Poles in Germany: Roads to visibility

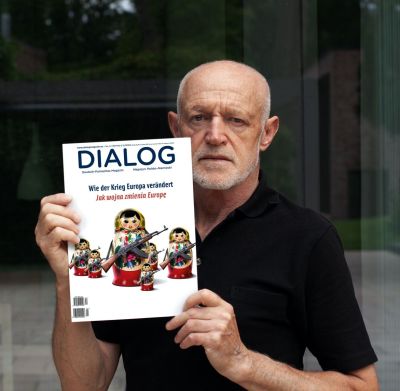

Mediathek Sorted

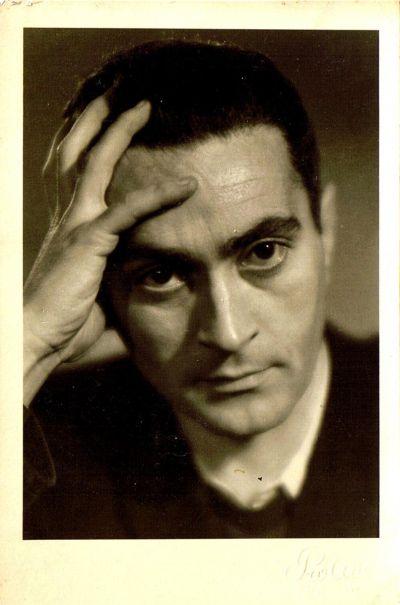

"Pola Negri - unsterblich", Dokumentation von 2017

„Drei Tage im November. Józef Piłsudski und die polnische Unabhängigkeit 1918“

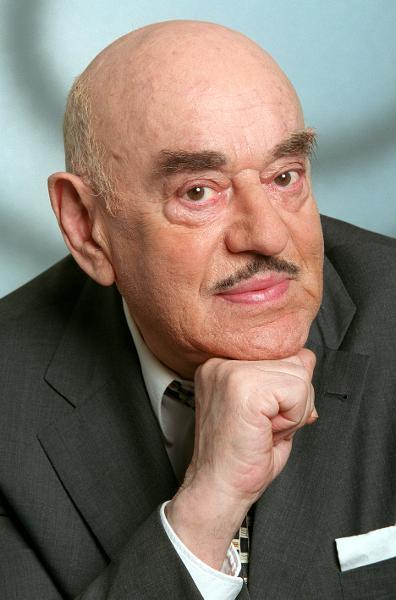

Artur Brauner - Ein Jahrhundertleben zwischen Polen und Deutschland

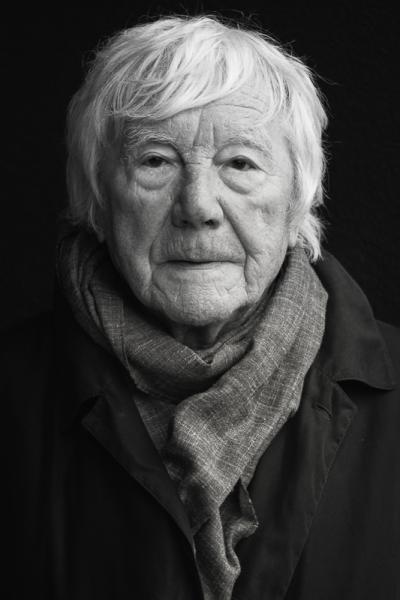

Teresa Nowakowski (101) im Gespräch mit Sohn Krzysztof, London 2019.

Karol Broniatowski

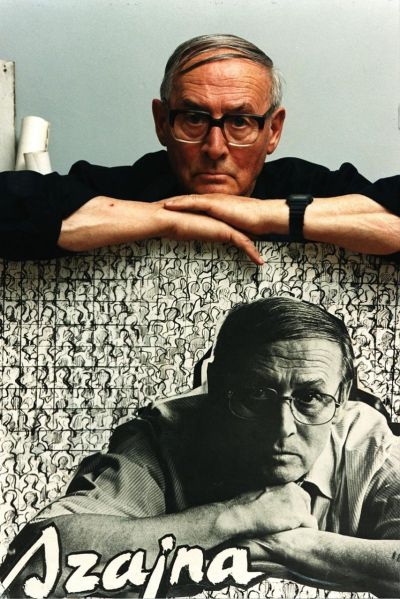

Film "The Madman and the Nun" - St. Ignacy Witkiewicz, Filmstudio Transform, Director: Janina Szarek

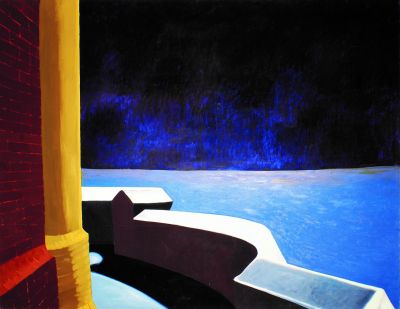

WORMHOLE, 2008

Interview with Leszek Zadlo

ZEITFLUG - Hamburg

Der Planet von Susanna Fels

Migratory people

Over the centuries, people have migrated from Polish to German territories. Generally speaking, though, this was not mass migration, as opposed to the migration movements from west to east which, since the High Middle Ages, had seen large populations of German-speaking people streaming into eastern Central Europe in the course of territorial expansion (“Ostsiedlung”). Representatives from the elite in particular made to move to the West. These included a number of Polish princesses, predominantly from the Jagiellonian dynasty. The most well known of these must surely have been Jadwiga (Hedwig), a daughter of King Kasimir IV, whose wedding to Duke Georg the Rich of Bavaria-Landshut in 1475 was celebrated with a lavish celebration.

