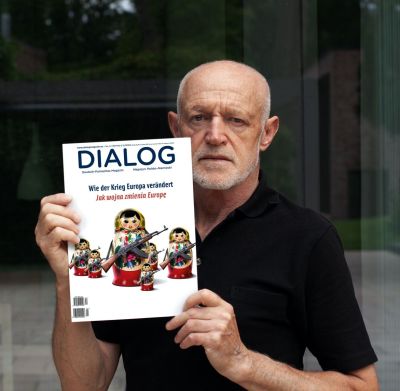

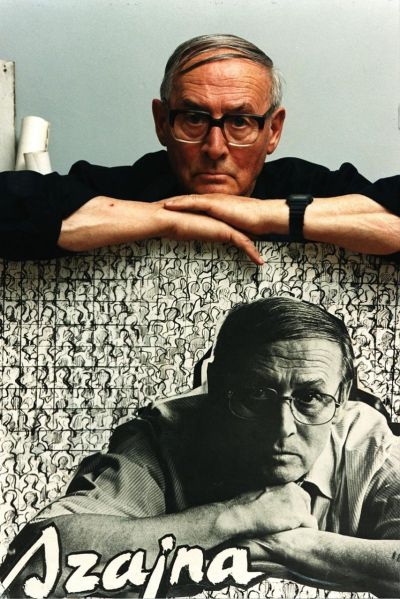

Stefan Szczygieł. His photographic and film work

Mediathek Sorted

ZEITFLUG - Hamburg

ZEITFLUG - Warschau

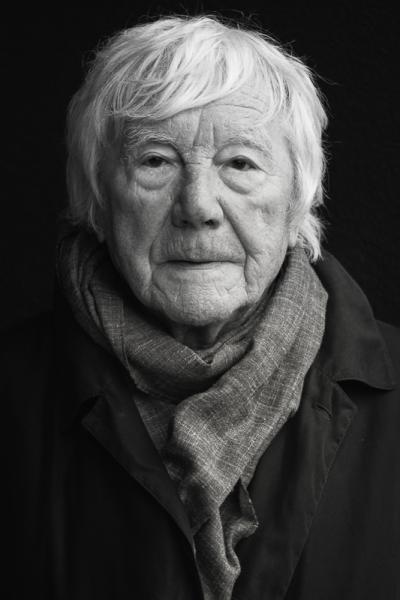

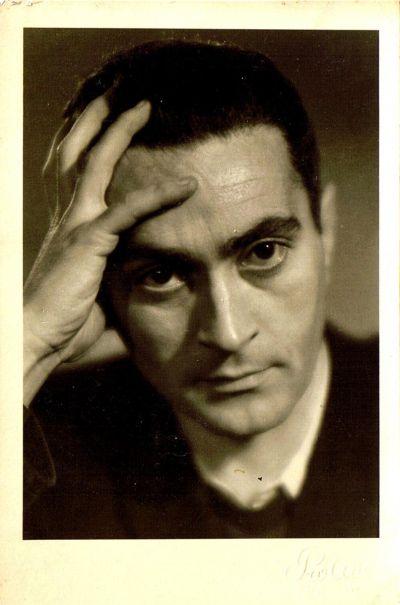

The artist and photographer Stefan Szczygieł was born in Warsaw in 1961, and studied free art at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art from 1984 to 1992, initially in Bernd Becher’s photography class for a few years, and later in the video art class under the pioneer of media art, the Korean, Nam June Paik. In 1993 he moved back home to Warsaw, where he opened his own photo studio and worked as a freelance photographer and artist. Szczygieł earned his living by taking photos for a number of different photo and commercial agencies, and photographic magazines, made portraits of artists, and worked on brochures published by the city of Warsaw. Later he was commissioned to provide photos for a number of different photography homepages. From the early years of the 21st century he also received commissions from institutions, businesses and agencies in Germany.

All his life he maintained a special relationship with Germany in his photographic work. He was especially delighted to receive invitations to present his independent photography and film projects, and was a regular visitor to Cologne and Hamburg. Furthermore he took part in numerous exhibitions in Poland, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway. He died of an illness shortly before Christmas 2011.

