometimes more, sometimes less, she gave the impression that her subject was somewhat withdrawn and enclosed in a mist of paint. French art critics have linked this phenomenon with Eugène Carriere (1849-1906), who was a close friend of Mordant. But Boznańska decisively rejected this. She saw herself as having a greater affinity to Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940), whom she never got to know personally, but who moved around with Pankiewicz, on whose works she was not so keen.[43]

She continued to paint children’s pictures; the impressionist, brightly coloured painting, “Grandmother’s Name Day” (ca. 1900, Ill. 31); then the misty portrait of a “Nanny” holding a small child on her arm (1899, National Museum in Breslau/Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu); a painting entitled “Motherhood” showing a young woman with her baby (1902, private ownership); the twin portrait of an older girl and a boy (1907, State Art Gallery in Lviv), and finally the completely pink misty portrait of two girls (1906, Ill. 32), whose colour is due to its being painted over by Alfons Karpiński (1875-1961). His later wife, Władysława, can be seen on the right of the picture.

But portraits remained her main area of work. She painted a huge number of portraits of members of the Polish community in Paris, which comprised around 6,000 people at the time,[44] or of Poles, often famous personalities who were in Paris for professional reasons. These included the teacher and literary historian, Dr. Antoni Marian Kurpiel-Łękawski, who received a grant between 1899 and 1900 to study at the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences in Paris (Regional Museum in Rzeszów/Muzeum Okręgowe w Rzeszowie); the biologist and professor, Jan Danysz (1860-1928; 1901, private ownership), the Kraków architect, Franciszek Mączyński (1874-1947; 1902, Ill. 33), who studied at the Paris Academy of Art; and the teacher, translator and social activist, Janina Dygat (1873-1941), the daughter of a Polish émigré, whose portrait was purchased from the artist by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg in 1903, and which later arrived in the Musée d'Orsay via the Louvre.[45] In 1903 she made a portrait of the painter, Maria Koźniewska-Kalinowska (1875-1968, Ill. 34), who had just begun her studies in Paris at the Académie Colarossi, and who also took painting lessons from Boznańska; between 1904 and 1905 she completed portraits of Samuel Hirszenberg (Staatliche Kunstgalerie, Lviv), the pianist and student of Chopin, August Radwan (1867-1958, Ill. 35), and of the teacher and social activist, Zofia Kirkor-Kiedroń (1872-1952, Ill. 36); in 1907 she made a portrait of the art collector, Jasieński (National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie), the Kraków sculptor, Ludwig Puget (1877-1942, Ill. 37), who was studying in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière at the time; and a portrait of the Lemberg painter, Maria Bauer-Papara (1883-1933, Ill. 38), one of her Boznańska’s friends.

[42] Illustration in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 67

[43] Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, pages 82-85

[44] Ewa Bobrowska: Paris of Her Dreams, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 53

[45] Portrait of a Young Woman, 1903. Oil on paperboard, 82.5 x 60.2 cm, signed: Olga Boznańska 1903, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Inv. no. RF 1980 72; online: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/notice.html?no_cache=1&nnumid=016577&cHash=cf8a5f44b4 ; as “Portrait of Miss Dygat” in the exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, no. III, 37

Just as often she painted the portraits of personalities from the French art world and international intellectual circles, like that of the writer, critic and art dealer, Henri Pierre Roché (1879-1959; ca. 1903, private ownership); then Hélène Istrati, the wife of the Romanian microbiologist at the Pasteur Institute, Constantin Levaditi (1874-1953; 1905, private ownership); the American author, Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972; ca.1907, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington), the art critic, Achille Segard (1872-1936; ca. 1910), the critic of the art journal, “Pan”, Pierre Tournier (ca. 1912), the poet, playwright and theatre critic, Baron Édouard Franchetti (ca. 1912, private collection) and many more. Boznańska is generally regarded as the painter who painted the majority of Polish artists and intellectuals to the end of her life, although these could not be counted here. The huge range of her portraits not only documents her social contacts, but is also an impressive chronicle of contemporary Polish and international artistic circles in Paris.[46] Boznańska’s painting studio was one of the main attractions for Poles coming to Paris, alongside the studios of the sculptor, Cyprian Godebski (1835-1909) and the painter, Jan Chełmiński (1851-1925), the Hôtel Lambert, the residence of the Czartoryski family, and the home of the émigré son, bookseller, literary authority, translator and co-founder of the Polish Library, Władysław Mickiewicz (1838-1926), whose daughter Maria welcomed artists in particular with great warmth.[47]