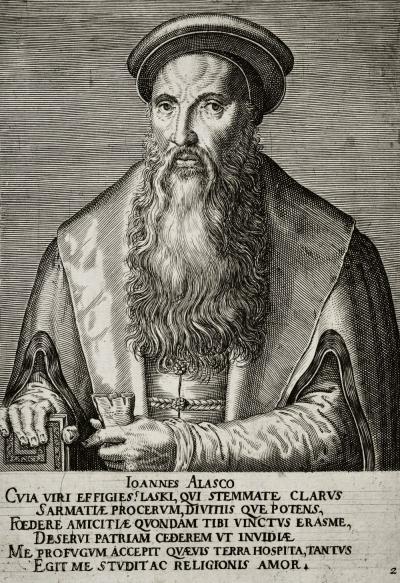

But there were also other reasons to migrate to the West: Merchants from Polish lands, often Jews, sought out the large trading towns and fairs in Breslau or Leipzig; some from Danzig, often Germans, carried out their business throughout half of Europe. Moreover, the Jewish communities in the Old Empire maintained close contact with the much livelier Jewish centres in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Many centres of European learning were also to be found in German lands, which is why large numbers of Polish students found their way to Cologne, Heidelberg, Leipzig or Königsberg. Many academics from Poland stayed in the Empire, for instance Matthäus from Kraków, who was Bishop of Worms from 1405 to 1410, or Johannes a Lasco, who established the Protestant church in East Frisia in the 1540s. A highpoint of the migration of the Polish elite was when August II and August III from the Saxon Wettin dynasty were on the Polish throne between 1697 and 1763 and Dresden attracted the nobility, officers, statesmen and artists from Poland. Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, who grew up in Hoyerswerda, became famous as one of Napoleon’s generals.

Worth mentioning are two settlement areas of Polish-speaking populations in regions that later belonged to the German Empire or to Prussia: The Masurians in southern Prussia, who had migrated to there from Mazovia since the 14th century, and the Polish population in Silesia, who were predominantly able to establish themselves in a large part of Upper Silesia.

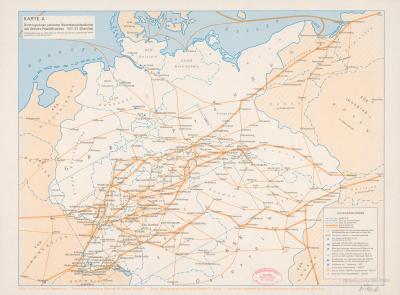

Migratory borders

The situation changed with the three partitions of Poland between 1772 and 1795 because now the borders were moving and not the people. Around 1800, about 2.5 million Polish-speaking people were living in Prussia which stretched all the way to Warsaw. After the Napoleonic wars, the borders were redrawn at the Congress of Vienna, but large old Polish regions still belonged to Prussia. Before the First World War, between 2.5 and 4.5 million Polish-speaking people are thought to have lived in the Empire – it is not known exactly because the statistics are unreliable and many Poles renounced their mother tongue during censuses for fear of discrimination. The Polish settlement centres were West Prussia/Pomerelia, the Province of Poznań/Greater Poland, southern East Prussia and Upper Silesia. Whilst Protestant Masurians succumbed to advancing assimilation, which even before the Second World War was far from complete, Greater Poland in particular developed as a cultural and economic centre of the Polish minority who untiringly pursued cultural autonomy and their own state.

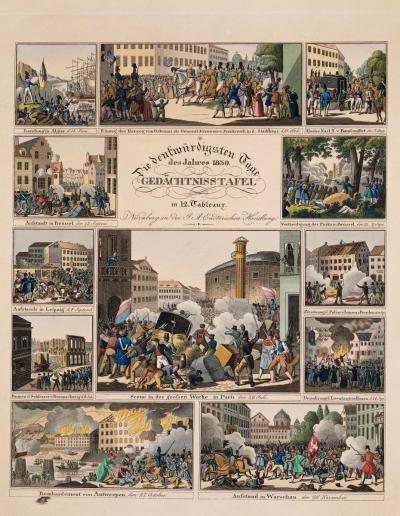

The Pole’s love of freedom was contagious: In 1832, when several thousand Polish officers moved through the German lands to exile in France after they had lost the uprising against Russia, they were greeted along the way by the citizens of German towns cheering them along. And at the Hambach Festival in 1832, their fight against restoration and autocracy was a wake-up call for liberal Europe. Until 1848, when the freedom fighter Ludwik Mierosławski was freed from jail in Berlin-Moabit at the beginning of the March Revolution, the enthusiasm for Poland continued until it came to a debate in the Paul’s Church Parliament in Frankfurt: Shouldn’t a democratic Germany be prepared to return the Polish provinces of Prussia to a free Poland? But how quickly opinions changed: The prospect of the creation of a German national state left the Poles in the German lands as representatives of what appeared to be an increasingly dangerous irredenta. Attempts made by the Prussian government to combat the “Polish danger” as it was increasingly seen, led to numerous confrontations and to the growing discrimination of the Polish section of the population.