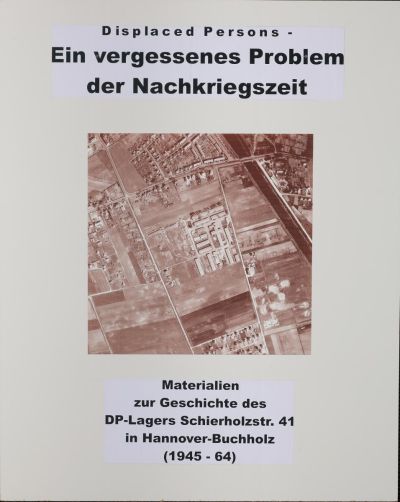

Szczygieł arrived to study in Germany just after martial law had ended in Poland, and in the following year, 1984, more than 550,000 Poles left the country. Contrary to their application, over 50% of them moved to the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin on a permanent basis. Stefan Szczygieł was one of them. He was looking for somewhere to train that was free of ideology and that would allow him to make a career both in Poland and also in the West.

During the Iron Curtain period Western cultural mediators and art experts working in museums and galleries seldom looked towards the east. Despite the political climate there was a groundswell of artists in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary (and also East Germany) who created their own scenes and made a meagre living independent of socialist propaganda and state-commissioned art. Only in the 1980s did people in the Federal Republic of Germany slowly become aware of art beyond the borders of ideology, although job profiles in the fine arts in Szczygieł’s home country, Poland, and in the neighbouring socialist countries were regarded as being utterly without perspective. For decades artists throughout the Eastern block were not taken seriously and excluded from the art markets in capitalist states and nations. Hence they were invisible, and following a profession as an artist was anything but an attractive prospect.

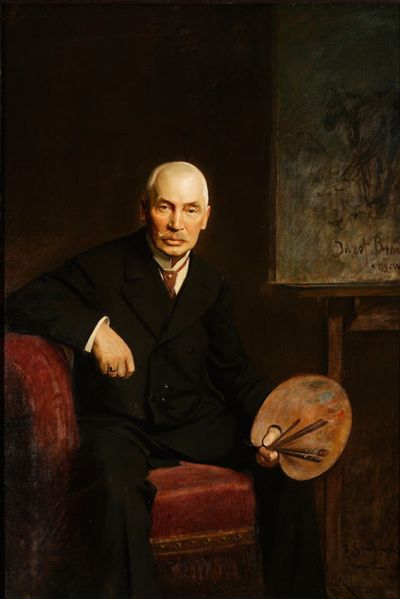

When a period of liberalisation began to make itself felt in Poland Stefan Szczygieł seized the opportunity to apply for a passport and a permit to leave the country. He did not reveal that he aimed to study for some time in Germany. On the one hand he wanted to pursue his passion for photography, and on the other hand make a career by pursuing his independent artistic visions. At the time the experimental character of the Düsseldorf Academy of Art made it a major training centre in new media and photography. The class led by Bernd Becher (1931-2007) was extremely popular with students who wanted to dedicate themselves to artistic and documentary photography. The composer and artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) was the father figure and founder of media art and one of the most important artistic personalities in the Academy.

Both these components, the clear documentary rigour in Becher’s class and the free artistic attitudes encouraged by Nam June Paik run through Stefan Szczygieł’s later work like a thin red line. Here there is one common factor uniting both the teachers and their student: the extremely high precision in their formal techniques and themes and their faithfulness to themselves.

After a period of professional consolidation in the 1990s – Szczygieł was primarily working as a photographer or for commercial agencies and earned enough money to be able to dedicate himself to his own independent projects at the same time, albeit with a certain time lapse – around the turn of the century he was finally in a position to devote himself to artistic photography.

