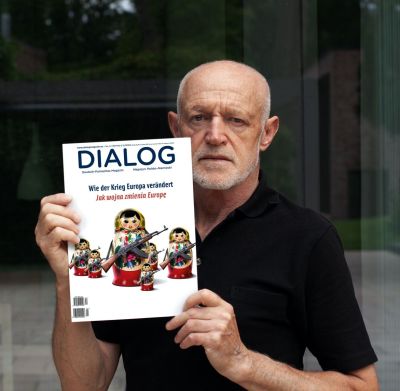

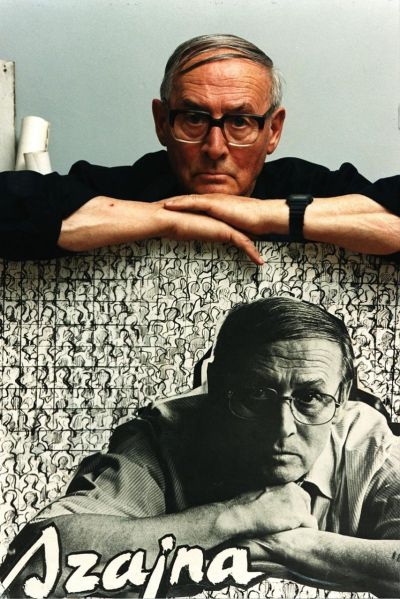

Stefan Szczygieł. His photographic and film work

Mediathek Sorted

![“Feuerzeug” [Cigarette lighter] “Feuerzeug” [Cigarette lighter] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 200 x 300 cm.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/07_feuerzeug.jpg?itok=lVUakM66)

![“Telefon” [Telephone] “Telefon” [Telephone] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 200 x 260 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/09_telefon.jpg?itok=McBWeT4z)

![“Taschenuhr” [Pocket watch] “Taschenuhr” [Pocket watch] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 250 x 200 cm.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/10_taschenuhr.jpg?itok=yuY8kMzC)

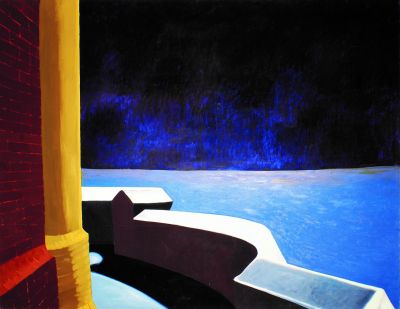

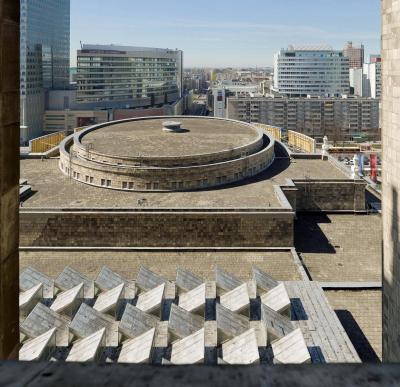

![“Warsaw, Bridge” [Warschau, Brücke] “Warsaw, Bridge” [Warschau, Brücke] - From the series “Urban Spaces”, 2005-2009, Inkjet photo print, 60 x 170 cm (Edition: 10).](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12_warschau_bruecke.jpg?itok=_mrZqMgU)