Looking for work

The German Empire founded in 1871 offered its citizens equality of legal status, legal protection and free mobility within the borders of the Empire. Prussian Poland also made use of this: The influx of Polish-speaking citizens of the Empire into the industrial regions and mines of the Ruhrgebiet in the decades before the First World War – around 500,000 people – was, to that point, the largest compact migration of a non-German population in German history; it paved the way, so to speak, for all the economic migration that would later follow. But they were also migrating in a time in which, in the eyes of the nationalist parties and of some of the public, Poles, who were becoming the greatest enemies of the Empire, appeared to endanger the unity of the young country through their own national ambitions.

This mixture of cultural closeness and latent discrimination often resulted in Poles shying away from putting their Polish identity on show in predominantly German-speaking regions. Better not to speak Polish on the street, better not be conspicuous, better to quickly integrate into German society. The majority of children born to internal migrants learnt hardly any Polish. At the same time, these migrants were shaped not only by the Ruhr area society (in 1910 for example they represented a quarter of the population in Recklinghausen), but also by other emerging industrial centres, such as the large North German cities or Berlin. However, this group was in no way homogeneous: As well as the Catholic migrants, there was also a large migration of Protestant Masurians, particularly in Westphalia and, as well as the people from Poznań who spoke High Polish, Upper Silesians and Kashubians, with their characteristic dialects and languages, also moved there. The “Ruhr Poles” (westfalczycy), in particular, developed a rich life centred around clubs and associations, and Polish church structures, trade unions and political representation all sprang up.

In addition to the internal Polish migrants, Poles from abroad, from Austrian Galicia or from the regions annexed by Russia also arrived. At times, there were several hundred thousand of them working primarily as seasonal workers in farming, the so-called “Sachsengänger”.

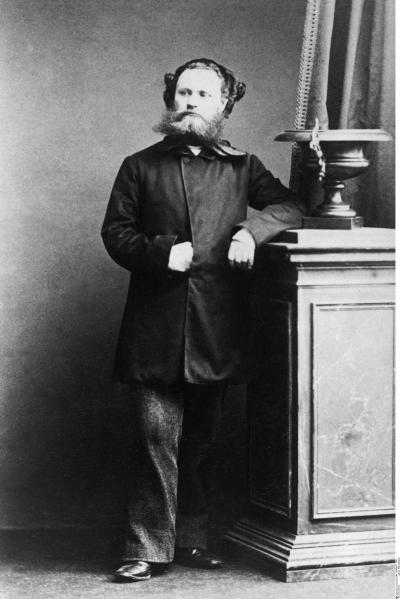

Whilst this was almost exclusively a proletarian economic migration, representatives of the Polish elite also moved to Germany: As the capital, Berlin attracted representatives of the nobility (such as the Radziwiłł and Raczyński families), but Poles also had seats in the Reichstag and in the Prussian state parliament. At times, writers such as Adam Mickiewicz and Józef Ignacy Kraszewski chose to live in Dresden and students moved to the various universities of the Empire; some also had an academic career here. Not least, politicians in the Empire found a place to stay; the socialists Rosa Luxemburg and Julian Marchlewski were just two of many.

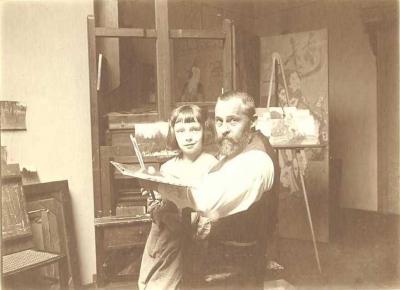

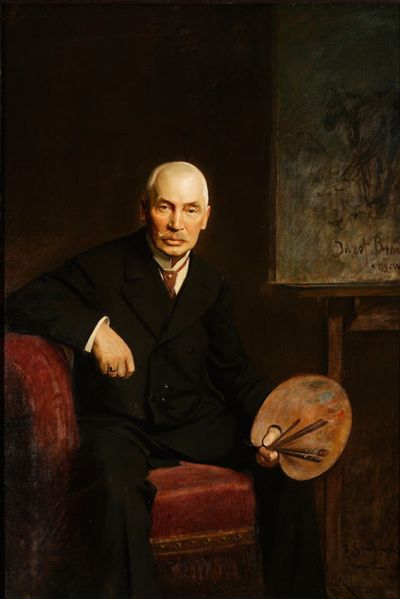

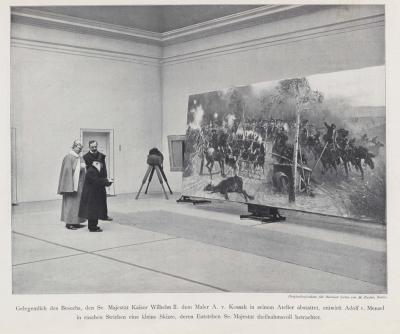

The “Munich School” was particularly well known in Poland. This term conceals the fact that between 1828 and the outbreak of the First World War more than three hundred Polish painters and sculptors were studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and in its surrounds. Even if this was not a “school” in the true sense of the word, various contacts and references developed among the many prominent painters, such as Józef Brandt, Jan Matejko, Aleksander Gierymski, Maksymilian Gierymski, Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski and Wojciech Kossak. In his role as court painter, Kossak is said to have later played an important role in the capital’s art scene. Female artists, such as Olga Boznańska, were also able to improve their skills in Munich, even if there were few females there as women were not allowed to study at the Munich Academy before 1920.