Blow Ups

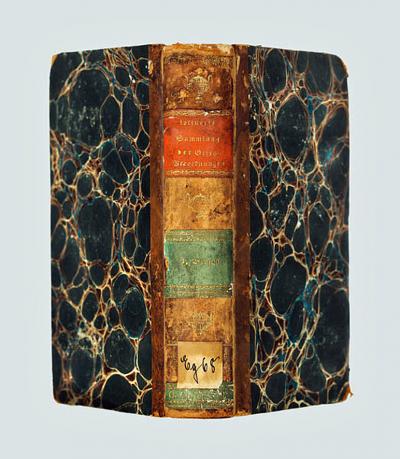

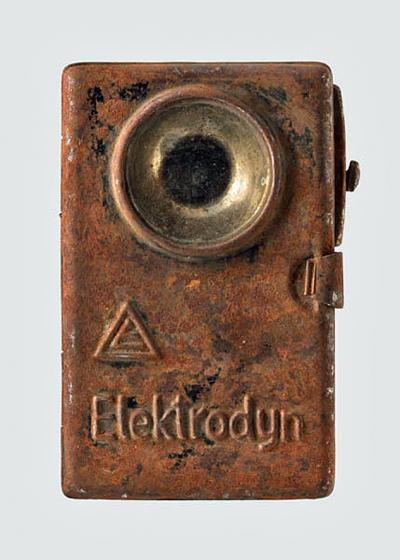

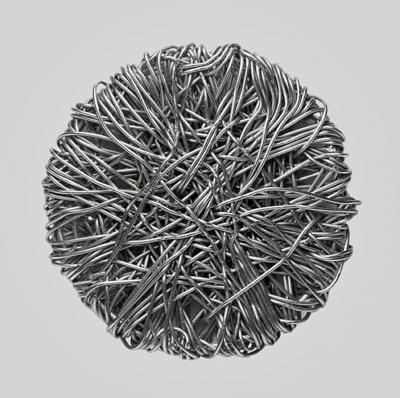

Thus Szczygieł began work on a series of photographs that he entitled Blow Ups or High Resolution Objects, and which he pursued continually for the next five years.

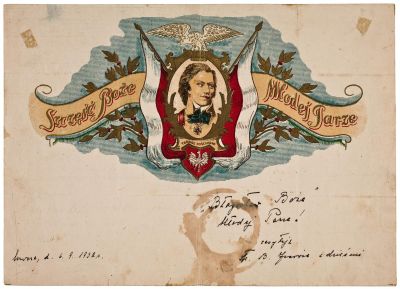

He photographed objects like clocks, telephones, jewellery, cigarette boxes, lighters, books, cameras, coins and buttons – some of them were from the past – in a precise and extremely magnified manner in front of or on top of a neutral background. The proofs were huge, measuring 200 x 200 cm and even up to 200 x 400 cm, up to 200 times larger than the original objects. The huge format and the neutral light grey background in the close ups gave the objects a unique hyper real effect as if they were floating freely in thin air, independent of any laws of gravity. In addition Szczygieł emphasised macroscopic details like scratches, colourings, signs of age, rust, tiny dents and tracings, not to speak of the material density that was fed by an image resolution of up to 350,000,000 pixels.

Szczygieł’s aestheticisation of objects that seem to have lost a little of their soul as a result of their somewhat unquestioning and careless daily use is particularly worthy of mention. In the truest sense of the word he pushes the objects, most of which are mass-produced and seldom one-offs, into a new light, thereby emphasising them as being something special and individual in the world. Thus his focus is not to put the selected objects in an archive or inventory, but to sharpen our perception of them: to allow us to reflect on individual objects from our daily life, to consider more carefully their original conscious use, and to ponder on our indifference to their scarcely-known history. He releases the (almost) forgotten everyday objects from their context without robbing them of their origins. We are therefore able to see the objects in the new light, reconsider the measure of their significance and even define them in a different manner. Every single object in his photographs abducts our attention into a chromatic richness far beyond any documentation. We treasure the things more for their look than for their function and their highly detailed enlargement enables us to experience them in a completely new way. In an essay on Szczygieł published in the New York “Artforum International Magazine” in 2007, the critic Marek Bartelik wrote the following in lyrical tones: “He ventures into the underworld of these old disappearing items revealing their lasting beauty”.

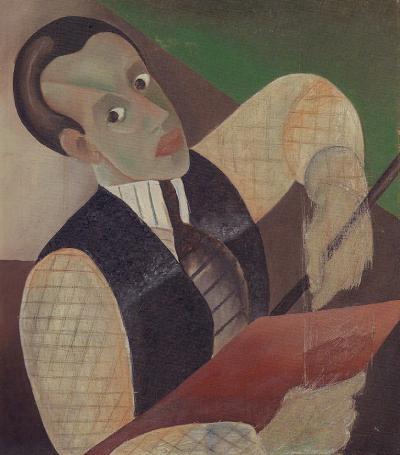

It is precisely the traces of their individual use that define their beauty and allow them to appear like objets trouvés, even to the point of our recognising this dysfunction. Marcel Duchamp’s (1887-1968) idea of “ready-mades” is quoted and correlated here. Even today many people from the world of art and many viewers are suspicious of declaring existing objects to be works of art. By contrast Stefan Szczygieł succeeds in doing precisely this. Via the filter of photography he declares them indirectly as art. This is something he has inherited from his studies and taken over from Nam June Paik.

