Maksymilian Gierymski

Mediathek Sorted

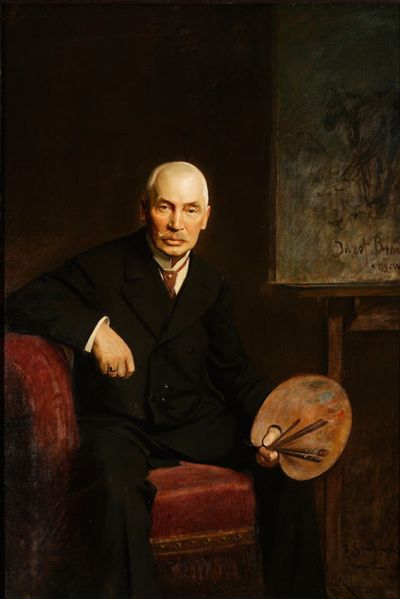

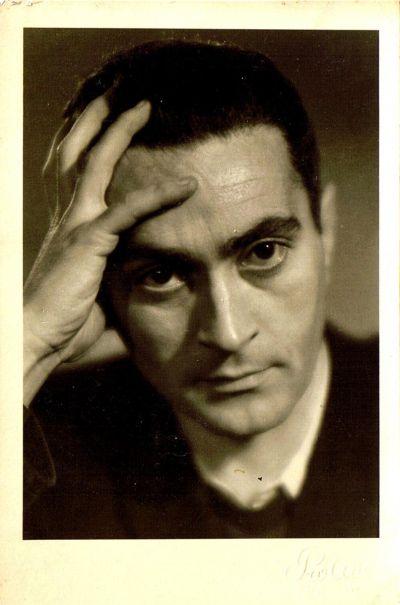

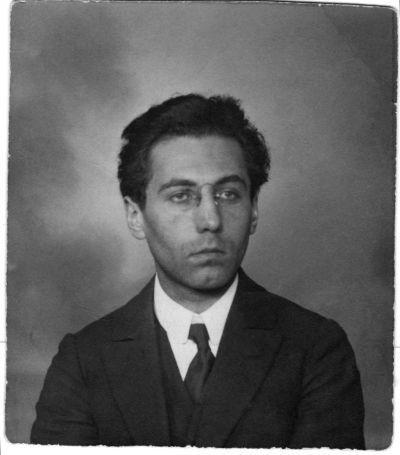

Maksymilian Gierymski was born in Warsaw on 9th October 1846. He was originally supposed to follow a course in technical studies. His father Józef (1800-1875) worked in the administration building of the Armed Forces and was head of the military hospital in Ujazdów. In 1862, after completing his studies at the grammar school in Warsaw in 1862 Maksymilian began a course of studies at the Department of Mechanical Engineering in the Institute for Polytechnics, Agriculture and Forestry (Instytut Politechniczny i Rolniczo-Leśny) in Puławy, but after a few months he moved to the Technical University. Shortly afterwards, during the January uprising in 1863 the seventeen-year-old joined an insurrectionary unit to fight against Russian rule. For almost a year he fought in the region between Lublin and Kielce. After the insurrection was put down he managed to avoid persecution by the Russian authorities, and began to study in the mathematics/physics faculty in the Szkoła Główna Warszawska, a college in Warsaw that ceased to exist in 1869. In 1865 he began studying drawing under Rafał Hadziewicz (1803-1883) in the drawing class (Klasa Rysunkowa) that had been set up only that year. (The School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych) had been closed down in 1864 because of the students’ participation in the January uprising). However Gierymski was so dissatisfied with his lessons that he decided to teach himself from then on, and finally made contact with Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), a painter specialising in horses and hunting scenes who introduced him to painting techniques.