Forced migration: The period of the world wars

Whilst, to this point, Poles had migrated voluntarily or had felt compelled to migrate at most out of economic necessity, the First World War was a turning point: By the end of the war, more than half a million Poles living abroad were recruited for the economy in the Empire, increasingly through coercion as well. Sometimes they also fled from the events of war or, as was the case with Polish Jews, for fear of anti-semitic riots. Directly after the war, there were around 3,500 “East European Jews” in Frankfurt am Main, who for the most part stayed here initially, as was the case in other parts of Germany. Often, however, their mother tongue was not Polish but Yiddish; some spoke German or Russian better.

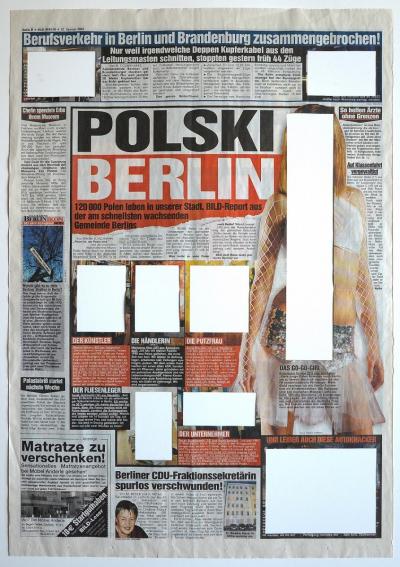

As a result of new borders being drawn in the wake of the Treaty of Versailles and some referenda that followed, Germany lost a large part of the Polish settlement areas in the East. At the same time, because some of the Polish economic migrants from the Ruhr area and from other places were migrating back to an independent Poland or were looking for work in other countries, the number of Polish-speaking residents fell quickly. In the 1920s, there must have been around 1.5 million Polish-speaking people and this number continued to fall until 1939, particularly as a result of the gradual assimilation to the German majority of the population, which was later enforced by the Third Reich. There were now hardly any centres of Polish life left in Germany; but Berlin, Westphalia and western Upper Silesia still had a considerable group of people who were prepared to stand up for Polish issues. Generally speaking, because of the poisonous atmosphere between Germany and Poland, many Poles preferred to make themselves “invisible” and not stand out in German society. The “Union of Poles in Germany”, which was founded in 1922, was unable to stop this development. Incidentally, Poles only had minority status in the part of Upper Silesia that had remained German, and they only had that until 1937.

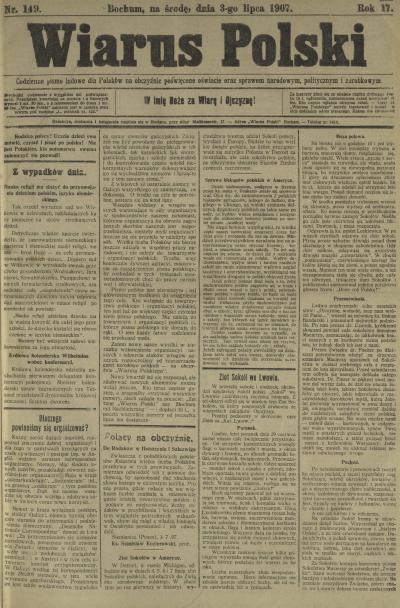

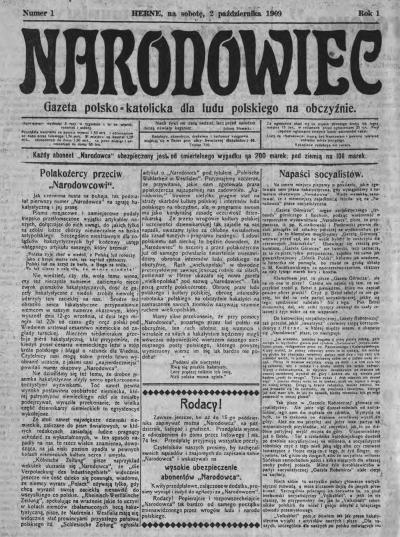

Poles living in the Empire had several press bodies which, however, suffered considerable financial difficulties. For this reason, “Wiarus Polski”, which had been published in Bochum since 1890, moved its head office to the industrial region of northern France which had a large-scale Polish migration, and “Narodowiec”, which had been published in Herne since 1909, followed in 1924. This meant that the only daily newspaper remaining was the “Dziennik Berliński”, which was founded in Berlin in 1897 and which existed with the support of the “Union of Poles” until war broke out in 1939.

