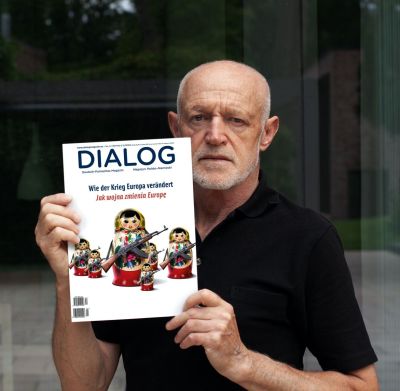

The collectors Joanna and Mariusz Bednarski talk about Polish poster art

Mediathek Sorted

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Pigasus-Gallery - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

The last time I visited your gallery you told me about your collection of Polish poster art. When did you start collecting?

M: At the start it was really an unconscious decision. At the beginning of the 1980s, I was sixteen at the time, Poland was rather gloomy and the only real signs of colour were the posters on the streets. On top of that they were free. Almost every teenager in Poland had posters in their room at the time. We were really proper collectors then. I used to travel once a month from Szczecin to Warsaw in order to go to the theatre and visit galleries, and every time I went to Warsaw I brought back posters. There were thousands of posters in the cinemas. In those days the journey wasn’t easy because the trip from Szczecin to Warsaw took almost 12 hours.

How many different titles are there in your collection today?

J: That’s difficult to say; about 6 - 7000. At the moment I am trying to catalogue the collection. We’ve only put a part of the collection on our homepage.

Posters that are hot off the press are very sensitive. How do store your collection?