Portraits shown by Boznańska at international exhibitions in Paris and elsewhere were anonymous until around 1913, i.e. the names of the people portrayed were not revealed (Ill. 39, 40), and if so, only with their initials. Thus, in 1910, alongside a picture with “Two Children”, she exhibited the “Portrait of Mr X” (“Ritratto del Sig. X”) at the Czech-Polish Pavilion at the Venice, and the “Portrait of a Woman in Brown” (ca. 1906, Ill. 41), whose identity is still unknown.[48] The three portraits, purchased from the artist at various times by the French state, are also anonymous as is the “Portrait of a Young Woman“, purchased in 1904 from the exhibition salon of the Société nationale des beaux-arts, which has recently been identified as a portrait of Janina Dygat[49]; the picture of a “Young Woman in White” (1912), purchased from the salon in the same year and now decoded as a portrait of Elza Krause, the daughter of the Kraków architect, Józef Sare; as well as the picture of a still unidentified “Madame D …” from the 1913 salon (all in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris).[50]

[46] For comprehensive lists of personalities portrayed by Boznańska, see Ewa Bobrowska: Olga Boznańska and Her Artistic Friendships, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, pages 95-97

[47] Ewa Bobrowska: Paris of Her Dreams, in: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 54

[48] IX esposizione internazionale d'arte della citta di Venezia, 1910. Catalogo, Venedig 1910, page 85, no. 4-6; online: https://archive.org/details/ixesposizioneint00bien

[49] See note 45

[50] Young Woman in White, 1912. Oil on paperboard, 113 x 88 cm, signed: Olga Boznańska 1912, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Inv. no. RF 1980 71, LUX 1038, JdeP 316; online: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/notice.html?no_cache=1&nnumid=016576&cHash=d289ec9e51, as “Portrait of Elza Krause née Sare” in the exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, no. III.60; Portrait de Madame D …, 1913. Oil on paperboard, 117 x 71.5 cm, signed: Olga Boznańska, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Inv. no. RF 1980 73, LUX 999, JdeP 315; online: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/notice.html?no_cache=1&nnumid=016578&cHash=9d0af99753

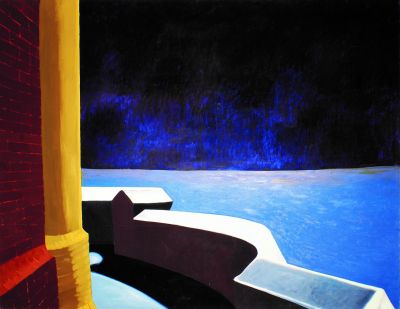

She astutely succeeded in placing her works in the most important European exhibitions. In 1900 pictures of children were shown at the Greater Berlin Exhibition of Art,[51] and her portrait of two “Italian Girls” was shown at the International Art Exhibition presented by the Munich Secession.[52] She received an Honourable Mention at the Paris World Exhibition for her works in the Austrian Section. She took part in an exhibition of Polish artists in the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, and was awarded a gold medal for her works shown in the Women’s Exhibition at Earls Court in London. In 1902, along with the Polish Artists Association, Sztuka, she took part in the 15th exhibition of the Vienna Secession, and showed her works in the Galerie Schulte in Berlin. In the same year the young Polish sculptor, Bolesław Biegas (1877–1954), arrived in Paris, where he befriended Boznańska and her sister, and completed a bronze bust of the painter (Ill. 42). In 1903 two of her portraits were shown at the exhibition of the Berlin Secession,[53] and in 1904 one of her “girls” pictures was shown at the International Art Exhibition in the Düsseldorf Kunstpalast.[54] In the same year she became a member of the Société nationale des beaux-arts, where she had been regularly showing her works at exhibitions since 1896. In 1906 she travelled to Kraków for the burial of her father. Here she painted a view from her studio there (Ill. 43), and completed a self-portrait (Ill. 44).