For the artist blow ups are individual portraits – not of people or personalities, but of objects which once served people or even serve them today, and have their own history.

The titles given by Szczygieł to his large format photographs are not only pragmatic descriptions of the objects but also give details on their origin and where they were created. Indeed the titles in three different languages: German (the majority of the almost 250 photographed objects), Polish and English. Thus the titles are quite simply words like “coin”, “cigarette lighter”, “Lighter, Latarka” (“Torch”), “Guzik” (button) or “silver tin”. By doing so, he not only gives them an international dimension by mediating their cultural and aesthetic origins, but also gives them transcultural dimensions by highlighting common (aesthetic) values, preferences and ideas. Thus the Cedar branch motif (based on the style of Japanese Ukyo-e wood blocks from the so-called Edo period), on a cigarette lighter can be traced back to a preference and yearning for the Far East throughout the whole of Europe, and which inspired and influenced artists in western, central and northern Europe from the second half of the 19th century right until the end of the 20th century.

Szczygieł sees no problem in the fact that his Blow Ups also oscillate between the borders of commercial and artistic photography and superficially transcend them, despite the fact that this forces him to defend his works with art experts. His counterargument is typical for the generation which wrestled with the ideas of the French philosophers from the “École de Paris”. Indeed, directly after the Blow Ups, this led Szczygieł to start a new series of works that equally worked on the way we look at the subject: landscape. Here he talked about “post-modern romanticism” and quoted Jean Baudrillard’s differentiation between the “charm of the real” and the “magic of the concept”. His series of photos takes up Baudrillard’s homogenisation of signs – postulated equally on consumer goods and works of art in his left-wing orientated and Western Marxist early works – and puts them at our disposition particularly because, as far as the photographed objects are concerned, both systems overlap.

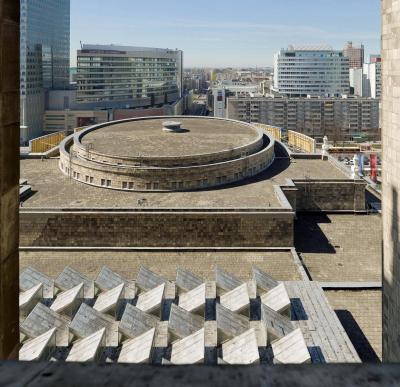

Urban Spaces

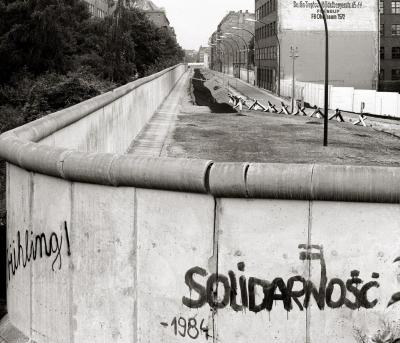

In 2005 Stefan Szczygieł began to change his thematic interests and moved out of his studio. His Urban Spaces project consists of large and medium-format photographs that correlate architecture and urban spaces, building complexes and arterial (i.e. communicating) roads. In contrast to other photographers from the Becher class in Düsseldorf (Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, etc.), Szczygieł in no way portrays urban spaces, architecture buildings and external facades with documentary verve, but in a seemingly neutral, uninhabited and distanced way, that is always related to their everyday use (and wear and tear) by the people who live there; who cross the spaces and live and work within them.

This also differentiates his work from urban photos taken in the 19th and 20th century. True, Szczygieł knew of the famous documentary photographer, Eugène Atget (1857-1927), who captured the huge urban changes in his home city Paris around the turn of the 20th century, and the documentary work of Berenice Abbott (1898-1991) on the renewal of New York in the 1930s and 40s, but these only served him as a contrast to his own ideas of landscape photography. In comparison with other documentary photographers Stefan Szczygieł’s interests were mainly focused on cultural and sociological themes. He revealed the relationship between consumer and aesthetic values and the change in the circumstances of objects and spaces as a result of their use and wear and tear, before submitting his results for discussion.

Alongside inner cities Szczygieł was also highly interested in urban fringe areas and parks, i.e. recreation areas and places where city dwellers could relax in peace. By contrasting green areas on the fringe of cities and the man-made buildings in the city centres he created inevitable points of convergence and threw up many questions. “Urban spaces are not looking for pure “unwounded” nature, but their yearning for such things also resonates with the feelings of city dwellers”, he explained at a press conference at his first exhibition in Hamburg.