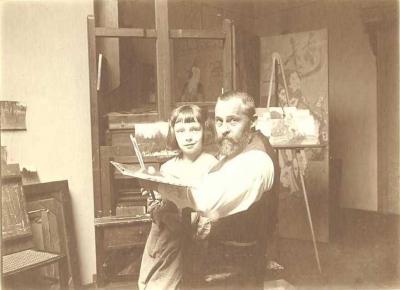

In 1867 with the help of the Russian Governor of Poland who was a fervent supporter of young Polish artists, he was awarded a two-year state grant to study at the Munich Academy of Arts. He matriculated in the antiquity class given by Alexander Strähuber (1814-1882), apparently to improve his drawing ability initially. After that, until October 1868 he studied under the historical painter Hermann Anschütz (1802-1880), his assistant Sándor (Alexander) Wagner (1838-1919) and – together with Juliusz Kossak, who had arrived in Munich in that year – in the private painting school run by Franz Adam (1815-1886), a specialist in horses and battle paintings. Józef Brandt (1841-1915), the most important Polish painter in Munich had also studied under Adam. In later years eight other Poles, including Jan Chełmiński (1851-1925), also attended the same school. Not the least because of a recommendation by Kossak, Gierymski was quickly accepted into the artistic circle around Brandt, who had studied at the Academy under Carl von Piloty (1826-1886) and had his own workshop since 1866. In May 1868 Maksymilian’s younger brother Aleksander arrived in Munich. He had previously also studied drawing in Warsaw under Hadziewicz , and from now until 1872 he continued his studies at the Academy under Strähuber, Anschütz and Piloty. In 1868 Maksymilian became a member of the Munich Art Club and henceforth he was able to participate in exhibitions, sales and prize draws of paintings, organised by the club.

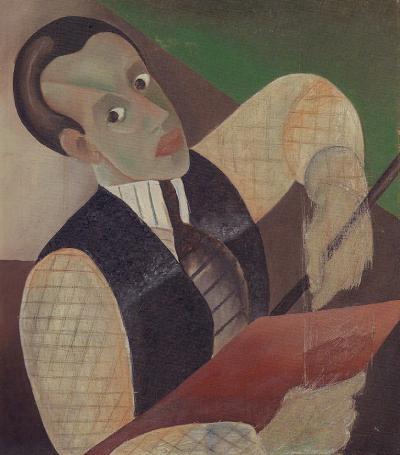

After a comparatively short period of study – he was just twenty-three – by 1868/69 Maksymilian Gierymski was a fully trained and talented painter, as shown by his surviving works from the period. He was not only capable of sketching out dramatic scenes of horsemen containing many figures (Ill. 3); his studies of figures are spotless in their poses, proportions and details, (Ill. 4). After making preliminary studies he was able to paint pictures that were known for their outstanding skill. He had at last found his theme: historic scenes, battles and above all pictures of horsemen like that of a Ulan delivering a dispatch during the November uprising in 1830. (Ill. 7). The presentation of the landscape in this early paintings already shows signs of a modern, almost Impressionist approach, schooled in open-air painting. It was not long before the artist scored his first success. In 1868/69 he was one of the painters in the series of “Munich Illustrated Broadsheets“, a collection that had been published every two weeks since 1848. Gierymski’s works featured wood engravings on the themes of “Pictures from Russia” and “Polish costumes”. In 1869, at the 1st International Art Exhibition in the Munich Glaspalast he exhibited two paintings, “Spinning Room in Poland“ and “Duel between Tarło and Poniatowski“, a scene that had taken place in 1744 between the warlord Adam Tarło and Count Kazimierz Poniatowski; this is one of his “character studies in 18th-century costume” (Ill. 4). In the style of historic themes, from 1870 onwards he painted a huge number of hunting scenes in uniforms from the rococo period, that are simultaneously scenes of the Polish landscape bathed in light (Ill. 9-11, 16). Equally in 1869 he took part in the 1st Major International Art Exhibition in the Vienna Künstlerhaus, at which he sold a work to the Austrian Imperial House.

Such successes meant that people in Munich were queuing up to buy his works, and commissions from Berlin, Hamburg, London, Vienna and other European cities grew constantly. In Poland by contrast – where Gierymski had taken part in the exhibitions of the Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych) in Warsaw since 1865, and from 1867 onwards in exhibitions presented by the Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych) in Krakow – his work was met with incomprehension and criticism from conservative art circles. Hence in 1870 he decided to no longer exhibit his work in Polish partition sectors. Nonetheless he spent his summer holidays in Poland between 1870 and 1872 and also travelled to Warsaw on several occasions in the following two years. In 1871 he travelled to Northern Italy with his brother and visited Venice and Verona. Along with seven other Polish artists from Munich he was part of the German section in the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. Here he exhibited six paintings, all of which were in private hands: they included scenes from the January uprising in 1863/64 which the censor had banned from showing in the Russian sector of Poland. These were the “Alarm in the Insurgents Camp“ and the “Alarmed Vanguard” (Ill. 15), not forgetting the paintings “The Night”, “In front of the Tavern” and two Kossack portraits. For these Gierymski was awarded the Gold Medal.