Back in Paris she painted the view from her new studio on the Boulevard du Montparnasse (Ill. 45). In 1907 she took part in exhibitions on art by women in the Warsaw Zachęta and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. She received a medal for her painting of a “Woman in a Black Dress” (1906, privately owned), in the annual exhibition of the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, where she had taken part for the first time in 1905. In 1908 and once again in 1912, she had her studio renovated in the attic of her parents’ house in Kraków (Ill. 46, 47). In 1909 she exhibited 29 works at a women’s exhibition in the Galerie le petit musée Beaudouin in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. There followed exhibitions in Budapest, Berlin, Vienna and at the Venice Biennale (1910), in Rome (1911), in the Lyceum Club in Paris and in Amsterdam (1912). From October 1912 to March 1913 she lived in Kraków, and spent her summer holidays in the country seat of the Pusłowski family in Czarkowy, before returning to Kraków for the winter. She reached the height of her career on the eve of the First World War (Ill. 48, 49). In a letter to Emanuel Pusłowski written in August 1913, she wrote that in France she had been proposed for the Order of the Legion of Honour, but had been turned down. She was made President of the artists association, Sztuka, and one year later she rejected an offer to become a professor at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts/Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych.

[51] Catalogue of the Greater Berlin Art Exhibition 1900, page 9, no. 148: Woman with Two Children, no. 149: The Childminder; online: http://www.digishelf.de/objekt/71859374X-1900/21/#topDocAnchor

[52] Official catalogue of the international art exhibition presented by the Association of Pictorial Artists in Munich (e.V.) "Secession", Munich 1900, no. 22: Angelina, Kniestück, no. 23: Italiener, Köpfe; online: http://digital.bib-bvb.de . Copy of the painting, “Italians“ in the periodical Die Kunst für alle, vol. 15, 1899/1900, Booklet 22, 15. August 1900, p. 483; online: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1899_1900/0501?sid=661dd481a5c41152a8f9639a2f525b05&ft_query=Boznanska&navmode=fulltextsearch

[53] Catalogue of the seventh art exhibition of the Berlin Secession, Berlin 1903, no. 24, 25; online: https://archive.org/stream/katalogderausste07berl#page/18/mode/2up

[54] Catalogue of the Düsseldorf international art exhibition 1904 in the Städtische Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf 1904, no. 328; online: http://www.agraart.pl/pictures/boz/cat3.jpg

The outbreak of the First World War radically changed her life. The French art market collapsed and income from renting her parents’ house in Kraków failed to reach Paris. There were scarcely any more exhibitions during the war years. In 1915 she took part in shows of Polish art in Vienna and Paris: and in 1918 in an exhibition of Polish painters and sculptors staged in Paris in the palace of Count Felix-Nicolas Potocki (1845-1921), for the benefit of Polish veterans who had been wounded in the war. She spent the winter of 1920/21 once more in Kraków. Friends like Ludwik Puget tried to talk her into remaining in Poland. But nonetheless she handed over the administration of her parents’ house to the accountant and art collector, Edward Chmielarczyk, before returning to Paris to take up her work once more. In solitary hours she created still-lifes with tins, bowls, vases and Japanese figures as well as portraits of flowers (Ill. 50-53). She continued to paint a huge number of personalities from the Paris world of art and international intellectual circles, like the American painter Jane Freeman (1871-1963), who sat as a model for Boznańska’s “Portrait of a Lady with a Threefold Pearl Necklace” (ca. 1922, Ill. 54). Until the end of the 1920s she also created a huge number of portraits of friends in Kraków and Paris, whose names were noted from time to time on the back of the paintings (Ill. 55, 56, 58, 60, 61); or of Polish artists and intellectuals like the doctor and psychologist Melania Lipińska who was living in Paris (Mélanie Lipinska, 1865-1933; ca. 1926, Ill. 57); and the writer and translator, Julia Euzebia ze Skrochowskich Rylska (1884-1969; ca.1930, Ill. 59), who studied in Paris and moved to Kraków in 1926. As usual Boznańska painted all these portraits in an impressionist, more or less pointillist, style.