True, the photographer began work on his Urban Spaces project in his home city of Warsaw, but he quickly extended his horizons to the surrounding regions, and then to Danzig, Paris, Rome, Cologne and Hamburg.

Sometimes he ironically contradicted the clear strict architectural outlines of buildings with images of petty everyday acts of rebelliousness. A bent traffic sign in front of a new building, building rubble in front of a notable highlight, and graffiti scrawled on walls. Thus he hinted at traces of usage in the same way as in his Blow Ups.

In those years the precision in Szczygieł’s photographs was truly unique. Every detail was amazingly clear and sharp, so that viewers could even note the highly refined features in the background, and the micro areas in the images. It was as if he was inviting viewers to embark on a real journey of discovery through a picture puzzle. We can investigate the frozen city in peace and make a thorough study of the momentary snapshot, but also with a feeling that this moment will soon have passed and that life outside has simultaneously overtaken life in the exhibition room.

This way of working would not have been possible without the immense development of computer technology and digital potentials; and here Szczygieł made full use of computerised potentials. Sometimes this resulted in his being unable to complete his work until the following day, because computer capacities were much more restricted than they are now. Thus there was often a gap of several days between his finding the subject for his photographs, the moment of photography, the computer work and the final photogram. Furthermore Szczygieł continually intervened in the software and command processes in order to ensure clearly defined precise results, not forgetting his freedom of artistic expression.

Initially the exhibitions followed conventional formats; but as his work developed the formats grew ever larger.

Urban Panoramas

Finally Urban Spaces led to a subgroup: to huge photos designated by Szczygieł as Urban Panoramas, and presented in outside spaces, often near or exactly on the place where the photos were taken.

His overall concept foresaw changing the photographs of urban scenes at regular intervals. He would start by installing a photo of a local place in the place itself, but after a few weeks this would be replaced by a new photograph from another city in the same format and in a weather resistant manner. In this way there was not only a past image of the place itself but also of a place in another city in another country – a city within the city. The over-dimensional photographs, initially a confrontation between chronological, spatial and urban links with his own city, were later given another counterpart. Comparable to the Blow Ups, Szczygieł was also provoking us to reconsider the given situation and question the interrelation between perception and usage. The Urban Panoramas are an even more brazen confrontation when another city is brought into play. Thanks to their gigantic size the panorama photos are an adequate counterweight to the passers-by in the city and cannot be interpreted as models or miniature representations.

In this way Szczygieł constructs a learnt identification: 17th century European landscape painting and landscapes in 20th century Cinemascope films recalled these and other iconographic associations and this led to viewers projecting themselves into the landscape. According to their perspective and size they place themselves within the “landscape”, or to put it more precisely, enter the urban landscape, thereby identifying themselves with the city per se and with all the imagery in the photograph. The only difference is that the viewers are not moving through the photo on foot or with a vehicle, but with their eyes. Nonetheless it was extremely important for Stefan Szczygieł to point out – and this functioned particularly accurately with the selection of the photographic excerpts and the exchange of photos from another city like Paris, for example – that landscape painting and artistic photography, as well as documentary photos of urban spaces should be interpreted as revelations of manipulations. In his view the geometry of a city was always a manipulation. This was not only true of the use of the formal language of nature: from a quarry, via Jugendstil to the present day when next-door buildings, parks, the sky and the clouds are reflected in glass palaces and try to fool us that material simulation is the same as the natural product. For him, this is all about manipulating communication. Szczygieł’s work leads viewers to ask questions like: what is the highest building, who built it, in what direction are the streets running and what buildings stand there, at what point do the bridges cross the river and which monuments are dedicated to what or to whom? How long and wide must a street, an avenue or a boulevard be, what were their original functions and which of them have changed in the course of centuries? What is the meaning behind the individualisation of architectural styles and monolithic detached buildings? What effect do huge commercial images have on the city and the people living in it, and what effect does urban illumination have on light pollution?