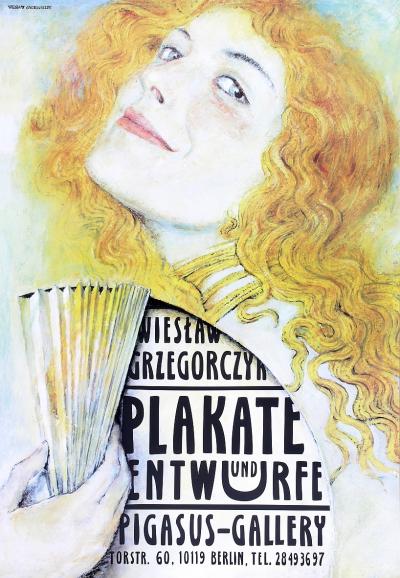

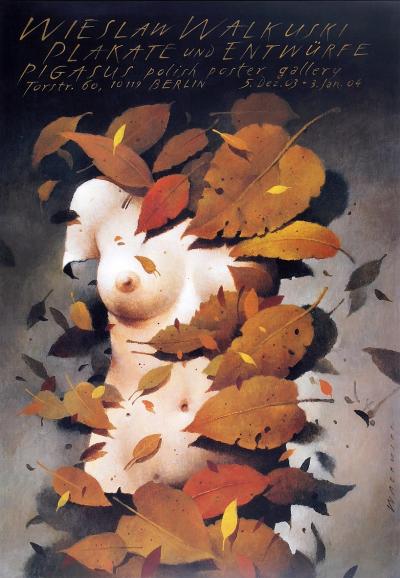

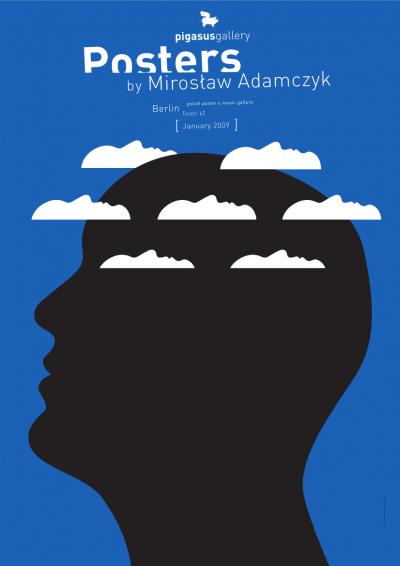

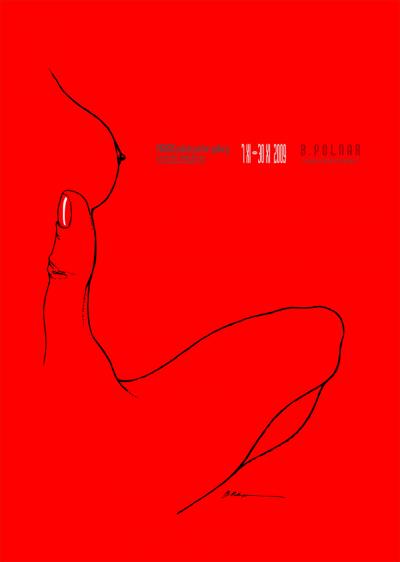

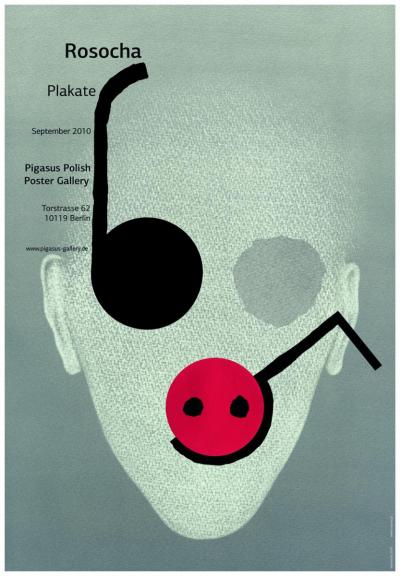

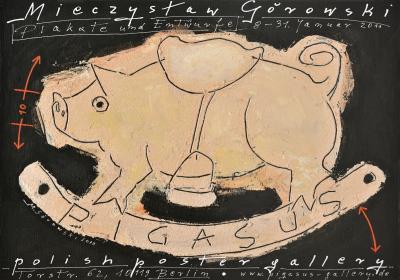

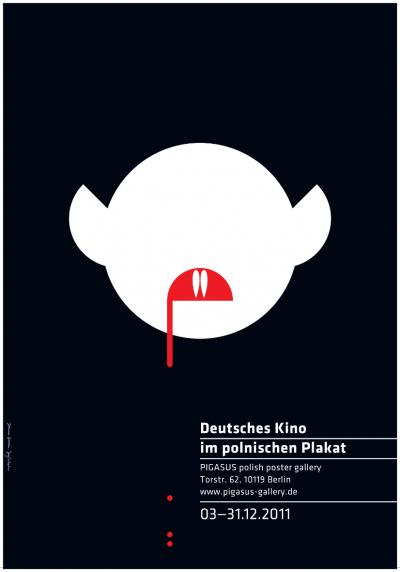

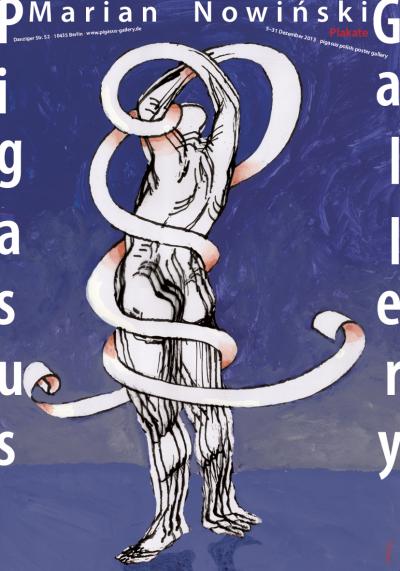

J: Mostly in metal cabinets with drawers – at times we also purchase them second-hand. We can then lie the posters flat. Some of them we take from the Polish Cultural Institute. We keep a few posters in rolls when there are a lot of copies, because we produce a poster for every exhibition in our shop, and this is specially commissioned from the artist in question. If you have a poster gallery it’s only logical to have a good poster for every exhibition. The print run with offset prints amounts to 250 copies which we share with the artist. With screenprints we produce sixty copies.