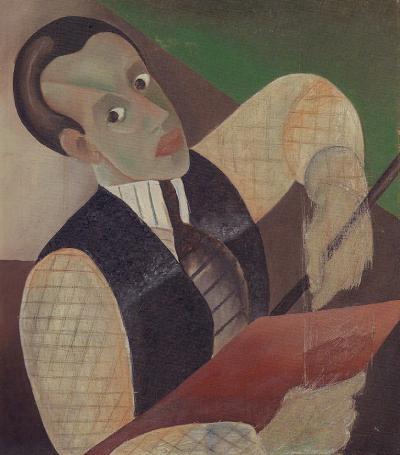

But Poles did not disappear from public life in Germany completely: The film stars Pola Negri and Jan Kiepura enjoyed great success. And Polish Jews also played an important role in music culture and in the entertainment industry, like the band leader Marek Weber. And if you search a little further, you come across a large number of virtually forgotten traces of people. Such as the Bauhaus student Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum or the photographer Stefan Arczyński.

However, this German-Polish-Jewish symbiosis was destroyed by the Nazis: At the end of October 1938, they deported all Polish citizens of Jewish origin to Poland; around 17,000 people were thrown out of their houses overnight. This was a “prelude to the extermination” which was to start soon after.

The Second World War turned Europe on its head. The senior-level representatives of Poland that lived in the Empire were persecuted and some were murdered in concentration camps. A large proportion of conquered Poland was joined to the Empire, the Polish people – Jews and non-Jews – were persecuted, enslaved, expelled and exterminated. Depending on the region, many Poles were forced to sign the “German People’s List”, many young men were then conscripted to the Wehrmacht. Polish officers who were prisoners of war spent the war in camps, simple soldiers were used as forced labour. Around 2.8 million Poles worked for varying lengths of time as forced labourers in industry or agriculture, sometimes under inhuman conditions. Hundreds of thousands were taken to the concentration camps; Jewish Poles were often taken directly to the extermination camps.

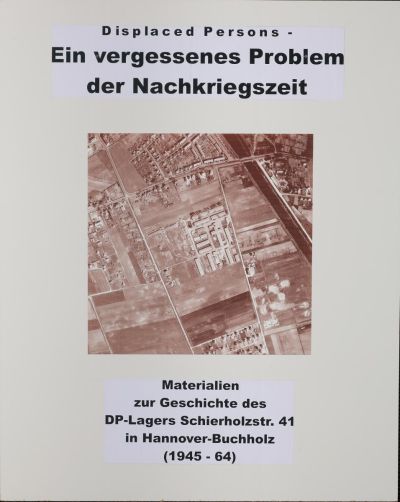

After the War: Poles in Germany – some figures

Directly after the end of the Second World War, there were more than 1.7 million Poles, former forced labourers, concentration camp prisoners and prisoners of war. As displaced persons, they spent months or even years mainly in the western zones and even after most of them had either returned to their homeland or had migrated further afield, there were still around 80,000 of them in the Federal Republic. The attempt to set up Polish territorial structures in Emsland by establishing the town of Maczków ended with the dissolution of the Polish army unit which had carried out their occupation service there. Amongst these dispersed Poles in Germany was a number of illustrious personalities, who were to shape cultural life for decades: They included Artur Brauner, who settled as a Polish Jew in Berlin directly after the end of the war and was to become one of the most important film moguls of the German economic miracle.

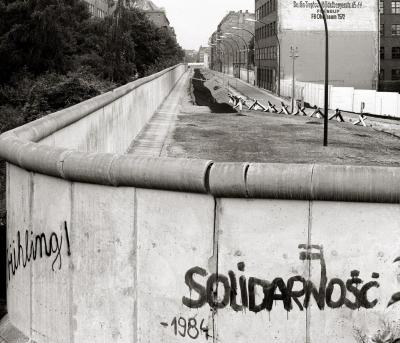

But the number of Polish-speaking people in German soon increased again. Between 1950 and 1990, around 1.4 million persons with German ancestry relocated from the Polish state to the Federal Republic of Germany (others went to the GDR), the majority came over in the 1980s: 520,000 made the move between 1988 and 1990 alone. Whilst, emigrants were initially socialised in German and spoke German in their families, in the 1980s most of them were socialised in Polish and didn’t speak any German, but they did use the legal possibilities to be able to leave Poland in light of the economically and politically difficult situation in the country.

Since the visa requirement was lifted in 1990 and the ability to take on work in Germany gradually became easier, there is now a large number of Polish citizens living in Germany. In 1990 there were 241,000 Poles with only Polish citizenship living in the unified Germany, but at the end of 2018 there were around 860,000. But this is not the whole truth. If you were to ask these people about their migrant background, then you would find that in 2017 2.1 million people with biographical association with Poland were living in Germany; this was the second-largest group after people from Turkey and before those from the Russian Federation. At the same time, the seasonal migration of the Polish labour force persisted, but since Poland entered the EU this number has fallen rapidly.

Integration or separation?

After the Second World War, the cultural patterns of behaviour of the Polish migrants in Germany continued. Such was already the case for many emigrants: Anyone who was more Pole than German tried to find a way into German affluent society as quickly as possible after moving from Poland so that as Poles they could become largely invisible. For large sections of the German post-war society, Poland was seen as an unattractive country, its culture regarded as “inferior”. This belief that there was a cultural gap also had an impact on the migrants from Poland. Only a few actively held on to their native culture, getting involved in Polish associations or clubs. But for the majority, integration, success in the labour market and their children’s future were the number one priority.