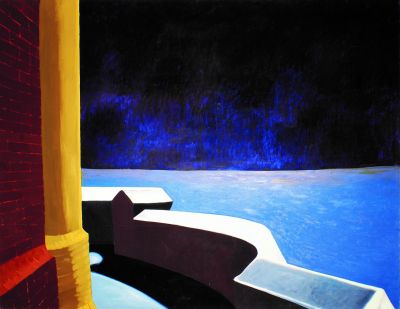

In addition Szczygieł’s use of the word “space” is not only analogue, but more especially technically digital and mentally virtual. In this way anything and everything becomes imaginable – even the manipulation which is no longer (immediately) recognisable. The picture entitled Warsaw, Przystanek tramwajowy (English: tram stop) is a good example of this surreal but also political and social irritation: for the night-time orange and brown illuminated tram stop in the square is dominated by huge posters, advertisements, business logos and lettering that seem like foreign bodies that have been copied and inserted, and which almost completely dissolve the architectonic space. The square suggests that the centre of the Polish capital has been turned into an overwhelming consumer space. All the signets, posters and banners seem to float visibly above the buildings. Just as in university libraries in the USA, where portraits of presidents are often hung above the bookshelves in order to give us the impression that these gentlemen are the guardians of knowledge, when we look at Szczygieł’s picture we begin to think that business enterprises and their expensive advertising are the rulers of the city.

Even in Szczygieł’s other precisely detailed urban landscapes he always leaves a suspicion of digital changes hanging in the air. The artist is fully aware that he is forcing his viewers to confront his works in a thorough and critical manner. This starts with his spatial manipulations and ends with his manipulation of colours. What is known as artistic freedom in painting is quickly turned into seductive manipulation in photography, for the technical possibilities are becoming increasingly perfect with the result that the changes can no longer be seen. Szczygieł exploits this: for it is precisely their precision, their sharply focused details and background that make the photos seem “honest” and “truthful”. When all’s said and done, everything seems to be displayed right down to the tiniest detail.

Thus Szczygieł distantiates himself from the widespread, naive idea that a landscape is nothing but a piece of nature. “Simple” nature was never “landscape” –he seems to want to say – and this also applies to the history of art. The selection of motifs, the composition and arrangement of elements of nature were the things that made up landscape paintings. Nowadays it is possible to melt the elements into one another by digital processing. This even results in putative images of places in the world that have simply been completely (or for the most part), put together on a computer. These are nothing other than images and sequences of images and pictures of alleged “landscapes” that have been assembled like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Looked at the other way around, images of real places – like Szczygieł’s “Tram Stop”, for example – increasingly often give us the impression that we are looking at a computer simulation.

Die Geometrie einer Stadt ist in seinen Augen immer Manipulation. Das gilt nicht allein für die Benutzung der Formensprache der Natur: vom Steinbruch über den Jugendstil bis in die heutige Zeit, wenn sich Nachbarbauten, Parks, Himmel und Wolken in Glaspalästen spiegeln und uns eine Materialsimulation ein natürliches Produkt vorgaukelt. Es geht ihm um die Manipulation von Kommunikation. Szczygiełs Werke führen beim Betrachter zu Fragen wie: Welches ist das höchste Gebäude, von wem wurde es errichtet, in welchem Richtungsverlauf sind Straßen angelegt und welche Bauten wurden dort errichtet, an welchen Stellen überqueren Brücken den Fluss und welche Denkmale sollen woran und an wen erinnern? Welche Größe, Breite muss eine Straße, eine Avenue oder ein Boulevard haben, welche Funktionen hatten sie ursprünglich und welche davon haben sich im Laufe der Jahrhunderte verschoben? Was bedeutete die Individualisierung von Architekturstilen und monolithischen Einzelbauten? Was macht die Großbildwerbung mit der Stadt und mit uns und was städtische Beleuchtung und Lichtverschmutzung?

Zudem wird der Begriff Raum bei Szczygieł nicht nur analog, sondern insbesondere technisch digital und geistig virtuell verwendet und kreiert somit alles was vorstellbar ist – auch die nicht mehr (sofort) erkennbare Manipulation. Das Bild Warschau, Przystanek tramwajowy (dt.: „Straßenbahnhaltestelle“) ist ein gutes Beispiel für diese surreale, aber auch politische und gesellschaftliche Irritation, denn der nächtliche orange-braun beleuchtete Platz mit einer Straßenbahnhaltestelle ist dominiert von Großplakaten, Werbung, Firmenlogos und Schriftzügen, die wie hineinkopierte Fremdkörper wirken und den architektonischen Raum fast vollständig auflösen. Der Platz suggeriert, dass das Zentrum der polnischen Hauptstadt zum übermächtigen Konsumraum geworden ist. Alle Signets, Poster und Transparente schweben weithin sichtbar über der Architektur. Wie in US-amerikanischen (Universitäts-) Bibliotheken, in denen häufig Portraits der Präsidenten über den Bücherregalen aufgehängt sind, um uns glauben zu machen, diese Herren seien die Wächter des Wissens, so werden bei diesem Bild unsere Gedanken darauf gelenkt, dass die Unternehmen und ihre kostspielige Werbung die Wächter und Beherrscher der Stadt sind.