Do you have any favourite objects in your collection, and are there particularly rare posters?

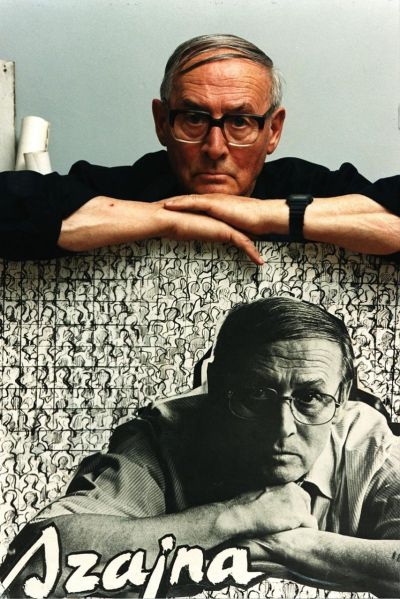

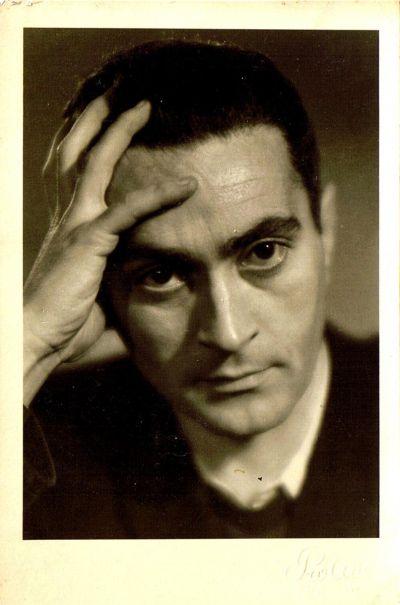

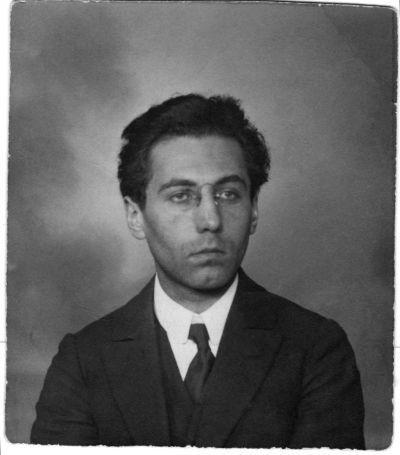

M: Of course we have our favourites and there are also particularly rare posters. I’m not talking about a particular amount but about posters from particular artists. For example my favourite is Jan Lenica, who used to work in Berlin; apart from that Henryk Tomaszewski. A year ago he had a wonderful retrospective in Warsaw. The Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw displayed almost all of his work. It was only when I visited this exhibition that I began to understand Tomaszewski. He is very minimalist.

See you been collecting since the 1980s. But at what point in time did this become a professional collection?

M: With the Internet of course. We first got the Internet in the 90s. It was there that we found out that people not only collected posters but also traded in them. On top of that we got to know a collector from Poznań who came to Berlin every weekend to sell posters from his collection at the flea market on the Straße des 17. Juni. We also got to know other collectors via the Internet. This was the start of a very close exchange amongst collectors. Even now we have an exchange with half a dozen collectors, most of whom live in Poland. We collaborate strongly with the Cracow Poster Gallery run by Krzysztof Dydo. J: Of course there are also people with their own small collections who sometimes have more than one copy of a poster. There are two of these people in Berlin and also a few in other German cities. So all in all we have a very close contact with around ten collectors.

So do you have the largest collection?

M: No, that’s probably the Swiss collector René Wanner. He also has his own homepage: you can see him at many exhibitions all over Europe.

When did you come to Germany and what did you do for a living?