ZEITFLUG - Hamburg

ZEITFLUG - Warsaw

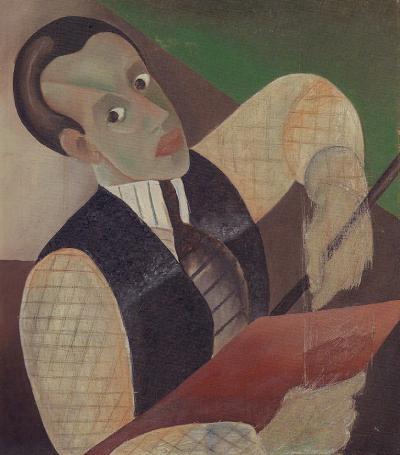

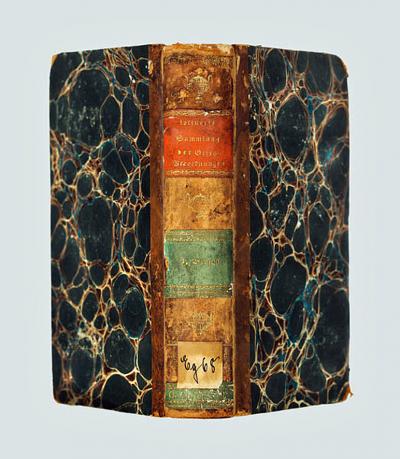

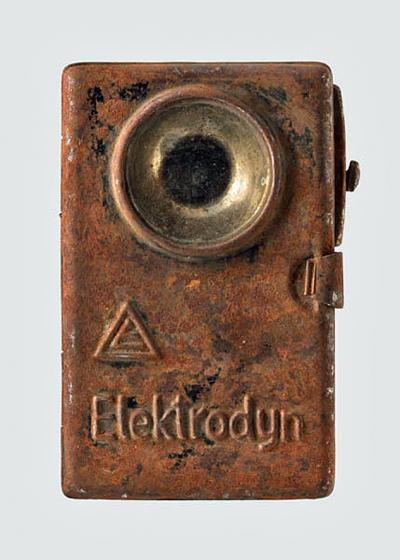

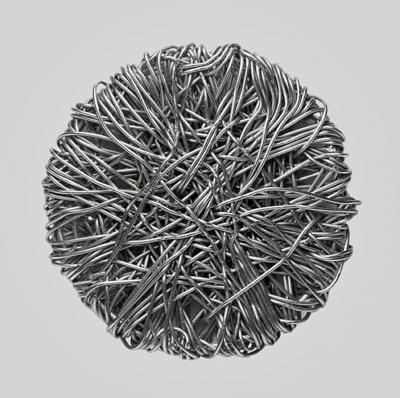

Szczygieł’s aestheticisation of objects that seem to have lost a little of their soul as a result of their somewhat unquestioning and careless daily use is particularly worthy of mention. In the truest sense of the word he pushes the objects, most of which are mass-produced and seldom one-offs, into a new light, thereby emphasising them as being something special and individual in the world. Thus his focus is not to put the selected objects in an archive or inventory, but to sharpen our perception of them: to allow us to reflect on individual objects from our daily life, to consider more carefully their original conscious use, and to ponder on our indifference to their scarcely-known history. He releases the (almost) forgotten everyday objects from their context without robbing them of their origins. We are therefore able to see the objects in the new light, reconsider the measure of their significance and even define them in a different manner. Every single object in his photographs abducts our attention into a chromatic richness far beyond any documentation. We treasure the things more for their look than for their function and their highly detailed enlargement enables us to experience them in a completely new way. In an essay on Szczygieł published in the New York “Artforum International Magazine” in 2007, the critic Marek Bartelik wrote the following in lyrical tones: “He ventures into the underworld of these old disappearing items revealing their lasting beauty”.

It is precisely the traces of their individual use that define their beauty and allow them to appear like objets trouvés, even to the point of our recognising this dysfunction. Marcel Duchamp’s (1887-1968) idea of “ready-mades” is quoted and correlated here. Even today many people from the world of art and many viewers are suspicious of declaring existing objects to be works of art. By contrast Stefan Szczygieł succeeds in doing precisely this. Via the filter of photography he declares them indirectly as art. This is something he has inherited from his studies and taken over from Nam June Paik.

For the artist blow ups are individual portraits – not of people or personalities, but of objects which once served people or even serve them today, and have their own history.

The titles given by Szczygieł to his large format photographs are not only pragmatic descriptions of the objects but also give details on their origin and where they were created. Indeed the titles in three different languages: German (the majority of the almost 250 photographed objects), Polish and English. Thus the titles are quite simply words like “coin”, “cigarette lighter”, “Lighter, Latarka” (“Torch”), “Guzik” (button) or “silver tin”. By doing so, he not only gives them an international dimension by mediating their cultural and aesthetic origins, but also gives them transcultural dimensions by highlighting common (aesthetic) values, preferences and ideas. Thus the Cedar branch motif (based on the style of Japanese Ukyo-e wood blocks from the so-called Edo period), on a cigarette lighter can be traced back to a preference and yearning for the Far East throughout the whole of Europe, and which inspired and influenced artists in western, central and northern Europe from the second half of the 19th century right until the end of the 20th century.