This was also the reason why the Poles who had migrated to Germany were hardly identifiable in public as a closed group, particularly because outwardly they did not differ from the “average German”. Even the religious practices of the Poles fitted into the confessional landscape of Germany. Various indicators are testimony to their comparatively good integration in Germany. Compared to migrants from other countries, they are characterised by their low at-risk-of-poverty rate and higher average incomes, by good educational qualifications and a relatively high employment rate.

And whilst some Polish organisations were indeed founded in 1945 immediately after the war, even today Polish migrants are reticent to set up associations and clubs. Even the various umbrella associations have only very minor significance; what works more is the network of the Polish Catholic missions. Some towns have Polish associations which are usually quite small and which are concerned with teaching Polish children the language or promoting cultural matters. They usually work within the Polish community, sometimes they also succeed in reaching a larger public, mostly in the Ruhr area and in Berlin. Berlin as a whole differs significantly from the rest of the Republic: This is where, only 80 kilometres from the Polish border, not just labour migrants but also thousands of Poles, who are culturally active or who simply want to enjoy alternative lifestyles, have been gathering since the 1980s. Today, this has made the town an important centre for Polish culture, or more accurately, a centre for the cultural activities of people from Poland. This is because those people who have migrated from Poland or cultural mavens and intellectuals who have one leg here and the other there no longer subscribe to one nation, but see themselves instead as part of transnational communities, as world citizens or Europeans.

This trend is countered by associations who, even in Germany, want the world to experience Poland’s conservative nature. In some large cities “Klubs der Gazeta Polska” have been established that cultivate a Catholic national conservative world view. Ultimately, there is a range of ideologically neutral associations, for instance a growing number of Polish sports clubs, such as the football club FC Polonia Berlin, FC Polonia Wuppertal, SV Polonia Monachium or KS Polonia Braunschweig.

Today, almost every large German town and many regions have Polish Facebook groups in which sometimes hundreds and sometimes tens of thousands of people catch up on the important things of everyday life. The Polish community can draw upon a now well established ethnic economy providing Polish-speaking services, from doctors to lawyers, from nail studios to wedding chapels. And the more extensive this infrastructure becomes, the more visible it becomes as well. The times in which Poles simply wanted to hide from the majority society are largely consigned to the past now.

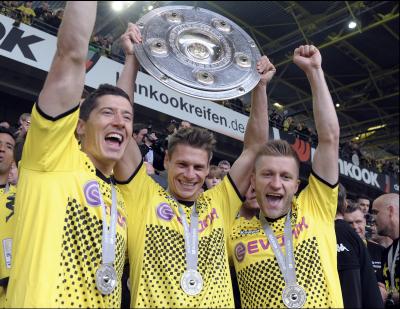

This has also been helped by the slowly growing number of people in public life with a recognisably Polish background. And today it is by no means just a couple of footballers, like Miroslav Klose and Lukas Podolski, or a few personalities from the world of culture whose “foreign” way of speaking, like that of Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who reminded Germans for decades just how closely Germany was intertwined with eastern Europe.

Today things are a bit different: The General Secretary of the CDU, Paul Ziemiak, came to Germany as a child, as did the actress Patrycia Ziółkowska, who uses all the special Polish characters in her name, something the earlier migrant generations liked to refrain from doing, the tennis player Angelique Kerber is committed to her Polish heritage as is the singer Mark Forster, who was born in the Palatinate as the son of a Polish mother and who surprised German television viewers with a Christmas carol sung in Polish. Margarete Stokowski is shaping the feminist debate in the country; Henryk M. Broder is still stirring up a journalistic storm with his recalcitrant commentaries, and the “Zeit” journalist Alice Bota makes a significant contribution to the presence of Poles in Germany. In German universities and in symphony orchestras, in large IT companies and in the media industry – everywhere today there are people who feel a biographical association with Poland.

Summary: The road to visibility

For Poles living in Germany it is much the same as for most migrant groups around the world: Some of them will always remain invisible, will want to quickly leave their heritage behind them or at least not demonstrate it in public, preferring instead to integrate quickly into the surrounding majority society. Others see their role as being to demonstratively hold on tight to their heritage whilst in emigration and to show this heritage to non-Polish fellow human beings as well. Many choose one of the numerous ways in between, these are European ways: Consciously living with several identities, one German, one Polish, perhaps one that’s Upper Silesian or Bavarian as well, and recognising this variety of individual identities as a richness in their lives. The cultural closeness of Poles and Germans means that it is even easier to confidently advocate Polishness together with Germanness, even if there will always be people who try to highlight the supposed incompatibility. But just how great are the differences between sauerkraut and kapusta kiszona, between bratwurst and krakowska, between cheesecake and sernik really? It is precisely this closeness that results in the most successful roads to visibility, building bridges and generating understanding.

Peter Oliver Loew, April 2020

Peter Oliver Loew, Historian, Director of the German Poland Institute, honorary professor at Darmstadt Technical University. His areas of interest include German-Polish relationships past and present, Poles in Germany, Danzig, aspects of literature and music.

Publications on this subject include:

Peter Oliver Loew: Wir Unsichtbaren. Geschichte der Polen in Deutschland. München: C.H. Beck 2014.

Peter Oliver Loew. My niewidzialni. Historia Polaków w Niemczech. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego 2017.

(Published together with Dieter Bingen, Andrzej Kaluza, Basil Kerski): Polnische Spuren in Deutschland. Ein Lesebuchlexikon. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 2018.