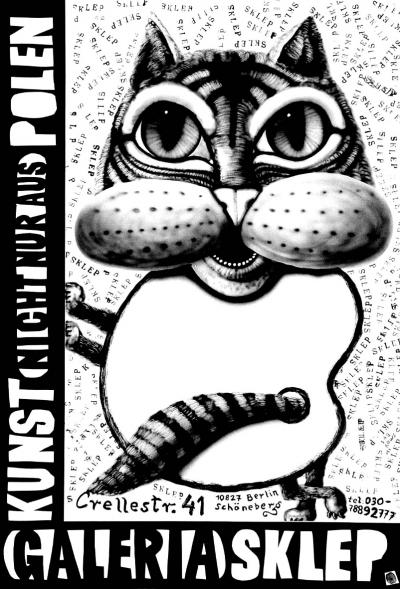

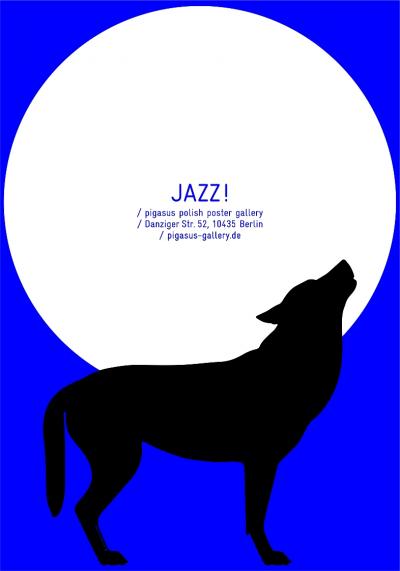

M: I came to Berlin as a student in 1988. I had studied Polish studies in Poland. Here I had to do my A-levels first before going on to take a course in East European Studies at the Free University. After that I got a job at the Polish Social Council as a social worker for Polish immigrants. But I was also responsible for cultural events. J: I came to Berlin in summer 1989. We had known each other for a long time then. If we had married beforehand Mariusz would not have been let out of the country. At that time no one knew that the borders would soon be open. M: One year later I was allowed to return to Poland once more. Eighteen months after that we married in Poland and then immediately returned to Germany. J: I was still studying in Poland. I have a degree in mathematics. However I would have had no opportunity to practice in this area in Germany. So I got a job as a teacher. M: We set up our first gallery, “Sklep”, in Schöneberg in 1999/2000. At the time we already had many friends in Poland who were painters, graphic artists and craft workers. Here we presented exhibitions of their work and also displayed Polish posters. Around two years later we were able to take a reasonably cheap lease on a shop directly next to the Club der Polishen Versager in Torstraße, where we opened the next gallery. This was the first Pigasus-Galerie. Here we only sold posters and music CDs. J: My husband worked as a DJ for years and that explains the connection with music. M: Yes, I worked everywhere in Germany and in Holland as a DJ and also played music from Eastern Europe. So I began to bring more and more CDs from Poland. Today we have around 8000 titles, most of them Polish, but also 1000 Russian and Ukrainian CDs. In April 2012 we moved the gallery once more, to this shop in Danziger Straße.

Is Polish poster art expensive to collect?

M: The prices vary considerably. The most expensive Polish posters are posters of well-known films in the 50s and 60s. Only the best Polish poster artists designed posters for well-known films. There was a committee. Before every release there was a preview for poster artists, who then sketched out their ideas. And from these the committee selected a poster design. At the start only a few artists took part in these competitions. But by the 1980s this had grown to around one hundred. J: In Poland there was a poster for every film that was shown. M: Posters can be very expensive, running into the thousands. The most expensive poster is the one for Hitchcock’s film “The Birds”. It was designed by von Bronisław Zelek. This has since become an icon of graphic design and there’s a picture of it in every handbook. In the 1990s it was sold for over £7000 at a London auction house.

So, on the one hand you have your private collection, and in the gallery you sell your duplicates and CDs. But you also present regular poster exhibitions. How many exhibitions do you have per year?