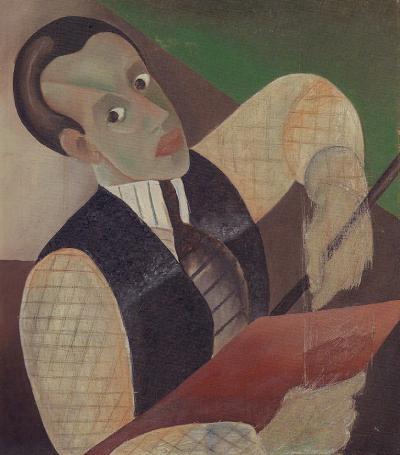

Whilst Paris was celebrating the “wild 20s” Boznańska was by now generally regarded as isolated and eccentric, despite her many social and artistic contacts. The Cubist painter, Alicja Halicka (1889-1974, born in Kraków, educated in Munich and Paris, and painted by Boznańska around 1910 in her “Portrait of Three Sisters“ (National Museum Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie), was later to describe her as “once famous”, but now “unjustly” completely forgotten. “Most of her paintings were portraits that moved between Carrière and Pointillism. She lived on the Boulevard de Montparnasse in a large studio full of mice which were never driven away. ‘They are my friends’, she used to say. As stiff as a poker, hieratic, her face painted with a strange green make-up and her head covered with an out of date mantilla, whose fringes she used to brush off the dust from some of the paintings she wished to show.”[55] Others like the painter Józef Czapski (1896-1993) said that they had met Boznańska at the end of the 20s: “And I remember – I hold the Kapists, (that is to say my group), responsible for the fact that we scarcely took any notice of her. When we arrived in Paris, the conflict between the Abstracts and the Cubists had already begun – the complete Post-Impressionism – and she was still painting as if nothing had happened. Suddenly she disappeared. We failed to give her the necessary credit.”[56]

[55] Alice Halicka: Here. Souvenirs, Paris 1946, page 34

[56] Józef Czapski in a conversation about Olga Boznańska in the Polish Library in Paris on 3. May 1978, quoted from: Exhibition cat. Olga Boznańska, Kraków 2014, page 97

Nevertheless she continued to participate in exhibitions and to receive important awards. In 1925 she was awarded the highest honours at the exhibition entitled Polish Portrait/Portret Polski, mounted by the Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts/Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych in Warsaw, of which she became a member three years later. In 1928 she took part for the last time in the salon of the Société nationale des beaux-arts. Furthermore her works were exhibited in the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science in New York. In 1929 she took part for the last time in exhibitions at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh and the Salon des Tuileries in Paris. In August 1930 she travelled to Kraków where she remained for a year. There, in the following year, the TPSP organised a solo exhibition for her. In 1932 she exhibited for the last time in the Artists Association Sztuka in Warsaw. In the following years her works could be seen in group exhibitions of Polish art in Moscow (1933), Berlin and Warsaw (1935), Paris and Warsaw (1937), as well as in Poznań (1938). A solo exhibition of twenty-seven of her works took place in 1938 at the 21st Venice Biennale.

By the end of the twenties her financial situation had deteriorated dramatically. In 1932 her income, which mostly came from renting her house in Kraków, was no longer enough for her to travel to her home town. The Polish capital and the national Polish Culture Fund supported her to the tune of several thousand złoty in 1934. In the same year the suicide of her sister Iza led her to a physical and mental breakdown. In 1936 the Polish literary historian and publicist, Zygmunt Lubicz-Zaleski (1882-1967) purchased a few of her paintings for the Polish state. In May 1937, thanks to the commitment of the painter, Maja Berezowska (1893-1978) a Committee of Friends of Olga Boznańska/Komitet Przyjaciół Olgi Boznańskiej was set up to collect money to purchase her works through the Warsaw National Gallery. In July 1939, in her Paris studio, she was awarded the Commanders Cross of the Order Polonia Restituta by the cultural attaché at the Polish embassy. Olga Boznańska died in the Hôpital de la Pitié on 26th October 1940 and was buried at the Cimetière des Champeaux (the cemetry of the Polish community) in the town of Montmorency, north of Paris.

Axel Feuß, September 2017

Further reading:

Helena Blumówna: Olga Boznańska, 1865-1940. Materiały do monografii, Warsaw 1949

Olga Boznańska (1865-1940). Wystawa zbiorowa, National Museum in Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Kraków 1960

Helena Blum: Olga Boznańska, Warsaw 1974

Münchner Maler im 19. Jahrhundert, vol 1, München 1982, S. 121 f.

Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon, vol 13, München/Leipzig 1996, p. 485 f.

Jednodniówka – Eintagszeitung. Neuausgabe, edited by Zbigniew Fałtynowicz / Eliza Ptaszyńska, Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach, Suwałki 2008, also in the catalogue of the exhibition “Signatur - anders geschrieben. Anwesenheit polnischer Künstler im Lichte von Archivalien“, Polnisches Kulturzentrum, München 2008

Ewa Bobrowska/Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha (eds.): Olga Boznańska (1865-1940), exhibition catalogue of the National Museum Kraków/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Kraków 2014 (separate Polish and English editions; further reading there)

Renata Higersberger (ed.): Olga Boznańska (1865-1940), exhibition catalogue of the National Museum in Warsaw/Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, Warsaw 2015 (bilingual Polish/English)