He began participating in exhibitions at the Berlin Academy of Arts in 1870, and in 1872 was also awarded a gold medal. Two years later in 1874 he was elected an honorary member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Arts. In 1872 he fell ill with tuberculosis following a trip to Poznań, and in the following year he travelled for a cure to Merano and Bad Reichenhall. In 1873 he travelled to Rome with his brother in the hope that he could settle there because of the milder climate. This was where he painted his last picture the “Parforce Hunt” in 18th-century costumes (Ill. 16). But because of a severe deterioration in his health he was unable to complete a further picture entitled “Cavalry Attack”. In summer 1874 he returned to Munich to consult the doctors there. On their advice he returned once more to Bad Reichenhall, where he died on 16th September. His grave in the cemetery there was cleared away in the 1920s. In 1994 the Polish community erected a memorial plaque in his honour.

In December 1874 the Munich landscape and architecture painter Robert Aßmus (1842-1904) published a comprehensive obituary of Maksymilian Gierymski in the Munich art periodical Deutsche Kunst-Zeitung Die Dioskuren, the newsletter of the German Art Societies. This provided details of his life and artistic works (see PDF) and was used as the basis for an article in the Allgemeinen Deutschen Biographie published in 1879. Aßmus had been a friend of Gierymski since 1871 and described him as a master of “atmospheric landscapes, within which historic scenes of horsemen were only “accessories” (German: Staffage). He went on to write: “he particularly loved to create snow effects, and the feeling of rainfall and moonlight:, whereby he either took his large-scale “accessories” from the second half of the 18th century when men wore pigtails rather than wigs, or portrayed Polish insurgents, peasants and Jewish citizens.” To back up his opinion Asmuß quoted the landscape painter and Professor at the Munich Academy Eduard Schleich (1812-1874), who claimed to have given Gierymski the following advice on a visit to his workshop: “Keep painting landscapes, for which you have great sensitivity. Paint landscapes with a large number of accessories.”

Indeed, the term “Staffage” was used to indicate “vitalizing, frequently symbolic figures of people and animals that can enrich a picture, give it a clear depth and emphasise its significance.” Staffages were generally often much smaller in the 18th and 19th century, and this in no way corresponds to Gierymski’s scenes of horsemen. His motifs were derived from personal experience as can be seen in his paintings of the Polish uprisings in 1830/31 and 1863/64 like the “Cavalry Attack on the Artillery” (Ill. 1), “Insurgents in 1863” (Ill. 6), “Ulan with a Dispatch” (Ill. 7) and “The Insurgents’ Patrol” (Ill. 15). Not least, these motifs were highly popular amongst his Munich audience who regarded them as being both documentary and “exotic”. Józef Brandt had made a name and a fortune for himself with similar subjects. Gierymski’s “pigtail pictures” – hunting scenes in 18th-century costumes – quickly became fashionable because the so-called 18th-century decorative “pigtail style” was considered to be highly modern in the households of the wealthy middle-class who regarded it as “late rococo”.

That said, Gierymski’s historical riding scenes were not merely a nod in the direction of people’s taste. As Aßmus wrote, the thing he most wanted to be was a “painter of history. His ideals were the works of Peter v. Cornelius‘, Alfred Rethels, W. v. Kaulbachs and M. v. Schwinds, which revealed the magnitude of artistic philosophy. He was full of enthusiasm for their works which he attempted to emulate.” Evidence of this leaning is provided by his picture of the inn in Soplicowo (Ill. 3) inspired by the Polish national epic poem “Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Lithuanian Foray” (Pan Tadeusz, czyli Ostatni zajazd na Litwie) by Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855). On the advice of his teacher Franz Adam he developed a particular interest in the battle paintings of the French artist Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), a similarity that did not go unnoticed by his contemporaries.

It is also true that Gierymski had a particular preference for nature portraits. Aßmus recalled that he “did not have to look for motifs for his pictures for very long. He mostly dealt with the simplest subjects which would have left hundreds of other artists indifferent. If you were with him in the woods or on a country road […], he would suddenly stop […] and look at a motif that had just appeared. Then his eyes would light up at the site of nature, oh how beautiful, how beautiful, he would call out excitedly with a childlike glee that came directly from his heart.” And later: “Gierymski often used to say that pictures must give viewers the impression that they had just opened the window, looked out at nature and had been surprised by what they saw. ‘Oh that’s just like nature!’ He thought that his most important task was to provide a faithful portrayal of nature, and in so far G was a realist.”