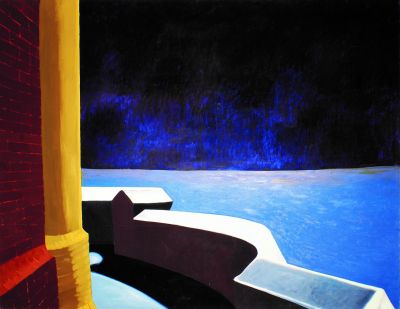

J: We try to put on an exhibition every month, but don’t always succeed. The present exhibition is running for two months. We try to put on 8 to 10 exhibitions a year. All in all we have presented thirty-seven exhibitions, each of which with its own poster. But we also organise outside exhibitions in galleries, museums and cultural sectors. Last year we were in Norway with an exhibition of seventy film posters. In 2004 we had an exhibition in Berlin with theatre posters by three German and three Polish artists. It was held in the Deutschen Herzzentrum, and the proceeds from the sales were donated to heart surgery for children. M: In our gallery we not only present exhibitions from our own collection but also solo exhibitions by current artists. And then of course we also present posters that are not yet in our collection.

Your homepage has a list of over 100 poster artists, with almost as many images. There are alone 123 posters by Henryk Tomaszewski. Have you managed to include all your artists and are you trying to make the list complete?

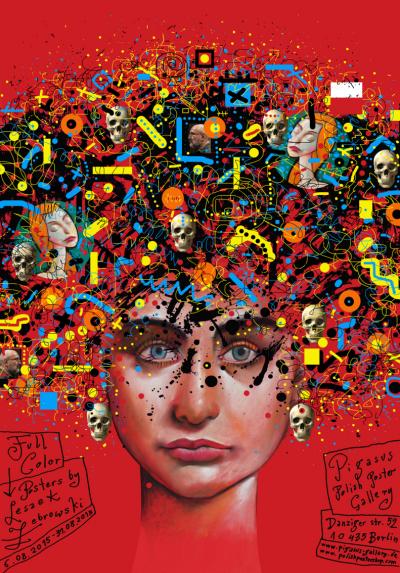

J: It’ll never be complete, for we are always adding new artists. Alone Leszek Żebrowski, whose exhibition is currently running in the gallery, has created over 400 posters. There are between 1500 and 2000 posters by Tomaszewski. The work would take a lifetime. We have to work on our homepage every day, preparing photos and the like. It’s not an encyclopaedic selection. For example our homepage also presents young artists who have maybe only created twelve posters, whereas we have not yet been able to take account of established artists like Bronisław Zelek.

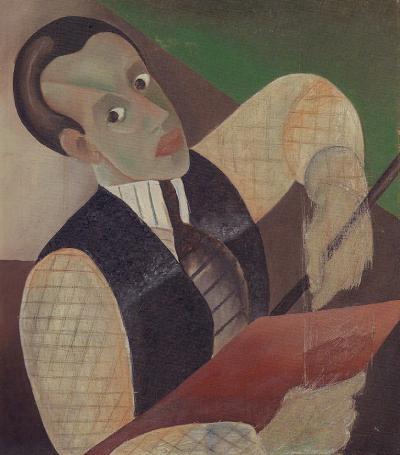

In 1948 Henryk Tomaszewski won five of the nine awards presented at the International Exhibition of Posters in Vienna.

M: Yes, that was the start of Polish poster art after the Second World War. It had a completely new aesthetic.

What did these new pioneering design elements look like?