(Publ.): Lebenspfade. Polnische Spuren in RheinMain. Darmstadt: Deutsches Polen-Institut 2019

Auswahl weiterer Beiträge auf unserem Portal:

Künstlerinnen und Künstler

Helena Bohle-Szacki, jüdisch-polnische Modedesignerin der Nachkriegszeit und Zeitzeugin der NS-Zwangsarbeit, *1928 in Białystok, †2011 in Berlin.

Karol Broniatowski, polnischer Bildhauer, *1945 in Łódź, lebt in Berlin.

Monika Czosnowska, Fotografin, *1977 in Szczecin/Stettin, lebt in Berlin.

Jeremias Falck, bedeutender Kupferstecher, *1610 oder 1619 in Danzig, †1664 in Hamburg.

Małgosia Jankowska, polnische Malerin, *1978 in Sochaczew, lebt in Berlin.

Danuta Karsten, polnische Künstlerin, *1963 in Mała Słońca, lebt in Recklinghausen und Herne.

Marta Klonowska, polnische Künstlerin und Glasmacherin, *1964 in Warschau, lebt in Düsseldorf und Warschau.

Agata Madejska, polnische Künstlerin, *1979 in Warschau, lebt in London.

Roland Schefferski, deutsch-polnischer Objekt- und Installationskünstler, *1956 in Katowice, lebt in Berlin.

Karina Smigla-Bobinski, deutsch-polnische Intermedia-Künstlerin, *1967 in Szczecin/Stettin, lebt in München.

Marian Stefanowski, deutsch-polnischer Fotograf, lebt in Berlin.

Stefan Szczygieł, deutsch-polnischer Künstler und Fotograf, *1961 in Warschau, †2011 ebenda.

Stanisław Toegel, Zeitzeuge der NS-Zwangsarbeit und international bekannter Karikaturist, *1905 in Jaworów (heute Jaworiw), †1953 in Bytom.

Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański, polnischer Bildhauer und Vertreter der Konkreten Kunst, *1950 in Gdańsk/Danzig, lebt in Hamburg.

Literatur- und Kulturschaffende

Artur Brauner, polnisch-jüdischer Filmproduzent, *1918 in Łódź, †2019 in Berlin.

Brygida Helbig, eigentlich Dr. Brigitta Helbig-Mischewski, Pseudonym Anna Maria Birkenwald), deutsch-polnische Schriftstellerin, *1963 in Szczecin/Stettin, lebt in Berlin.

Pola Negri (eigentlich Apolonia Chalupec, auch Barbara Apolonia Chałupiec), polnische Schauspielerin und großer Star des Stummfilms, *1897 in Lipno, Russisches Kaiserreich, †1987 in San Antonio, USA.

Anna Piasecka, deutsch-polnische Schriftstellerin, *1981 in Słupsk, lebt in der Nähe von Münster (Westfalen).

Marcel Reich-Ranicki, deutsch-polnischer Autor und Publizist, *1920 in Włocławek; †2013 in Frankfurt am Main.

Emilia Smechowski, polnisch-deutsche Journalistin und Schriftstellerin, *1983 in Wejherowo, lebt in Berlin.

Roma Stacherska-Jung, polnisch-deutsche Journalistin und Radio-Moderatorin.

Margarete Stokowski, polnisch-deutsche Autorin und Kolumnistin, *1986 in Zabrze, lebt in Berlin.

Janina Szarek, polnische Regisseurin, Schauspielerin, Theaterpädagogin, Intendantin und Leiterin einer Schauspielschule, *1946 in Ruda Różaniecka, lebt in Berlin.

Sonja Ziemann und Marek Hłasko, deutsche Schauspielerin und polnischer Schriftsteller, wohl bekannteste deutsch-polnische Ehepaar der Nachkriegszeit.

Musikerinnen und Musiker sowie Komponisten

Thomas Godoj (Tomasz Jacek Godoj), polnisch-deutscher Rocksänger und Songwriter, *1978 in Rybnik.

Mark Forster (eigentlich Mark Ćwiertnia), deutscher Pop-Sänger und Songwriter, Sohn einer polnischen Mutter und eines deutschen Vaters, *1983 in Kaiserslautern.

Margaux Kier, deutsch-polnische Sängerin und Schauspielerin, *in Bydgoszcz, lebt in Köln.

Krzysztof Meyer, polnischer Komponist, Pianist, Musiktheoretiker und Hochschullehrer, *1943 in Krakau, seit 1987 wohnhaft in Deutschland.

Katarzyna Myćka, international renommierte polnische Marimba- und Schlagzeug- Musikerin, *1972 in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, lebt in Stuttgart.

Vitold Rek, polnischer Kontrabassist und Komponist des Creative Jazz, *1955 in Rzeszów, lebt im Rhein-Main-Gebiet.

Janusz Maria Stefański, bedeutender Musiker und führender polnischer Jazz-Schlagzeuger, *1946 in Krakau, †2016 in Frankfurt am Main.

Lech Wieleba, polnischer Kontrabassist und Komponist.

Leszek Żądło, polnischer Jazzmusiker, *1945 in Krakau.