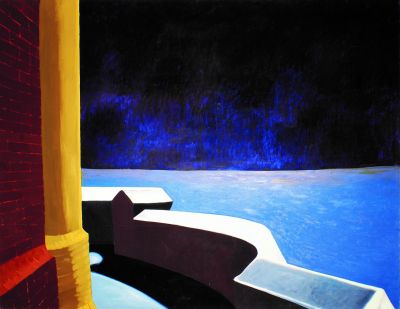

Today the term realists is still used to describe painters of the French Barbizon school – like Rousseau, Dupré, Daubigny, Diaz, Corot and Millet – who left the Paris Academy in 1830 to paint direct from nature in the village of Barbizon in the Forest of Fontainebleau, and capture simple landscape motifs, the so-called “paysage intime”. If German artists had never been to Paris, at the latest they were able to view paintings by French realists and their successors at the 1st International Exhibition of Art in the Munich Glaspalast in 1869. That said, Gierymski’s teachers at the Munich Academy did not teach open-air painting, and he himself was not an open-air painter. Nonetheless from the 1830s onwards it was usual in Germany to go out into the countryside to study and paint sketches in oils. Artists would then return to their workshops to compose landscapes and historic scenes. From Gierymski’s surviving works we know that he made sketches in oils in the countryside around Munich near Schleißheim in the Bavarian mountains, and also during his visits to Poland. Using these as a basis he then created finished paintings in his workshop. Proof of this is provided by his sketches from Poland “In front of the Cemetery” and “Springtime in a Small Town” (Ill. 8, 13), whereby he only composed his painting of “Springtime…” (Ill. 14) some years later in a slightly different variation.

In his workshop he created “atmospheric landscapes” with an “intuitively poetic effect” (Aßmus) from memory and with a trained “romantic imagination”. Paintings from preliminary sketches were executed in meticulous detail. These included the artist’s “Landscape at Dawn” (Ill. 5) and his beloved night pictures (Ill. 2, 12). On the grounds of the landscapes he saw in Poland which he used as backdrops for his pictures of insurgents (Ill. 15) and his rococo hunting scenes (Ill. 9-11, 16), contemporaries regarded Gierymski as the artist who transformed monotonous landscapes under the melancholy grey Polish sky, beneath which broad stretches of sand and large pine forests alternated with uniform heathland and riverside pastures between which streamed the yellow waves of the Vistula, and raised them to motifs worthy of being captured in painting.

Axel Feuß, December 2015

Works in museums:

Art Museum Łódź / Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi

National Museum in Warsaw / Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Silesian Museum, Kattowitz / Muzeum Śląskie, Katowice

Regional Gallery Reichenberg/Liberec / Oblastní galerie, Liberec

National Museum in Poznan / Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu

Art Hall, Kiel

National Museum Krakow / Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie

Upper Silesian, Bytom / Muzeum Górnośląskie w Bytomiu

Braith-Mali-Museum, Biberach an der Riß

Further reading:

Robert Aßmus: Studien zur Charakteristik bedeutender Künstler der Gegenwart CIV. Max Gierymski (obituary), in: Deutsche Kunst-Zeitung Die Dioskuren. Hauptorgan der deutschen Kunstvereine, vol. 19, no. 45, page 357 f. and no. 47, page 377 f., Munich 1874 (see PDF)

Hyacinth Holland, in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 9 (1879), p. 150-151 (www.deutsche-biographie.de)

Maksymilian Gierymski 1846-1874. Malarstwo i rysunek, adapted by Halina Stępień, Exhibition catalogue, National Museum Warsaw, 1974

Münchner Maler im 19. Jahrhundert = Bruckmanns Lexikon der Münchner Kunst in four volumes, vol. 2, Munich 1982, page 27

Ewa Micke-Broniarek (National Museum Warsaw) at www.culture.pl, 2004

H. Kubaszewska, in: Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (AKL), vol. 53, 2007

Birgit Jooss: Zwischen Antikenstudium und Meisterklasse. Der Unterrichtsalltag an der Münchner Kunstakademie im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Eliza Ptaszyńska (ed.): Ateny nad Izarą. Malarstwo monachijskie. Studia i szkice, Suwałki 2012, pp. 23-45

Maksymilian Gierymski. Dzieła, inspiracje, recepcj, exhibition catalogue National Museum Krakow / Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Krakow 2014