J: The artists’ individual style was unmistakable. M: That was one thing. Tomaszewski’s particular style was unique. There were also metaphorical elements. Film themes were not simply translated into an image but also encoded metaphorically, abstracted. The posters were poetic, metaphorical and abstract. They did not approach the films directly, there were no portraits of actors, no film scenes like in Hollywood posters, but abstract and expressive figurative symbols. Tomaszewski’s figurative language became increasingly spare. His last posters consisted of only a few signs. And in the end I had some problems with that. I couldn’t understand his signs any more. It was only when I visited the exhibition of his complete works, along with his book covers and a film about him, that I understood the effect his figurative symbols had. You don’t have to have a portrait of Liza Minelli on the film poster. Figurative signs can also arouse people’s attention and encode the contents. J: This does not mean of course that the general public also understands the posters. Whenever there was a new film I always used to look at the poster afterwards. The poster gave an additional meaning to the film. M: In the provinces people certainly didn’t understand and appreciate the posters. Polish poster art became internationally popular about one year after the competition in Vienna. Books were published on it, amongst others by Jan Lenica; and international journals like Graphis in Switzerland dedicated complete editions to Polish posters.

Were film posters the most important area of Polish poster art?

J: Yes, but not solely. There were also of course theatre and opera posters. M: There were no posters for areas like product advertising or fashions, people didn’t need that. J: There were indeed posters for Moda Polska, but they were only intended for trade fairs abroad. In Socialist Poland there was generally no advertising, and none at all for consumer goods. The idea behind the film posters selected by the committee was not so much advertising as art. To a certain extent poster artists had more artistic freedom in Socialist Poland than in capitalist countries since they were not subject to the dictates of commercial advertising. It goes without saying that they had to be politically cautious. Circus posters were another interesting area. M: Nonetheless the political pressure was immense. Every poster had to be passed by the censor. We don’t know why some posters exist at all because politically speaking they are rather critical. Naturally there were also official propaganda posters. For every anniversary of the People’s Republic of Poland there were posters, Lenin posters and so on. A few artists specialised in that area. Others would have never done such a thing.

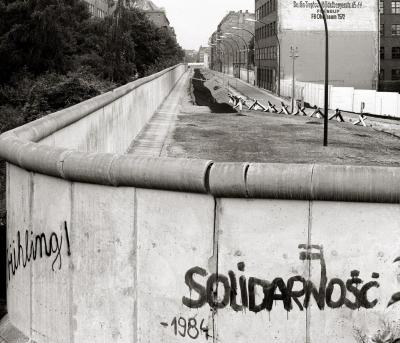

Were there posters on the Solidarność movement?

M: Yes, but they were more or less spontaneously created with the well-known symbol and writing. Tomasz Sarnecki created the famous poster on the first free elections. 1989 heralded the end of Polish film posters. When major American film companies like Warner and Columbia arrived in Poland they brought their own posters with them. All the same there are still film posters for smaller film companies and at cinemas, naturally with a smaller print run. In the 1980s the print runs varied from between 6000 and 22,000; nowadays it’s nearer 300. Circus posters ceased to exist after 1989. It was only after privatisation that new commissions were given for poster art. Nowadays there are many private theatres that receive support from the state and who commission posters. Today it is more the problem that private theatres can no longer afford advertising spots in the city.

Jugendstil posters are an important part of museum stocks. Do you have such posters in your collection?

M: No. These objects are too expensive. They were lithographs with very small print runs.

What do you think of the most recent boom Polish poster art?

M: Today there are two waves. On the one hand there are designers who want nothing more to do with the old school of Polish poster art and have no desire to be called poster artists. They have an international orientation and work exclusively with computer programmes. There’s also a second wave: this consists of artists who orientate their work on the so-called “Polish poster school”, whose greatest models are Tomaszewski and Lenica. Even though they work with computers they have often studied painting beforehand. But today they also produce great posters. J: There is nothing particularly personal about design posters, nothing individual. Naturally there are also good solutions and every theme has its own particular fascination. But it is no longer possible to identify particular artists. Designers orientate themselves on the people who commission them.

Further reading:

Krzysztof Dydo / Agnieszka Dydo: PL 21. Polski plakat 21 wieku / The Polish poster of the 21st century, Krakau 2008

Zdzisław Schubert (Hrsg.): Plakat musi śpiewać! / The poster must sing!, Nationalmuseum Posen / Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Poznań 2012

Dorota Folga-Januszewska: Ach! Plakat filmowy w Polsce, Lesko, 2. ed. 2015