Wissenschaftler

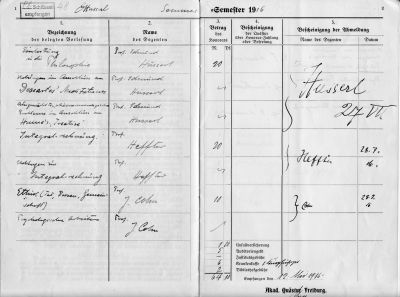

Roman Witold Ingarden, polnischer Philosoph und Phänomenologe, *1893 in Krakau, †1970 ebenda.

Jan Łukasiewicz, polnischer Philosoph, Mathematiker und Logiker, *1878 in Lemberg (Lwów), †1956 in Dublin.

Unternehmer

Wojtek Grabianowski, Architekt, *1944 in Posen, lebt in Düsseldorf.

Tomasz Niewodniczański, Kernphysiker, Sammler und Unternehmer, *1933 in Wilna, †2010 in Bitburg.

Zeitgeistpersönlichkeiten

Susanna Fels, Künstlerin, Fotografin und enge Begleiterin von Witold Gombrowicz, *1937 in Breslau, lebt in Berlin.

Anatol Gotfryd, Literat, Kunstliebhaber und Künstlerfreund, *1930 in Jablonow, lebt in Berlin.

Rosa Luxemburg, einflussreiche Vertreterin der europäischen Arbeiterbewegung, des Marxismus, Antimilitarismus und „proletarischen Internationalismus“, *1871 in Zamość, †1919 in Berlin.

Stanisław Mikołajczyk, polnischer Politiker, Ministerpräsident der polnischen Exilregierung während des Zweiten Weltkriegs und Vizepremier Polens nach Kriegsende, *1901 in Holsterhausen (heute Herne), †1966 in Washington.

Zdzisław Nardelli, polnischer Radioregisseur, Schriftsteller und Dichter, *1913 in Cieszynie, †2006 in Warschau.

Józef Piłsudski, polnischer Militär, Politiker und Staatsmann, Marschall der Zweiten Polnischen Republik, *1867 in Zułowo bei Wilna, †1935 in Warschau.

Stanisław Przybyszewski, polnischer Schriftsteller, *1868 in Lojewo, †1927 in Jaronty.

Antoni Graf Sobański, Antoni Graf Sobański, *1898 in Obodówka, †1941 in London.

Ewa Maria Slaska, Journalistin, Schriftstellerin und Oppositionelle, *1949 in Sopocie, lebt in Berlin.

Adam Szymczyk, polnischer Kunstkritiker und Kurator, von 2003 bis 2004 Direktor und leitender Kurator der Kunsthalle Basel, 2017 künstlerischer Leiter der Documenta 14 in Kassel und Athen, *1970 in Piotrków Trybunalski.

Andrzej Wirth, polnisch-US-Amerikanischer Theaterwissenschaftler, Theaterkritiker und Hochschullehrer, *1927 in Włodawa; †2019 in Berlin.

Institutionen

Club der Polnischen Versager, Institution des deutsch-polnischen Kulturaustauschs in Berlin, seit 2001.

Polnisches Theater Kiel, seit 1982.

Radio Cosmo, seit 1994.

Zeitungen

Wiarus Polski, polnischsprachige Tageszeitung mit der höchsten Auflage im Ruhrgebiet, 1890 bis 1923 in Bochum erschienen, 1923 bis 1961 (mit Unterbrechungen) in Frankreich.

Narodowiec, polnischsprachige Zeitung im Ruhrgebiet, 1909 bis 1924 in Herne erschienen, 1924 bis 1989 in Lens/Frankreich.

Dziennik Berliński, polnischsprachige Tageszeitung in Berlin, 1897 bis 1939 in Berlin erschienen.

Ereignisse, Konzerte und Ausstellungen

Der erste Kongress der Polen in Deutschland, 6. März 1938 in Berlin, größte Zusammenkunft der Polen in Deutschland während der NS-Zeit.

Deutsch-polnische Canaletto-Ausstellung in Dresden, Warschau und Essen 1963-1966, Ausstellung der Gemälde des Barockmalers Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto (1722-1780)und zugleich erstes gemeinsam durchgeführtes kulturelles Ereignis der beiden „sozialistischen Bruderländer“ DDR und Volksrepublik Polen.

Lukas-Passion von Krzysztof Penderecki im St. Paulus Dom zu Münster, Krzysztof Penderecki stellt am 30. März 1966 sein epochalen Werk "Lukas-Passion", eine Auftragsarbeit des Westdeutschen Rundfunks, im Münsteraner Dom vor.

Generationsübergreifend – Polnische Kunst in Marl 6. März bis 12. Juni 2016, die Ausstellung in Marl gruppierte sich um einen Kern von Werken polnischer Kunst aus der Sammlung von Werner Jerke.

Frömmigkeit und Nachtgesichte – Naive Kunst aus Polen im Spiegel der Moderne, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen zeigte 2016 ihren umfangreichen Bestand von Exponaten aus Polen.

„Malerfürst“ Jan Matejko in der Bundeskunsthalle, im Rahmen der Ausstellung „Malerfürsten“ zeigte die Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn vom 29.9.2018 bis 27.1.2019 58 Werke und kulturhistorische Objekte zu dem polnischen Historien- und Porträtmaler Jan Matejko (1838-1893).