Selbst bei Szczygiełs anderen, präzisen, detailgenauen Stadtlandschaften liegt immer die Vermutung der digitalen Veränderung in der Luft. Dem Künstler ist bewusst, dass sich seine Rezipienten damit auseinandersetzen müssen. Das fängt bei Raummanipulationen an und hört bei Farbmanipulationen auf. Das, was in der Malerei noch künstlerische Freiheit ist, wird bei der Fotografie schnell zur verführerischen Machenschaft, denn die technischen Möglichkeiten, die später nicht mehr sichtbaren Veränderungen, werden immer perfektionierter. Das macht sich der Künstler zunutze, denn gerade durch die Präzision, durch die fokussierte Schärfe bis in die Details und den Hintergrund hinein wirken die Fotos „ehrlich“ und „wahrhaftig“. Es wird schließlich alles haargenau gezeigt.

That said, it is nothing new that we think of as the world is influenced by the way it is perceived and portrayed by artistic media. We only have to think that, in the 18th century, large estate owners – mostly in England, Western and Central Europe – transformed large areas of land into parks and gardens, designed on patterns shown in landscape paintings. Thus landowners once made sure that artificially designed parks with embankments and hills had horizontal lines that conformed to the borders of their property. In this way the landscape was simulated and manipulated at the time. The estate owners saw themselves as being the personifications of creators of landscapes as well as property owners. To them, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Back to nature” was not only a criticism of civilisation but also of cultivation, a counter movements to the coming Industrial Revolution and also a call to “return to images” that were familiar. But these were no less “artificial”. During the course of industrialisation the landscape began to be exploited and transformed to a hitherto unknown extent. Bridges, dams and factories shot up all over the place, and opencast mining carved up whole swathes of the countryside. The idea of landscape has long been reinterpreted and – as with Szczygieł – it is now more of a “cityscape”. In this way the processes described for landscapes can easily be transferred to describe towns and mega cities today, even though urban developments have different effects and definitions. Stefan Szczygieł’s work plays precisely with these phenomena; with questions of hierarchy and property, the sovereignty of definitions and affiliation, and identity and manipulation, even where he makes no attempt at all to influence his work digitally.

Domek

At the same time as Szczygieł was working on his panorama photos he began work on a new small series of photos that he called by the Polish name of Domek (English: little houses/huts). The photos show small, mainly self-built (however, unused or abandoned), decaying allotment dwellings. They suggest a period when people no longer exist in Szczygieł’s imagination and have long since abandoned the surface of the Earth. Nonetheless the things they have left behind them are still rotting there. Getting out into so-called natural surroundings was once seen as an alternative to existing in cramped urban living conditions and the idea was to cultivate nature. Now only transient archaeological relics remain.

Interestingly enough Szczygieł photographs his “Domki” (the plural of “Domek”) in springtime when nature begins to awaken once more. Hence the buds and blossoms on the bushes make an even greater contrast to the abandoned morbid garden huts.

In his Domek too, Szczygieł remains true to his artistic questioning and once more points out relationships between usage, wear and tear, and aesthetics, without commenting in either the one or the other direction. The photos are sufficient unto themselves and scarcely need any “viewing instructions”.

The quality inherent in this series links Szczygieł with other series taken by international photographers. We only have to consider the urban photographs taken by the Americans, William Egglestone and Stephen Shore, or those of a younger generation taken at almost the same time as Szczygieł’s work, like the beach huts o.T. (Gouville) taken by the German photographer, Götz Diergarten. Other parallels can be seen in the Playhouses (plastic garden playhouses for children) made by the Dutch artist Wim Bosch: or in Malte Brandenburg’s Stacked, a series of photos of high-rise blocks in the suburbs of Berlin, and Kevin Bauman’s photo series of 100 Abandoned Houses in Detroit. Within the Polish art scene Szczygieł’s work is uniquely outstanding for its international themes and contexts.

Zeitflug

Between 2008 and Szczygieł’s death in 2011 he shot his first art films with a digital camera. He gave all the films a German title, ZEITFLUG, followed by the name of the respective city (like ZEITFLUG – Warsaw for example). The series of films was shot in a number of different major European cities and not only shows urban and architectural features but, once again, how they are used in public spaces. He pointedly called his films “portraits between affinity and difference”.

Stefan Szczygieł’s films reveal very specific artistic characteristics. By slowing down the shooting speed and giving the result a slow-motion effect he decelerates the urban landscape and gains an important moment of abstraction. Furthermore, since the films were shot in black-and-white, the cities seemed utterly different from real cities with their pulsating speed and frequencies. Nonetheless the films do not seem anachronistic or lifted out of time like the Blow Ups. It is rather the case that Szczygieł used the lack of colour, the deceleration and the resulting degree of abstraction to dis-locate experiential time clearly from real time. Thus we, the viewers, experience the city between two aggregate conditions and this makes it seem new, unseen and extremely innovative. We think the real city has changed places with its cinematic lookalike, or at least has been mixed up with it. In addition Szczygieł’s choice of showing the film in black-and-white suggests a historic component; for we only know this in the form of technically simple, old-fashioned “newsreels” that were shown in cinemas in the mid 1950s.

Thus it is no surprise – indeed it is much more characteristic – that the premiere of the films ZEITFLUG – Hamburg and ZEITFLUG – Warsaw at the 17th Hamburg Film Festival in 2009 in the “Metropolis Kino” took place as a guest showing in the old “Savoy” cinema.

It is worth mentioning a further characteristic in the film series: Szczygieł shoots his films from a slightly lower perspective as if the camera is being held by a child. This makes everything appear to be larger. Even people seem to be taller than they are and this shift in perspective is linked in the minds of the viewers with the idea of “discovery”, just as children discover their surroundings. Indeed, the decelerated, washed out space in ZEITFLUG gives people of all ages a chance to discover the world anew.

Another remarkable factor is decisive for the quality of his films. The passers-by and protagonists do not seem to be aware of the camera. No one looks into the lens, feels observed or consciously reacts to the fact that they are being filmed. No one waves their hand, glances unsurely or turns away, although Szczygieł sometimes comes extremely near. Without using a telescopic lens, the camera show a man’s upper arm, the hands of a woman reading a book, and the wrinkles on the face of a homeless man. We get to see the surfaces of objects just as we are able to observe the material of the headscarf worn by a young woman. The townsfolk move around normally in a completely relaxed fashion as if the camera does not exist. The connection between existence and people’s behaviour on the street, independent of their activities and the way in which Szczygieł uses his camera, turns some of the slow-motion images of the people into stills, in both senses of the word (sculptures and snapshots), and parts of the urban architecture.

By turning and dividing the screen into up to four equal sections adjacent to and above one another, showing simultaneous events and duplications, the artist recreates new patterns of relationships time and time again. Here the city truly flows. The deceleration, the overall rhythm and the time flow is supported by a tailor-made electronic atmosphere and down-tempo music specially commissioned from the Polish composer, Wojciech “Olo” Olszewski. But the electronics engineer, writer and producer also uses the sounds of the real city and integrates them subtly into the events: the laughter of children, harbour noises, the ringing of mobile telephones, ambient noise, bicycle bells, the twittering of birds, cars hooting, the buzz of conversation...

Sadly Stefan Szczygieł’s sudden death prevented him from finishing either his elaborate and demanding Urban Panoramas, or the initial films in his ZEITFLUG series that he had shown and discussed in cities other than Warsaw. Hence his work has remained fragmentary, despite the fact that it has a continuous clear red line.

We can only hope that his early death will not mean that his artistic work will be forgotten. For Stefan Szczygieł was an extremely sensitive, visionary, socially critical, unifying, cultural pioneer of contemporary photography, whose images moved between the real, digital and virtual worlds. Furthermore Szczygieł was linguistically transcultural in his self-evident use of Polish, German and English.

This explorative, innovative, technically adept photographer (if not foreknowing, then always true to his Polish origins) always kept to the oath formulated by architects and town planners in ancient Greece: “I shall leave this city more beautiful than when I entered it“. This could have been Szczygieł’s own maxim.

Claus Friede, April 2017